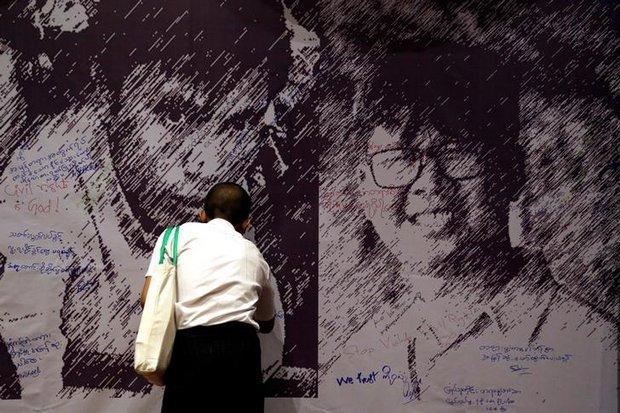

POLITICS: YANGON – How two young reporters shook Myanmar

A man signs a large poster in Yangon showing the jailed journalists Wa Lone (right) and Kyaw Soe Oo. (Reuters photos)

.

YANGON: Late in the afternoon of Dec 12 last year, Wa Lone’s cell phone rang. It was a man named Naing Lin, a lance corporal in Myanmar’s 8th Security Police Battalion.

The policeman urged Wa Lone, a 31-year-old reporter with Reuters, to meet him immediately at the battalion’s barracks on the outskirts of Yangon. Night was falling around the golden spires of the pagodas in this former capital city.

“He told me that if I don’t come now,” Wa Lone would later recall in a Myanmar courtroom, “I might not be able to meet him because he is about to transfer to another region.”

Wa Lone, whose large eyeglasses rest on chubby cheeks, had spent weeks looking into Battalion 8. He was working on a story about the murder of 10 members of the country’s Rohingya Muslim minority during a military operation in western Rakhine State. And he’d gotten his hands on explosive material: photographs of the 10 men before and after they were killed.

One picture showed the men’s bodies, hacked and shot to death, in a shallow grave. Another, taken while they were still alive, showed them on their knees. In the background, milling around with assault rifles, were members of Battalion 8.

Before going to meet the lance corporal, Wa Lone checked in with the Reuters bureau chief, Antoni Slodkowski, who told him to take another reporter along. That man, 27-year-old Kyaw Soe Oo, was visiting from Rakhine State and had recently been hired by the news agency.

Setting out at about 6pm, the bureau’s white Nissan SUV crossed an overpass that overlooks Inya Lake, ringed by homes of Myanmar’s elite, including the nation’s de facto leader, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi. It was a world beyond the reach of Wa Lone, the son of a rice farmer from a village of a few hundred people.

About halfway to the Battalion 8 compound, the SUV was stuck in traffic. Wa Lone later remembered feeling uneasy: Why had the policeman insisted on him coming right away? The reporters discussed turning around. But they decided to push on.

Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo made it to the entrance of Battalion 8 around 8pm. After meeting Lance Corporal Naing Lin and a second policeman, the reporters said in court, they went with the cops down the street to an open-air beer garden. The men ordered beer and fish crackers. They talked about Rakhine State, Naing Lin recalled in court testimony. He told the reporters about coming under attack by Rohingya insurgents on Aug 25 last year, as the militants launched a series of assaults on police stations.

When it was time to go, Wa Lone later said in court, Naing Lin handed him a copy of the Myanmar Alin, a state-run newspaper, rolled up with some documents inside. As the two reporters left the restaurant, they were surrounded by men in civilian clothes. “These are secret documents!” Wa Lone recalled one man shouting. A pair of handcuffs was slapped on Wa Lone’s wrists, and another on Kyaw Soe Oo’s. They were then pulled into two parked cars.

Naing Lin recalls the encounter differently. He testified in court that Wa Lone called him on Dec 12 to request a meeting, and that when he met the two reporters at the beer garden, he came alone. He also denied giving Wa Lone any documents.

With their arrest, the two reporters were thrust into the murky confluence of military and civilian rule in this ethnically fractured nation of some 50 million people. To dignitaries in Western capitals, from Pope Francis to former US President Bill Clinton, their incarceration would become a test of press freedom in Myanmar, and how far the country has travelled toward a more open society. On July 9, a judge charged the two under the Official Secrets Act, a law that carries a maximum sentence of 14 years.

At the beginning of this decade, Myanmar was a focus of hopes for democratic progress in Southeast Asia, a neighbourhood long marked by strongman regimes. Aung San Suu Kyi was released in 2010 after about 15 years of house arrest under a military government. In 2015, her party swept general elections.

Aung San Suu Kyi, shown in 2010 with supporters, was once jailed in the same prison where the two Reuters reporters are now held.

Aung San Suu Kyi, shown in 2010 with supporters, was once jailed in the same prison where the two Reuters reporters are now held.

.

For the youth of Myanmar, like Wa Lone, that sharp turn of events brought a sudden, historically improbable expectation of freedom after decades of brutal military rule. But the army never fully relinquished power: In 2008, it put in place a constitution granting itself broad powers and control of key ministries.

And peace has not come to Myanmar. Deadly ethnic conflicts, obscure to most of the world but bloody at home, have continued to rumble.

Last year, widespread enmity for the country’s best-known ethnic minority, the Rohingya Muslims, fed a savage military campaign that forced some 700,000 people to flee their homes for Bangladesh. Now, the Myanmar army stands accused by United Nations officials of having committed widespread killings, mass rape and ethnic cleansing. In the face of this condemnation, Suu Kyi has not uttered a word of public criticism of the armed forces.

A spokesman for Aung San Suu Kyi, Zaw Htay, and an Army spokesman did not respond to requests for comment for this article. Zaw Htay has said that Myanmar’s courts are independent and the reporters are receiving a fair trial. The military has denied its troops took part in ethnic cleansing in Rakhine State last year.

Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo’s reporting on the massacre of the 10 Rohingya men was published by Reuters in February. The article placed them at odds with their country’s Buddhist majority, to which the reporters, Aung San Suu Kyi and top military leaders all belong. Much of that majority despises the Rohingya, viewing them as foreign interlopers from South Asia. It was groundbreaking investigative journalism in Myanmar. But to their own people, the reporters’ quest for truth was an act of betrayal.

The pair have been behind bars for almost eight months, most of that time at Yangon’s Insein Prison, a hulking edifice of 19th century British colonial architecture that has held thousands of political prisoners, including Aung San Suu Kyi herself for a brief period. And they have been appearing in court since January, sitting through more than 30 hearings. A verdict in their trial could be handed down in the coming weeks.

The story of the two reporters and their roles in Myanmar’s experiment with press freedom is pieced together from their testimony and that of police at their trial. It also draws on other accounts given by Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo and interviews with their colleagues, their relatives and their friends.

The day after their arrest, an order was issued from the office of the nation’s then-president authorising police to pursue charges against the two reporters. Then, for two weeks, Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo disappeared without a trace into the hands of the police.

THE MAKING OF A NON-CONFORMIST

Wa Lone’s collision with the state was, in many ways, a long time coming.

He grew up in a traditional wood clapboard house, built by his grandfather in the small village of Kin Pyit, with a population of less than 500. Reached by a skinny dirt road, the village is an island among outstretched rice paddies.

When Wa Lone was a boy, his father, a rice farmer named Tin Myint, needed to borrow money before planting. At harvest season, he was forced to sell a quota of his rice below market price to the local military administration. “It was not enough, we had to take out loans to plant the next crop,” said Wa Lone’s younger brother, Thura Aung.

Money was tight. Meals were usually rice with vegetables, rarely with the added expense of meat, said Thura Aung.

Wa Lone was unwilling to accept such frustrations, Tin Myint said. “He was really impatient. He always said, ‘Where is the improvement? How are we going to improve our lives if we keep going like this?'” he said.

Wa Lone travelled to Yangon in 2004, the country’s former capital and still its main city, and got a job in a welding shop. The pay was bad and he didn’t know much about welding. “They treated us like – I wouldn’t say slaves, but something like that,” is how Wa Lone describes the experience.

A few months later, he moved to Mawlamyine, a smaller city about a six-hour drive from Yangon. It sits near the shores of the Andaman Sea, and he had an uncle who lived at a neighbourhood monastery there.

His mother died of breast cancer at the end of 2005, but Wa Lone didn’t receive word until two months after her death, when a monk from his village visited the monastery and passed on the news. The first job he got in Mawlamyine was unloading vegetables at a night market. He was still a teenager.

While living in the city, Wa Lone and four friends began hanging out after work at a large monastery down the street from his uncle. It had a reading room, a project funded by the British Embassy and British Council to stock libraries with English books in cities across Myanmar. The group took an English language class for a while, but mostly they read books and talked.

In 2007, Wa Lone and his friends followed news reports as protests gripped the nation. Known as the Saffron Revolution, the uprising included long processions of Buddhist monks taking to the streets in defiance of the military junta. The junta cracked down, reportedly killing at least 31 people and arresting thousands.

In 2009, Wa Lone heard about other young people from Myanmar meeting in Thailand to discuss democracy. He spent more than two months there with them, talking about political theory and reading books such as George Orwell’s Animal Farm. Wa Lone watched documentaries about protest movements – the Orange Revolution in Ukraine, the American Civil Rights movement, the struggle against apartheid in South Africa.

Wa Lone said he returned to Mawlamyine inspired to do more for the people of his country. He didn’t want to get arrested or confront the authorities – both, he reasoned, would be bad for his family. He continued with volunteer work and charity drives to fund monastery schools.

Around him, the nation’s politics were changing. Aung San Suu Kyi was released in 2010. The military junta installed a quasi-civilian regime led by ex-generals the next year. The decision by Suu Kyi’s party, the National League for Democracy, to contest by-elections in 2012 was thrilling, said Kyaw Naing Oo, one of the circle of friends in Mawlamyine. Now in his mid-thirties, he runs a charity school.

“At the time of the election we really hoped for more freedom because it was a democratic party,” said Kyaw Naing Oo, “and Aung San Suu Kyi is a democratic icon.”

In a monastery where Wa Lone stayed in Mawlamyine, a small house at the end of an alley, another member of his family recently received visitors. Aww Bar Sa, who is a monk and Wa Lone’s second cousin, gestured for the reporters to follow him upstairs. A golden Buddha sat in a shrine, with flashing red, blue and green LED lights all around.

As boys of the same age, Wa Lone and Aww Bar Sa grew up together in Kin Pyit village. “Since he was young he would argue about whether the world is round or flat, or whether the world is moving or standing still,” Aww Bar Sa said, laughing at the memories of Wa Lone. “He would argue about such things. Many in the village did not understand these topics.”

Asked about Wa Lone’s journalism, Aww Bar Sa grew more solemn.

“The country’s development is still slow. People don’t have much knowledge yet. There are still many superstitions,” said Aww Bar Sa. “So, if you don’t write from the side of your own religion, they think of you as a traitor.”

That sentiment is evident in the comments posted on a Facebook page set up by Reuters – “Free Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo” – after the arrests. The page has photographs of Kyaw Soe Oo, in handcuffs, hugging his two-year-old daughter. There’s Wa Lone beside his pregnant wife, and his wife without him, crying. Below, visitors posted a string of slurs and threats.

“They are traitors”

“They are disgusting”

“They should be given the death sentence”

The Rohingya aren’t afforded citizenship. Their very ethnicity is not recognised by Myanmar officialdom. Many of the Rohingya still in the country live in isolated colonies that are a cross between shanty towns and internment camps. They are, according to Human Rights Watch, “one of the largest stateless populations in the world.”

“I don’t use the word ‘Rohingya’,” says Aye Chan, a nationalist activist from Rakhine State who is now promoting the settlement of Buddhists in the areas where the Rohingya lived before they fled. “They are Bengalis. They’re from Bangladesh.”

Aye Chan socialised with Aung San Suu Kyi when both were studying in Japan in the 1980s, and he himself was jailed for seven years for supporting democratic reform during the junta era. Seated in the lobby of Yangon’s Lotte Hotel, with a view of Inya Lake outside, he spelled out his take on the current crisis.

He visited abandoned Muslim villages days after the Rohingya fled, which he said put him in a position to dispel allegations of mass rape and other atrocities by Myanmar soldiers. As evidence, he cited meeting with an officer in the area. “I asked one of the border police, an officer, ‘There are accusations about you of raping these women?’ He laughed. And he said: ‘These women don’t bathe even once in a week. How can we sleep with them?'”

In Aung San Suu Kyi’s speeches, she avoids the term “Rohingya” in favour of “Muslims,” a word that denotes religion but not homeland.

Sitting down at a hotel restaurant in the capital city of Nay Pyi Taw, an aide to Aung San Suu Kyi spoke in support of her.

The situation inside Myanmar, behind closed doors, is more nuanced than it might appear to outsiders who urge Aung San Suu Kyi to speak out on behalf of the Rohingya, said Sean Turnell, an Australian academic who serves as her special economic consultant.

“‘Nobel Prize winner overseeing genocide’ is a damn good headline, I get it,” he said.

But under the 2008 constitution, the military is “completely beyond the control of the civilian government,” said Turnell. The civilian government “has no de jure supervision and no de facto supervision. At all. Zero.”

More than that, Myanmar’s constitution provides that if a state of emergency is declared, the commander-in-chief can be granted total control of the country under circumstances including “disintegration of national solidarity.”

TESTING THE LIMITS OF PRESS FREEDOM

Slodkowski, the Reuters bureau chief, first met Wa Lone in 2016.

Wa Lone didn’t speak English as well as another candidate Slodkowski was interviewing: “I had trouble understanding everything he said.” But Wa Lone struck him as both curious and driven.

That was important to Slodkowski, who had been coming to Myanmar since 2009. Slodkowski’s father was an underground journalist in Poland who was arrested in 1982 and spent a year and a half in prison under an authoritarian communist regime.

Wa Lone soon landed a job at Reuters. He’d been in Yangon for about six years at that point, doing charity work, taking English classes and working his way through a series of local newspapers.

He met the woman who became his wife, Pan Ei Mon, at one of them, the Myanmar Times. The first time they went for coffee, in 2013, Wa Lone asked Pan Ei Mon whether she had a boyfriend. She said that she did. “He said, ‘Okay, why don’t you choose between him and me,'” she recalled, smiling at the memory.

Before joining Reuters, he’d built a reputation for reporting about the country’s internal armed conflicts. At the Myanmar Times, where he worked for about three years, Wa Lone was one of the first reporters to reach an embattled border region in Shan State after a bout of fighting in 2015 between the military and an armed ethnic militia.

Such violence has a long history in Myanmar. Civil warfare began almost immediately after independence in 1948. Ethnic divisions that erupted in fighting back then have endured. More than 20 armed groups pose a central challenge for Aung San Suu Kyi and her government, who are pursuing national peace talks. To the north of Shan State, for example, among jade, amber and gold mines, it is the Kachin Independence Army trading fire with government troops.

After arriving at Reuters, Wa Lone soon began reporting about Rakhine State and the Rohingya Muslims. A story in October 2016 detailed allegations that Myanmar soldiers raped eight Rohingya women at gunpoint after coordinated Rohingya insurgent attacks on border posts. With Wa Lone’s name atop, the story quoted a Rohingya woman saying of a group of soldiers: “Two men held me, one holding each arm, and another one held me by my hair from the back and they raped me.” Government spokesman Zaw Htay denied the allegations when the story was published.

