OP-ED COLUMNISTS: OPINION ON PAGE ONE BY FRANCISCO TATAD – We’re out of rice, Boracay is shut down, what’s next?

OPINION ON PAGE ONE BY FRANCISCO TATAD

CONTRARY to the political propaganda, the incidence of poverty in the Philippines is growing—and it is a rural and agriculture-based phenomenon. This is what the statistics from the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and the Philippine Statistics Authority tell us. Urban poverty has not been banished, but the urban poor have a new technological view of their condition. The poor in Samar or in Caraga are poor because they don’t have enough to eat; the poor in Tondo or Payatas are poor because on top of everything else, they are not on Twitter or Facebook. It’s no longer merely a question of whether or not they eat.

Manila has run out of rice, the nation’s staple, according to this paper’s headline story on Wednesday. But this is presented simply as the National Food Authority’s failure to import enough rice on time rather than the result of a major policy disorder. In reality, it is the long-term effect of a wrongheaded agricultural policy that has made poverty incidence in our agricultural economy 20 times higher than that of Malaysia, three times higher than that of Vietnam, and twice higher than that of Indonesia and Thailand. The rationale is that we have to import rice year after year because our rice-eating population is growing, and our rice-growing farmers are not producing enough.

Too many eaters?

The “reproductive health” people have managed to blame normally reproducing families for the recurring rice shortage. They simply eat too much rice. No one has bothered to point out that our general economic performance has not allowed us to produce more of what we should, and less of what we shouldn’t. The government is fixated on building giant casinos and creating more playing grounds for the overflow of mainland Chinese, instead of trying to increase the nation’s capability to produce more food. Large tracts of agricultural lands in Luzon and elsewhere have reportedly been acquired by Filipino “dummies” for food production activities of their Chinese financiers, but not for Filipinos.

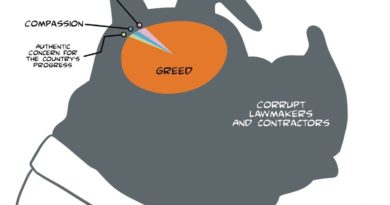

The way our propagandists hype our so-called growth rate and the growing number of dollar billionaires who make it to the yearly listing of the otherwise insignificant US-based Forbes magazine, you would think the Philippines is about to finally abolish poverty and join the ranks of the First World countries. Not by a long stretch. Based on reputable statistics, the poverty index is moving sharply and persistently in the opposite direction.

Poorer than Asean 4

For 2015, the Philippines has a poverty incidence of 21.6 percent, of which 30 percent is rural and an estimated 11 percent urban.

For 2014, Malaysia has a poverty incidence of 0.6 percent—less than 1 percent—of which 1.6 percent is rural, and 0.3 percent urban.

For 2015, Vietnam has a poverty incidence of 7percent, of which an estimated 8.7 percent is rural, and an estimated 3.8 percent is urban.

For 2013, Thailand has a poverty incidence of 10.5 percent, of which 13.9 percent is rural, and 7.7 percent is urban.

For 2016, Indonesia has a poverty incidence of 10.9 percent, of which 14.1 percent is rural, and 7.8 is urban.

Poverty incidence among Filipino farmers and fisherfolk is higher than the national average—34.3 percent for farmers, and 34percent for fisherfolk.

There appears to be a direct correlation between the poverty level of the farmers and fisherfolk and the agricultural policies of government. The particular focus on rice production, despite its less than satisfactory results, has effectively prevented the diversification into other crops and agricultural products, especially tree crops like coffee, cacao, rubber and oil palm.

The biggest single victim is coconut, which has suffered criminal neglect from government. For a number of years, a huge international lobby tried to spread the rumor that the use of coconut oil and other products was allegedly harmful to one’s health. That lobby ultimately failed, and coconut regained its standing in the market and the pharmaceutical world. But because of lack of government support for the industry, some coconut planters started cutting down old coconut tree for lumber without replacing them with new trees.

Coconut sacrificed

There are 3.5 million hectares of land planted to coconut, as against 3.2 million hectares planted to rice. But for decades, over half of the budget for agriculture has gone to rice, with but a pittance going to coconut. In addition, the government started collecting a coconut levy fund from the first domestic sale of the product from 1972 to 1982, raising P9.69 billion, which has since ballooned into P74 billion in cash and an estimated P150 billion in assets. The levy made the coconut farmers the most heavily taxed class of citizens in the country, without their being aware of it. They finally learned of it when the levy began to impact directly on their daily lives.

The Supreme Court has ruled that the coconut farmers are the beneficial owners of the coco levy fund, but to date, no institutional mechanism exists to ensure that they actually benefit from it. The coconut farmers are determined to fight for it, but without Malacañang’s active support, it promises to be a long fight. This is one priority issue that should truly concern the DU30 government.

Going back to rice, public attention at this time is focused solely on the feuding National Food Authority Council officials. who are trying to blame each other for the disappearance of the staple in Metro Manila. Who is ultimately to blame, and who will President Rodrigo Duterte sack if he is indeed in a sacking mood—between his all-powerful Cabinet Secretary and NFA Council Chair Leoncio Evasco Jr. and the “maverick” NFA administrator Col. Jason Aquino? Now that cheap rice has disappeared from the market, who among the rice-importing officials would have the nerve and acid tongue to tell the rice-hungry rabble like Marie Antoinette to eat cake instead?

Rethinking policy

The rice importation issue will have to be squarely faced. But after and beyond it, DU30 and the Cabinet, not to mention the few remaining functioning heads in Congress, must seriously reexamine the agriculture policy of government. What is the real policy coming from the Cabinet and Congress, and left in the hands of the Department of Agriculture to implement? Is there one at all, or has Agriculture Secretary Manny Piñol been allowed to simply concoct his own brainstorm and pass it on as the policy of the Cabinet and Congress?

This question is pivotal, because there are any number of Cabinet members who seem to believe they have the right to dictate what policies the Cabinet must adopt with respect to their respective departments, instead of simply leading all policy discussions related to their departments and acting as the primary agency to implement all approved Cabinet policies.

With respect to the DA, this means the Cabinet and Congress must decide first of all whether we are going to provide, year after year, the biggest budgetary support for the growing of rice at the expense of any and all other crops, only to raise more money later to import the grain from our rice-growing and exporting neighbors, because our crop has failed or our harvest was not enough.

In terms of costs and yields, it seems utterly foolish for our farmers to believe they could compete favorably with their Southeast Asian counterparts along the Mekong River, the longest river in Southeast Asia which flows through China, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, with a basin area of 795,000 square kilometers, who do not have to worry about irrigation and are fully supported by their respective governments.

More high-value crops

Our farm productivity has lagged so far behind that of all our rice-growing neighbors that the more sensible agriculturists, economists and even plain columnists have not ceased to wonder why our farmers insist on planting rice when they could be planting other high-yielding crops instead. Even the lowly moringa, which grew in abundance around my late grandmother’s house and was the most reliable item in her vegetable diet when I was a young kid, and the equally lowly ginger, turmeric and lemongrass have become highly popular not only among young foodists.

Our agriculture needs some serious, long-term planning. I realize planning is not one of DU30’s strongest suits—he has just decided to close down Boracay island to national and international tourism effective the 26th of this month, without any consultation with the affected establishments on any transition arrangements. Effective that date, all flights to and from Boracay will cease. For the country as a whole, not just for Boracay, this will be the end of world-class tourism as we know it.

With rice for the people gone, and the only notable tourism grinding to a halt, the DU30 administration has just bought for itself a first-class crisis. It will tend to grow bigger if and when the government fails to see it for what it is.