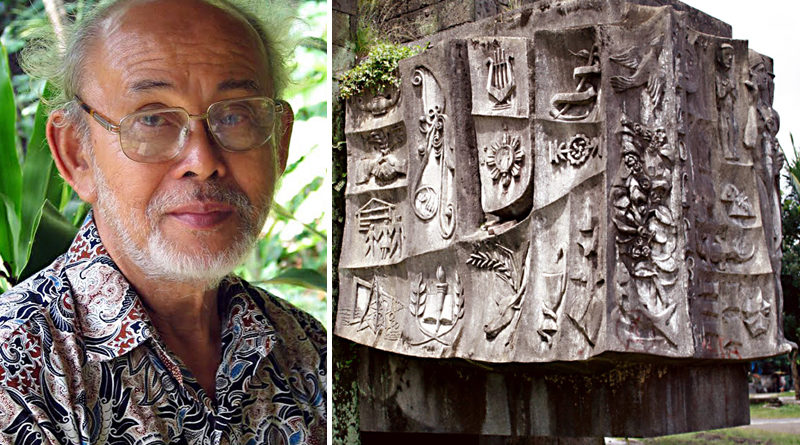

ASEAN ARTS: SCULPTURE – Napoleon Abueva, father of modern Philippine sculpture, 88

National Artist Napoleon Abueva’s work is scattered across the University of the Philippines campus in Diliman, including the 1966-67 concrete sculptures ‘Tribute to Higher Education’ on University Avenue (above).

MANILA, Philippines — Napoleon Isabelo Abueva, whose contribution to Philippine visual arts spans more than six decades and is characterized by his unceasing curiosity of sculptural material and innovation of form, died yesterday after a lingering illness. He was 88.

For many Filipino artists working today, Abueva (known as “Billy” to family and friends), dared them to think beyond the usual medium of stone, wood and metal, and apply their full capacity of expression in fluid, evocative shapes that work with – and inevitably transcend – the surrounding space.

“In a generation of innovators consciously or unconsciously contributing their share to the evolving Philippine tradition,” writes Purita Kalaw-Ledesma in the seminal book, The Struggle for Philippine Art, “Abueva was in a class by himself. In sculpture, he was the innovator of the ‘50s.”

Abueva single-handedly brought the medium of sculpture, which was then lagging behind painting, in step with modernism. No material was spared from his transformative touch. Narra, bamboo, coral, alabaster, brass and stainless steel – sometimes in combinations thereof – yielded to the power of his hands and his instruments. Ranging from figurative to geometric to minimalist forms, from secular to religious imagery, his works embody an inner creative order that is close to divine.

In 1976, at the age of 46, he received the National Artist recognition – the youngest artist so honored. Two years later, he served as dean of the College of Fine Arts, University of the Philippines in Diliman, inspiring succeeding generations of sculptors. Both for his body of work and influence, Abueva is rightfully called the Father of Modern Philippine Sculpture.

Born on Jan. 26, 1930, Abueva early on showed a knack for sculpting things. His daughter, Amihan Abueva, tells the filmmaker Katrina Ventura in a documentary released by the UP Diliman Office for Initiatives in Culture and the Arts (OICA): “The family legend is he started to be interested in sculpture when he was a kid. Because my family lived in Bohol and we had a farm and my dad liked to play in the mud… So when his sisters would make mud pies like bibingka, he would make dogs, carabaos and so on from the mud.”

Prone to misbehaving, Abueva was called Napoleon by a Belgian nun who, of course, alluded to Napoleon Bonaparte. The young Billy liked it. Calling himself Napoleon seemed like destiny as the namesake emperor once said, “If I weren’t a conqueror, I would wish to be a sculptor.”

When the second World War broke out, the Abuevas moved to Duero, Davao. Because his parents, Teodoro and Purificacion, were part of the resistance, they were killed by the Japanese. Billy, then a teen-ager, was tortured.

It was at UP Diliman when Abueva decided to become a sculptor. He studied under Guillermo Tolentino, an avowed classicist who believed in the harmony of expression of sculptural forms. His exposure as a Smith-Mundt and Fulbright scholar at Cranbook Academy of Art and his stint at Harvard University in the United States encouraged Abueva to move out of the shadow of his mentor and foster a modernist idiom.

Easygoing teacher

As a professor at UP Diliman, Abueva had an easygoing approach in the classroom. One of his students, Leo Abaya, tells Ventura: “Abueva, when he was my teacher, impressed me more like he was a father-figure more than a teacher. In fact, there was little difference between him in the classroom and him outside. Because when we were in his class, we did not only hold classes in the classroom, he would invite us to his place and then the group we had – the class – would have lunch.”

As a long-time professor in the institution, Abueva has works scattered across campus, including the UP Gateway (1967) and the Nine Muses (1994) located across the UP Faculty Center. His other major works include Kaganapan (1953), Kiss of Judas (1955), The Transfiguration, Eternal Garden Memorial Park (1979), Sunburst at The Peninsula Manila hotel, the bronze figure of Teodoro Kalaw in front of the National Library and murals in marble at the National Heroes Shrine, Mt. Samat, Bataan.

His “Sandugo” (Blood Compact Shrine) in Tagbilaran City, Bohol is also a landmark as it is in honor of the site of the first international treaty of friendship between Spaniards and Filipinos.

In the depiction of women in his works, Amihan mentions in the documentary that “he liked women who had powerful bodies… If you look at the Nine Muses, these are all women with muscle, women who were powerful. I think he grew up with a lot of strong women: his mother, his grandmother, his sisters. My mom is also a strong woman. I think that’s what he appreciated.”

In his 88 years, Abueva suffered several strokes, starting in 1985. A major one in 2012 necessitated an operation. “And this was when I realized,” Amihan reveals in the documentary, “that there were so many people who loved my dad. Because we had such a small family, there were only two of us who could donate blood – my son and myself. And we needed almost 40 bags of blood to replenish what had been used during the operation. So I had no other choice but to make a post in Facebook about this… More than 70 people came to the hospital. Those who were too old to donate blood or were having health difficulties of their own… would actually send their children or grandchildren to come and donate blood.”

In 2014, another stroke hit Abueva which he miraculously survived. Late last year, Abueva had a bout with pneumonia, leading to more health complications.

Abueva is survived by his wife Cherry and his children Amihan, Mulawin and Duero; his sisters Amelia and Teresita; his brothers Antonio and Jose, who once served as the president of UP Diliman.

“Abueva’s story,” writes Kalaw-Ledesma, “is that of a man constantly seeking to discover himself through his art.”

At a later stage of his career, art led Abueva to see anew the beauty of creation that he so passionately represented in his sculptures. “Sometimes,” he said, “I don’t know which is of greater importance, the sculpture or the subject. The ends and means are one and the same.”

The wake for Abueva began last night at Delaney Hall, UP Parish of the Holy Sacrifice in Diliman. Details of interment and National Artist honors will be announced later.

NCCA, Palace condole

The National Commission for Culture and the Arts expressed condolences to the Abueva family.

“We are all deeply touched by his genius, and Abueva remains immortal in the Filipinos’ heart and soul,” the NCCA said in a statement yesterday.

“As the nation celebrates National Arts Month, we also celebrate the life and works of Abueva, whose legacy enriched us and will continue to enrich and inspire us as a people as well as the whole world,” it added.

Malacañang yesterday expressed sadness over the death of Abueva, calling him “a renowned virtuoso whom future generations of Filipino artists will look up to.”

“The Palace extends its deepest condolences to the family and friends of National Artist Napoleon Abueva. We join the entire nation in mourning the passing of an exemplary artist,” presidential spokesman Harry Roque said in a statement. – Evelyn Macairan, Alexis Romero

NOTE : All photographs, news, editorials, opinions, information, data, others have been taken from the Internet ..aseanews.net | [email protected] | For comments, Email to : Goldenhands Arts Club | [email protected]| Contributor