Wa Lone covered attacks by Rohingya Muslim militants as well. In August of 2017, he reported on official accounts of coordinated assaults by the militants on 30 police posts and an army base, killing 12 members of the country’s security forces. Those attacks would spark the military’s crackdown in Rakhine State.

The reporting traced a pattern in Rakhine in which insurgent strikes on security forces were met with overwhelming force that drove increasing numbers of Rohingya Muslims to flee the area.

Wa Lone pursued his job while facing difficulties making ends meet. His wife, Pan Ei Mon, said Wa Lone made the equivalent of $1,000 a month at Reuters, and she earned about $380 working in the advertising department of a local newspaper. Wa Lone’s annual income alone was about 10 times the country’s per capita gross national income. But living in the centre of Yangon, Pan Ei Mon said, “It was never enough.”

They lived in a small apartment, a space subdivided from their landlady’s house. With Reuters headquarters often slow to reimburse their expenses in the far-off Yangon bureau, reporters there said they sometimes ran out of money after long trips before the next check. Both Pan Ei Mon and Wa Lone pawned their wedding rings. They used an older friend at the Myanmar Times to take the jewellery to avoid embarrassment, said Pan Ei Mon. On one occasion, Wa Lone used the cash to help pay for a reporting trip to Rakhine State.

Asked about its slowness to pay expenses in Yangon, Reuters said its global system for reimbursing reporters depends on using a credit card that isn’t widely accepted in Myanmar. In recent months, the news agency said in a written statement, it has made it possible for staff there to be reimbursed more frequently. On the pawning of the wedding rings, Reuters said: “We were not aware of this personal sacrifice and it is not something we would ever ask or expect of staff.”

In investigating the massacre, Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo were on dangerous ground, said Myat Swe, co-founder of the Myanmar Times. He was arrested in 2004 by the military junta after his father, an intelligence officer, was purged. He spent about nine years behind bars for allegedly violating censorship laws. “What they did was they threw me in the prison first and then they looked for the case,” said Myat Swe, now chief executive at Frontier Myanmar magazine.

The military, he said, retains vast power, which Aung San Suu Kyi is unable to check. “You can clearly see that she doesn’t have any influence whatsoever on the military,” said Myat Swe, sitting in a second-floor office where production notes for his magazine were scribbled on glass walls.

That made Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo’s reporting “quite risky,” he said, especially in Rakhine State, where the government is aware of reporters’ movements and locals don’t like journalists, domestic or foreign.

Under the junta, which lasted half a century, Myanmar had what was regarded as one of the world’s strictest systems of censorship. After the junta installed a quasi-civilian government, the country announced in 2012 that it was ending pre-publication censorship of news reports. Later that year, it said that private daily newspapers, shut down since 1964, could be published.

A fitful loosening and tightening followed – 10 journalists and media executives were imprisoned in 2014, for example. As Aung San Suu Kyi’s party took power in 2016, expectations rose that she would introduce an era of greater press freedom.

But journalists continue to be incarcerated. In June last year, the military arrested three Myanmar reporters in Shan State for covering a drug-burning event by an ethnic militia. They were charged under the Unlawful Associations Act, a colonial-era law that broadly prohibits contact with banned groups. The charges were dropped in September.

Former Reuters journalist Aung Hla Tun knows what it is like to cover the military. Ushering visitors into his office in Nay Pyi Taw, he pointed to an internal Reuters reporting award on a shelf which he won for covering the Saffron Revolution protests in 2007. “I got a chance to do my bit for democracy, for freedom of press for Myanmar,” he said.

That year, he produced a series of reports from the streets as protesters defied the junta. In an internal Reuters note circulated in October of 2007, Aung Hla Tun was praised for displaying “enormous courage, resourcefulness and journalistic integrity in putting us consistently ahead on the major breaks and turns in the story.”

He is no longer a reporter. Aung Hla Tun left Reuters at the end of 2016 and was named Myanmar’s deputy information minister in January 2018. He said he chose to serve in the government out of loyalty to Aung San Suu Kyi.

