ASIA-BALUKHALI CAMP, COX’S BAZAR, Bangladesh: ROHINGYA – Women find hope amid Rohingya refugee camp dangers

Camp administrators working to combat sexual abuse, violence and exploitation

.

Dressed in a safari vest, cargo pants and combat boots, Mr Shamimul Huq Pavel looks more the part of a military instructor than refugee camp administrator.

He is fed up with seeing Rohingya refugee women single-handedly carrying their babies while hauling heavy food rations home. So he has issued a warning to the men among the 70,000 refugees he oversees: “If any women is seen carrying a big sack and she has a competent male person at her home, that male person would have to answer to me.”

It has been over five months since nearly 700,000 Rohingya Muslims fled an army crackdown in Myanmar to Bangladesh, bearing horrific memories of arson, murder, torture and gang rape.

The hills in southern Cox’s Bazar have been stripped of foliage and packed instead with thousands of bamboo-framed, tarpaulin-lined huts. Aid agencies, working together with the Bangladeshi government, have met the most pressing needs of food, shelter and immediate medical attention.

As the world’s largest refugee settlement takes shape, the authorities in Muslim-majority Bangladesh are grappling with the implications of the Rohingyas’ conservative social order.

Mr Pavel, a senior assistant secretary with the Ministry of Land, has been administering a section of Kutupalong camp for over three months. “I have given all the males a very strong message,” he tells The Sunday Times. “If anything happens unjustly with any girl, any child, any mother, any sister, things might get worse for them.

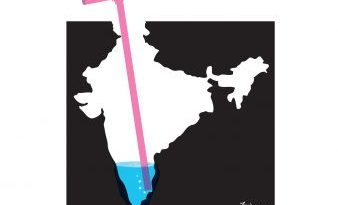

> Number of reported violent incidents – including sexual violence – over the past five months against female refugees.

> The number of refugees who have arrived in Bangladesh from Aug 25, after fleeing an army crackdown in Myanmar

In the dry winter of February, listless men and boys loiter near the dusty roads and bamboo bridges over streams. But there are far fewer young women in sight.

Rural Rohingya girls tend to be taken out of school once they reach puberty, kept away from the public eye, and married not long after. Domestic violence is common.

Thrust into a cheek-by-jowl existence in a refugee camp after living gender segregated lives in Myanmar, the women struggle to maintain the modesty dictated by patriarchal norms.

With women-only latrines and washing spaces scarce and sanitary napkins in short supply, they struggle to keep clean when menstruating, which puts them at higher risk of infection. Many are also reluctant to seek medical aid as there are few female doctors around, says Ms Jahida Begum, a Bangladesh-born Rohingya refugee who spends each day visiting new arrivals.

SPEAKING UP FOR WOMEN

I have given all the males a very strong message. If anything happens unjustly with any girl, any child, any mother, any sister, things might get worse for them.

MR SHAMIMUL HUQ PAVEL, refugee camp administrator.

SAFETY CONCERNS

I want my husband to live with us because I don’t feel safe here. My daughter is becoming a young woman day by day. If my husband is here, people will see that there is a man in the house, they won’t talk bad about her.

MS MUKIMA, who fled Myanmar with her three young children and whose husband lives with his other wife and children.

PICKING UP NEW SKILLSI used to be upset and depressed. I cried a lot. But now I feel more confident.

MS MOHSANA BEGUM, a volunteer recruited to do home visits and investigate camp incidents.

.

According to a Jan 27 update by the Inter Sector Coordination Group, there were 5,572 reported incidents of violence – including sexual violence – over the past five months against the female refugees. The publication highlighted that the “lack of access to basic services and self-reliance opportunities for refugees, especially for women and girls, are increasing the risk of being forced into negative coping mechanisms and exposed to serious protection risks, such as trafficking, exploitation, survival sex, child marriage, and drug abuse”.

Households led by women are particularly vulnerable. Ms Mukima, 35, had to beg to survive after fleeing Myanmar with her three young children. She eventually found enough material to erect a tent in Balukhali camp, where the family of four now live.

Her husband, who is 70 years old, lives with his other wife and children, says Ms Mukima, who goes by one name.”I want my husband to live with us because I don’t feel safe here,” she says, as her two sons aged three and eight, and gangly 11-year-old daughter listen in.

“My daughter is becoming a young woman day by day. If my husband is here, people will see that there is a man in the house, they won’t talk bad about her.”

Ms Mukima also worries about money. She is thinking of marrying her daughter off when she reaches her teens to ease her own financial burden.

Changing attitudes is a slow, mammoth task.

When Ms Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, executive director of the United Nations’ gender equality agency, visited the women-only space in Balukhali on Thursday, she turned cheerleader to teenage girls gathered with their mothers.

“If you marry when you are a child, you are going to be hungry,” she tells them, urging them to aim higher and perhaps even follow her path from her home country of South Africa to New York, where she works as the chief of UN Women.

She tells The Sunday Times she will lobby for more training for the women so that they can earn a living even when they leave the camp.

“Whatever happens to them, whether they go back, whether they stay, they should have something to help them to live.”

Going home is not an option for now. While Myanmar and Bangladesh have inked a repatriation deal, many say conditions within Myanmar – where the majority regard Rohingya as illegal “Bengali” immigrants – remain unsafe. Dhaka maintains that preparations are not complete.

Before that day comes, Mr Pavel is doing his bit to reorder camp life. He has recruited 60 women among the Rohingya refugees to do home visits and investigate camp incidents alongside their male counterparts.

Recently, 20 of these male and female Rohingya volunteers descended upon the home of a refugee who beat up his sister-in-law so badly that she could not walk.

One of the volunteers, Ms Mohsana Begum, says the number of domestic violence cases in her camp has tailed off since the scheme was introduced. The 25-year-old mother of two has also picked up some people management skills. “I used to be upset and depressed. I cried a lot. But now I feel more confident.”

Another camp administrator A. S. M. Obaidullah uses a more offbeat method of dealing with errant husbands. He once ordered a Rohingya man who beat his wife to prepare a meal. The man was stunned but complied. It was the first time he had ever cooked.

“It’s about putting yourself in another person’s shoes,” Mr Obaidullah explains.

The man, he says, did not beat his wife again.

RELATED ARTICLES:

.

Myanmar denies report of mass graves in Rakhine

A Rohingya refugee girl at Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh. Nearly 700,000 people have fled to Bangladesh since last August.ST PHOTO: TAN HUI YEE

COURTESY:

The Straits Times

PUBLISHED FEB 4, 2018, 5:00 AM SGT

Tan Hui Yee- Regional Correspondent in Cox’s Bazar

.

NOTE : All photographs, news, editorials, opinions, information, data, others have been taken from the Internet .. aseanews.net | [email protected] |

For comments, Email to :

Aseanews.Net | [email protected] | Contributor: