OP-ED COLUMNISTS: Thinking Aloud By Chua Mui Hoong ‘Inequality is a threat – name it, and face it’ – The Straits Times

Singapore must not become a society where people feel the system is stacked against them, favouring a minority

.

.

Thirty years ago, as an intern for The Straits Times, I worked on a two-part feature on Children of the Establishment.

It was both an easy and difficult feature to do. I was then studying at Cambridge University on a government scholarship. All I did was talk to my friends and friends of friends. They included offspring of a diplomat, university professor, senior lawyer, doctors, and others in establishment circles. My university mates were, well, just mates. We talked. They were not at all snobbish or arrogant.

But it was also a difficult assignment because I was writing about class, and although I went to college with them, I stood on the other side of the divide, as a child of working-class parents.

I wrote up some interviews and then concluded the series with a short piece on my own reflections. I noted that most of the families knew each other, and most had close friends from the same socio-economic circles.

I wrote that it was reassuring that wealth had not bred decadence, but a sense of responsibility and a strong work ethic. But, I also added: “In a society where eight out of 10 live in Housing Board flats, these people show a disturbing unawareness of the other end of society. Most have little interaction with people from different, less privileged backgrounds.”

Fast forward 30 years, and the issue of the class divide has resurfaced, with a vengeance.

An Institute of Policy Studies survey on social capital put hard numbers to what many Singaporeans have noticed anecdotally and spoken about privately: that despite our aspiration to be a meritocratic society with high social mobility, we may in fact be coming even more class-riven.

The Straits Times report on the survey, published in December, put it starkly in the first sentence: “The sharpest social divisions in Singapore may now be based on class, instead of race or religion.”

The survey asked Singaporeans where they lived, what schools they went to, and who their friends and associates were. It found that those who live in public housing have ties to 4.3 people in public housing and 0.8 people in private.

People who studied in “non-elite” schools had ties to 3.9 people who went to similar schools, and ties to only 0.4 people who studied in “elite” schools.

.

ST ILLUSTRATION: MANNY FRANCISCO

.

What the survey shows is a concentration of social networks around class differentiators such as housing type and schools attended.

It is clear that Singapore’s once egalitarian, easy-going society is stratifying.

.

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong acknowledged this in Parliament this month. Responding to an MP’s question, he said: “The issues of mitigating income inequality, ensuring social mobility and enhancing social integration are critical. If we fail – if widening income inequalities result in a rigid and stratified social system, with each class ignoring the others or pursuing its interests at the expense of others – our politics will turn vicious, our society will fracture and our nation will wither.”

I agree with PM Lee that left unchecked, inequality will turn Singapore’s cohesive politics vicious, fracture our society, and wither our nation. I was glad he didn’t mince his words. It’s time to talk about inequality with the seriousness the issue deserves.

But I think the issue goes beyond income inequality to one of wider social inequalities that are embedded in our system.

This is because inequality is not about absolute deprivation, unlike poverty. When families are poor, a hand up or a handout can help them move into more comfortable lives.

But inequality is a structural impediment. Inequality is about how a society’s policies, structures, assumptions and decisions work together to create advantage for some groups, and obstacles for others.

We can see how politics globally have become fragmented as societies are driven apart by competing interests, and when people feel that the country’s systems are unequal and stacked against them.

.

RELATED STORY

Parliament: Singapore will wither if society is rigid and stratified by class, says PM Lee

Multiple agencies are involved in encouraging integration between classes, such as urban planners designing shared spaces like hawker centres and playgrounds. PHOTO: ST FILE

.

RELATED STORY

Why Singapore gives top priority to fighting income inequality

.

We must not allow that to happen in Singapore.

In Singapore, we have started to tackle income inequality in a concerted manner. As PM Lee and other government leaders have noted, the Gini coefficient that measures income inequality fell from 0.470 in 2006 to 0.458 in 2016, its lowest in a decade. When government taxes and transfers are factored in, the 2016 figure is even lower at 0.402.

Programmes like the Workfare Income Supplement, and transfers to help low-wage workers boost their retirement savings or help them cope with the goods and services tax, all raise income levels at the bottom. As a society, we also continue to have fairly good intergenerational social mobility.

But will it continue to be so?

I got to thinking about this after reading a fascinating new book by sociologist Teo You Yenn, titled This is What Inequality Looks Like.

You Yenn’s book is a mix of ethnography and analysis. She writes about structures of inequality that many of us are oblivious to, drawing on stories of the people she has done research on.

Hers is a gently probing, insistent voice, unpacking assumptions behind common practices and beliefs in Singapore to reveal the unequal structures that sometimes trap people in poverty and insecurity. (I recommend this book be read by every politician and civil servant, especially those involved in administering social policy.)

For example, insisting on housing subsidies being funnelled to married parents leaves out precisely the most vulnerable children – those with unmarried parents who are more likely to be struggling to cope.

Rather than devote more resources to the most vulnerable young, inequality is perpetuated through the generations by denying them housing subsidies given liberally to those from intact families.