Sitting on a sofa, dressed like a typical Myanmar official in a traditional sarong-like garment called a longyi, with neatly combed hair, glasses and placid expression, he recounted the stories of his own family members arrested by the former military regime.

He also talked about Wa Lone.

Aung Hla Tun worked with Wa Lone briefly in the Reuters bureau and knew him before that as a member of the reporting community in Yangon. While at the Myanmar Times, Wa Lone said he attended sessions that Aung Hla Tun hosted for journalists looking to brush up their English and improve their time management.

They considered each other friends. Aung Hla Tun attended Wa Lone’s wedding in 2016. A snapshot from the day shows him on stage, a place of honour, with the beaming couple.

But Wa Lone said he and Aung Hla Tun disagreed over coverage of events in Rakhine State. At one point, Aung Hla Tun said, he gave Wa Lone advice: “be careful”.

The 10 Rohingya Muslim men pictured here were massacred soon after this photograph was taken last September. The photo, obtained from a local Buddhist elder, was a crucial piece of evidence for Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo as they reported the role of Myanmar security forces in the massacre.

The 10 Rohingya Muslim men pictured here were massacred soon after this photograph was taken last September. The photo, obtained from a local Buddhist elder, was a crucial piece of evidence for Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo as they reported the role of Myanmar security forces in the massacre.

.

The prior Reuters bureau chief in Yangon, Paul Mooney, said Aung Hla Tun referred to Rohingya Muslims as “Bengalis”, a term implying they are foreigners that’s commonly used in Myanmar. When Buddhists attacked Muslims during riots in the city of Mandalay in 2014, Mooney said, Aung Hla Tun only wanted to relay official comment from the capital. “If there was anything negative that might kind of make the Burmese army look bad, he didn’t want to be involved with it,” Mooney said.

Aung Hla Tun disputed Mooney’s descriptions of him. Mooney, he said, tried to paint him as “anti-Muslim”. However, he said, “I have many Muslim friends.”

Aung Hla Tun said he had asked officials in the government about Wa Lone’s case. But, Aung Hla Tun said, he discovered that it was inadvisable to lobby for Wa Lone’s release: “Some close friends warned me, ‘You should stop or you will be in danger.'” He did not explain further.

“I have done my best, he was my friend,” he said.

His voice strained as he spoke about the news agency’s coverage of Rakhine State. “Reuters should have apologised to the government. Apologise!”

A MASS GRAVE IS DISCOVERED

In late October, Wa Lone flew to Sittwe, the capital of Rakhine. He was with a colleague, reporter Simon Lewis; the two met up with Kyaw Soe Oo after landing.

Where Wa Lone’s face is full and his eyes animated above a mustache, Kyaw Soe Oo has high cheekbones, his shoulders square on a leaner frame. As a kid in Sittwe, he helped out local shops arranging and dusting books, and in return was allowed to read them. As an adult, he stacked bookshelves from floor to ceiling in his home. He read the translated works of names like Kafka, Camus, Sartre.

His family owned boats and buses used to transport goods. When Kyaw Soe Oo told them he was going to marry a woman who worked as a household employee for his grandmother, they disapproved. He married her anyway.

His wife, Chit Su Win, complained about all the books he was buying, and Kyaw Soe Oo agreed not to add any more. “But then I bought more and lied to her, saying that I got those from my friends,” he said.

In 2012, riots exploded between Muslims and Buddhists in Rakhine State. Growing up in Sittwe, the state capital, Kyaw Soe Oo was a Buddhist living among Muslims his whole life. A family helper who prepared his school lunches was Muslim. In the aftermath of the 2012 unrest, he’d watched in dismay as Rakhine Buddhists “bullied” Muslims.

Kyaw Soe Oo said he felt compelled to report about the issue. “To be frank, I would rather be a property agent than a reporter,” he said. “But if we don’t solve this problem during my time, my daughter will suffer the consequences.”

