POLITICS-OPINION: JAKARTA – 20 Years Since Beginning of Reformasi, How Far Have We Come?

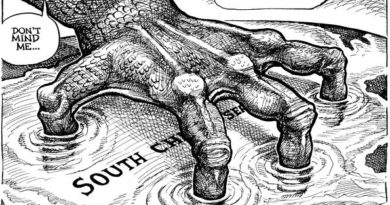

Jakarta. This year, the month of May comes with a bittersweet blend of history and progress, as Indonesia observes the 20th anniversary since the downfall of Suharto’s regime and the beginning of reforms known as reformasi.

The regime change was triggered by months of financial crisis that rattled Asian countries, leading to mass protests, which resulted in political turmoil and power games marred by social unrest, riots and forced disappearances of activists.

During Suharto’s 32-year rule, the Indonesian economy experienced rapid growth, steep poverty reduction and broad expansion of higher education and health care. However, the same period was also rife with restrictions on freedom of press and expression, human rights abuses, rigged elections and rampant corruption.

When the New Order regime fell and an opportunity for major reform became possible, the nation called for a number of changes, including: amendments to the 1945 Constitution; freedom of expression, abolition of the so-called dwifungsi (a military doctrine placing the Army as both a socio-political and defense force); introduction of the rule of law, human rights; and eradication of corruption, collusion, nepotism.

How far have we come since 1998?

Freedom and Democracy

“During the New Order regime, freedom was costly. People couldn’t freely express themselves or criticize the government, and the press was restricted,” said Ansy Lema, a former 1998 activist and lecturer at the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences of Universitas Nasional (Unas) in Jakarta.

Savic Ali, director of online affairs of Indonesia’s largest Islamic organization Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), also a former organizer of the 1998 student demonstrations, echoed the words of Ansy.

“This is a blessing, because today we enjoy freedom, freedom of expression, freedom of the press, freedom to associate, freedom to establish organizations, to create communities. We are enjoying freedoms that we did not have before. And we no longer live in fear,” he told the Jakarta Globe.

When Suharto was in power, the press was severely repressed, with overly critical journalists disappearing or thrown in jail. Debates on domestic politics were also restricted, showing a stark contrast in comparison to the lively discussions Indonesians have nowadays.

“We couldn’t criticize the government, we could be jailed or made disappear,” Ansy added.

The process toward a more democratic Indonesia began immediately after Suharto stepped down on May 21, with countless amendments to legislation in the following years, which involved including a new chapter on human rights and the lifting of restrictions on freedom of expression and association.

The political reforms of the late 1990s and early 2000s also resulted in more open and transparent governance, with decentralization aiming at equal distribution of power.

“Reformasi allowed us to have a more genuine democracy, not merely a pseudo-democracy … Public participation during the New Order was distorted, because the people were forced to do it,” said Djayadi Hanan, domestic politics lecturer from Paramadina University.

In contrast, the years after reformasi showed political competition and accountability, most notably through general elections, which have been held regularly and openly, Djayadi added.

Now we have multiple political parties, under the New Order there were only three. The military and police, which earlier were one, also no longer have seats at the House of Representatives.

Human Rights

Reformasi also came with calls on the government to address past human rights abuses, including the 1965 anti-communist purges and murders and disappearances of activists.

Although the National Commission on Human Rights (Komnas HAM) has been examining the abuses that took place since 1965, activists argue the government has yet to show a real commitment to resolve them.

“There is a lack of will from the government to resolve past cases of human rights abuses, even though it’s included in President Jokowi’s [Joko Widodo] Nawa Cita [agenda],” said Nursyahbani Katjasungkana, human rights activist and coordinator of the International People’s Tribunal on 1965 Crimes Against Humanity (IPT 1965).

Indriyanti Suparno, a commissioner at the National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komnas Perempuan), told the Jakarta Globe that the past 20 years have been marred by flawed law enforcement and impunity for perpetrators of abuses.

“For example, those who were probably involved in the events [riots] of 1998 are still holding strategic offices in the country. This affects the space that the victims can access, whether for recovery, justice or to obtain their rights,” Indriyanti said.

Both Nursyahbani and Indriyanti also highlighted various progressive policies adopted in the past 20 years, including ratification of international conventions concerning human rights, efforts to end violence against women, and prioritizing women’s issues in national programs.

However, their implementation is not yet satisfactory.

“There is still a huge problem in terms of implementation, because our political culture has not really transformed. Corruption is still rampant, law enforcement is weak and neglectful of minority groups,” Nursyahbani said.

According to Indriyanti, a lack of political will affects the implementation process.

“Though we have policies protecting women, they are difficult to realize when the political will of lawmakers is not there,” she said.

Savic also touched on this aspect by saying that many active politicians “are still acting like New Order politicians.”

Shortcomings

While it can be said that Indonesia has come a long way since the change of regime, it still faces a number of challenges, some of which are threats to the democratic future.

Djayadi stressed that Indonesian democracy must be strengthened, particularly through law enforcement and the government’s responsiveness to the needs of the people and inequality.

“Without proper law enforcement, our democracy will be eroded. When the law is not upheld, the progress will lessen,” he said.

According to data from the Central Statistics Agency (BPS), Indonesia’s Gini ratio was higher in 2017, at 0.391, compared with 2002, when it stood at 0.341. The Gini coefficient is used to measure income inequality, with lower values reflecting lower inequality.

“In terms of political disparity, only certain groups can amass power through specific mechanisms. Only those with money can rule, while others cannot, and this is still happening,” said Djayadi, who is also executive director at Saiful Mujani Research and Consulting (SMRC).

The government, with complex bureaucratic procedures, still lacks adequate responsiveness to the needs of the people.

“Bureaucratic reforms must be implemented to serve the people, not complicate things for them,” Djayadi said.

Freedom Without Order

Is there such a thing as too much freedom? Rising intolerance, along with the spread of fake news and hate speech seem to suggest the increasing need for more order.

According to Ansy, democracy is not merely a matter of freedom, but also that of order. The two must go hand in hand for a country to truly reap the benefits of democracy.

“During the New Order regime, freedom was expensive. Whereas now, in the age of reformasi, what’s expensive is order,” he said.

Similarly, according to Nursyahbani, the developments concerning freedom, including that of the press and expression, have not resulted in a positive contribution toward democratization.

“Instead, they are creating division in society. We see so many cases of hate speech, because there is a gap between developments in technology and democracy,” she said, adding that education will be key to address this issue.

As reformasi continues to provide room for citizens to participate in politics, Savic says many people are becoming confused by the massive amount of information available, and falsely assume that life was better during the times of Suharto.

“They were not used to facing various opinions, and suddenly there are all these different views. They become confused and think ‘life is worse than before,’ while in reality, that isn’t true.”

Despite the notable challenges, there seem to be shared optimism on the future of Indonesia. The strength of civil society in the country illustrates the potency of social justice movements to bring real change.

“Another achievement in these 20 years of reforms is the consolidation of civil society. We continue to garner tools and alternatives to ensure rights for all. In the past, we didn’t have many opportunities, but now they are expanding,” Indriyanti said.

She added that advocacy and hard work will continue.

Savic, who also founded Islami.co, a website promoting moderate Islamic teachings, said he believes Indonesia will continue to be religiously moderate and progressive.

“I see passion and spirit in the younger generation. I still believe in freedom, in our politics and our economy,” he said.

Additional reporting by Andre Woolgar.