What saddens me most in reading the book and the news reports around the IPS survey is the realisation that Singapore society has changed for the worse in the 30 years since I wrote that feature about Children of the Establishment.

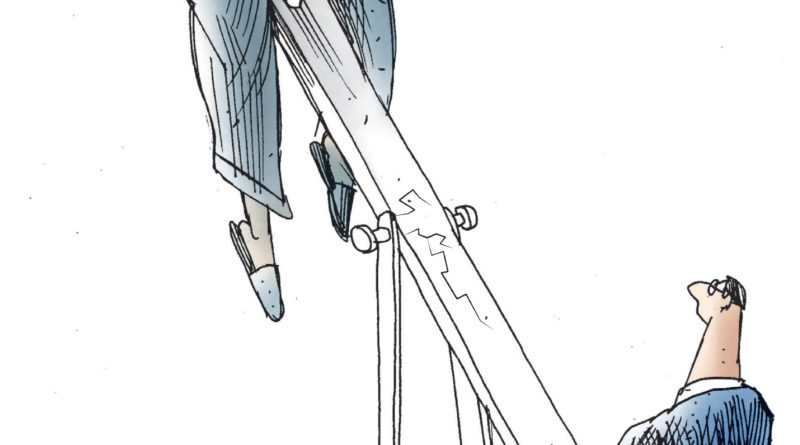

This is especially the case for our education system. Once a conveyor belt for meritocracy, propelling many a taxi driver’s son or hawker’s daughter along a pathway to academic achievement and a well-paying job with good social standing, our education system risks becoming a bastion of privilege, where the powerful and well-connected protect access to the nation’s well-regarded primary schools for their own kind.

And with the complicated through-train system, getting into the “right” primary school can secure your secondary school education – and as we know now from the IPS survey – even a lifetime of access to networks that can come in useful in your working life.

Class plays a role too, as parents who have the time to volunteer to gain priority access tend to have more secure, well-paying jobs, or are homemakers married to spouses with those kinds of jobs.

To be sure, there is nothing very nefarious about privilege being passed on – it is the trait of societies that stratification is transmitted to future generations, as parents pass on their socio-economic advantages to their children. So the taxi driver’s son who managed to get into a brand-name school in the past and becomes a lawyer, thus joining the elite ranks, will pass on his advantages and alumni access to his son. That lawyer’s son may then gain a coveted place in a brand-name school, depriving today’s taxi driver’s son of one.

In that way, those without connections today will find it harder to break into circles of privilege than those in the past. This is a very simplistic example, but is illustrative of how societies can become stratified along socio-economic status over time.

The system of giving priority admission for alumni members and community volunteers has continued for decades, despite its clearly detrimental effect on social cohesion, creating a society where connections determine what school your child goes to. In my view, the negative social effects outweigh positive effects, such as maintaining school tradition.

.

RELATED STORY

Government concerned about lack of diversity in some schools, housing estates: Grace Fu

Minister for Culture, Community and Youth Grace Fu pointed out that Singaporeans are mixing through sport, arts, volunteerism and at the workplace. ST PHOTO: KUA CHEE SIONG

.

Thinking Aloud

Class divide and inequality make for poor mix

.

In 2013, PM Lee highlighted the problem of some popular primary schools becoming “closed institutions” open only to those with alumni or family connections to the school. The Government has since kept at least one class of 40 places open in all schools, for those without connections to the school.

Today, we have Workfare, the Progressive Wage Model and any number of schemes to boost the incomes of those with low-paying jobs. As PM Lee made clear, income inequality is now being dealt with seriously.

Still, I think other aspects of the inequality debate deserve a hearing. Our school admission policy is just one rather obvious example of how inequality is allowed to perpetuate. Are other social policies exacerbating inequality?

Unlike low-wage workers or poverty, inequality is harder to root out because it can’t be captured by one figure or income. Inequality is always about relativities: relative access to public goods, relative privilege, relative well-being.

And its effects are more insidious.

Inequality will eat away at our sense of society, if people start to doubt that the Singapore system is fair to all – especially those without wealth and without connections.

The last thing we want is for people to feel that the country is not just ruled by the elite, but for the elite.

I am coming to think that inequality is nothing less than a major societal-wide threat for Singapore.

Social security – such as having a sense of cohesion – is as vital to our national survival as food and water security. Inequality risks disrupting that cohesion and is, in that sense, an existential threat. Just as we have faced up to the issues of terrorism, cyber security and fake news, we need to face up to the threat that inequality poses to Singapore.

We should face it, name it, and unpack what contributes to inequality, so that we can make our system more equal.

‘To live in a class bubble – elite or otherwise – is to suffer a poverty of experience, she said, because the world is made up of people of many different backgrounds. She has friends at both extremes: those who are very class-conscious and those who are not. It was obvious to her that the latter led lives rich in meaning and friendship.’

‘To live in a class bubble – elite or otherwise – is to suffer a poverty of experience, she said, because the world is made up of people of many different backgrounds. She has friends at both extremes: those who are very class-conscious and those who are not. It was obvious to her that the latter led lives rich in meaning and friendship.’