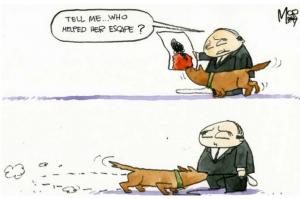

OP-ED EDITORIAL: OPINION & CARTOON – ‘Trump’s tariffs could trigger a trade war’ – Sunday, March 4, 2018

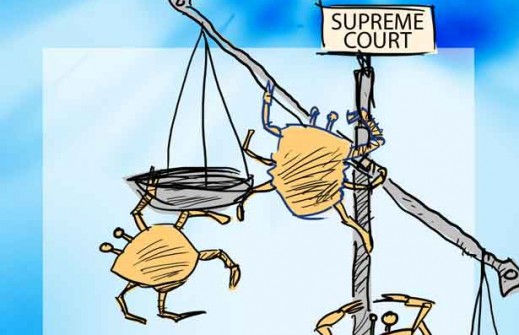

7.1. Travails of a liar – The Daily Tribune

.

.

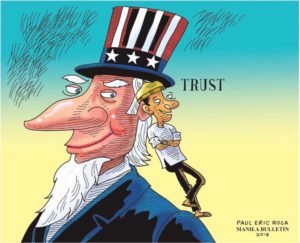

7.2 Nations Filipinos trust the most – The Manila Bulletin

.

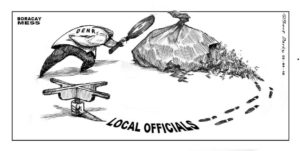

7.3. All too human – The Manila Standard

.

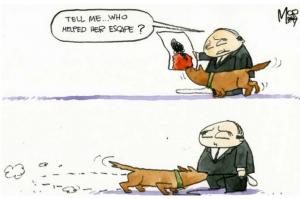

7.4. The “Bathroom” pinay – The Manila Times

.

7.5. Profound challenge for new POC chief – The Philippine Daily Inquirer

7.6. Fire prevention – The Philippine Star

.

7.7. Saudi employers naman ang harapin – Pilipino Star Ngayon

.

.

8.1. To keep or discard family traditions? – For The Sunday Times

Lydia Lim- Associate Opinion Editor

Since joining the paper in 1999, she has covered local politics, policies and Singapore-Malaysia relations, three journalism beats that have taken her around the island and the world, including to international courts in Hamburg and the Hague for two exciting hearings on reclamation and Pedra Branca. In her current day job, she edits the paper’s Opinion pages. She also writes a column in The Sunday Times.–

Since joining the paper in 1999, she has covered local politics, policies and Singapore-Malaysia relations, three journalism beats that have taken her around the island and the world, including to international courts in Hamburg and the Hague for two exciting hearings on reclamation and Pedra Branca. In her current day job, she edits the paper’s Opinion pages. She also writes a column in The Sunday Times.–

..

9.1. Regime’s best-laid plans still subject to folly –

VEERA PRATEEPCHAIKUL FORMER EDITOR

– The Bangkok Post

VEERA PRATEEPCHAIKUL FORMER EDITOR

– The Bangkok Post

100.1 Going away to celebrate a Tết homecoming – Trịnh Lập – Viet Nam News

.

NOTE : All photographs, news, editorials, opinions, information, data, others have been taken from the Internet ..aseanews.net | [email protected] |

.

For comments, Email to :

D’Equalizer | [email protected] | Contributor.