After his arrest, his wife, Chit Su Win, moved to Yangon from Rakhine State. She says she’s now concerned it is unsafe to return. Many in the Buddhist majority back home in Sittwe were furious that Kyaw Soe Oo had helped a reporting effort about crimes against Muslims. He and Wa Lone have received a torrent of death threats on social media since their arrest.

“Because of the story, people in Rakhine really do not like my husband now,” she said of the massacre article.

While Lewis conducted interviews in Sittwe last October, Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo took a ferry and got motorbike taxis to head further into the state’s interior. On the way, Kyaw Soe Oo’s driver mentioned that 10 Muslim men had been killed in the area. He and Wa Lone switched rides so that Wa Lone could hear the details. As they cut past rice paddies, the wind whipping in their faces, the driver leaned back and shouted answers. There’d been 10 men killed by soldiers and a group of villagers with swords, he said.

The news was related in a matter-of-fact way. “He doesn’t like Muslims,” Wa Lone later explained. “I don’t think he thought this is a big crime – an issue of morality or something.”

They arrived at the village, called Inn Din, and others there repeated the story.

Lewis remembers Wa Lone calling him and saying: “These guys are telling us there is a grave and they are offering to show us. I’m not sure if we should do that.” Lewis added: “He was scared.”

The grave was hard to find. The reporters walked through bushes and noticed newly cut branches marking a path on the side of a hill. There were barely buried bones on the ground, said Wa Lone. There were other bones scattered nearby. Wa Lone thought to himself that a dog may have been gnawing on them.

During his trip, a villager gave Wa Lone a photograph of 10 Rohingya men kneeling with more than a dozen men behind them, many holding assault rifles. The 10 had been detained by security forces.

After returning to Yangon, Wa Lone obtained another picture. This one showed the bodies of the 10 Rohingya men in a shallow grave. It was the same men, in the same t-shirts, but now some were face down in the dirt, limbs splayed, others with mouths agape toward the heavens, and blood everywhere.

In the photograph of the men kneeling, there’s a man at the back left corner of the frame with a ball cap on backwards and holding a gun with what looked like the number eight written in Burmese on the stock. It was a clue: At least some of the men in the image belonged to Myanmar’s police battalion 8 – the same battalion as that of Lance Corporal Naing Lin, the man Wa Lone would later meet on the evening of Dec 12.

Wa Lone, said Slodkowski, grew “obsessed” with identifying the policemen in the photograph. At the time, the United Nations was alleging widespread abuses by the military in Rakhine State; the government responded by saying it would look into any evidence presented to it.

“Let’s give them evidence then,” Slodkowski recalls Wa Lone saying.

Wa Lone devised ways to meet Battalion 8 police members so he could ask for phone numbers of other officers. He plugged those numbers into the search bar of Facebook, which is wildly popular in Myanmar, said Slodkowski. He looked for faces that matched those in the background of the photograph of the 10 Rohingya men.

Wa Lone also printed an enlargement of at least one face from among the armed men standing behind the kneeling Rohingya, said Slodkowski. Wa Lone took the image to other officers of Battalion 8 and asked whether they recognised their comrade.

His pursuit of the members of Battalion 8 would ultimately land him in jail, according to testimony in his trial.

A Battalion 8 captain named Moe Yan Naing testified that the police planned to “entrap” Wa Lone. He said he was present when a police brigadier general told Naing Lin to call Wa Lone, arrange the meeting and plant documents on the reporter before arresting him.

The brigadier general, he testified, issued a blunt threat to the cops: “If you don’t get Wa Lone, you will go to jail.”

After saying so in court, Moe Yan Naing was sentenced to a year in prison for violating police discipline, a development that police said was unrelated to his testimony.

The prosecution also presented police witnesses who backed the official version of events: They said the two reporters were detained, already in possession of the documents, during a random search at a police checkpoint.

‘SHUT YOUR MOUTH’

On the night of their arrests, Kyaw Soe Oo said, he didn’t realise the men in plainclothes who surrounded Wa Lone were police. He was going to help Wa Lone but then was grabbed from behind. “I thought they were pickpockets,” Kyaw Soe Oo later testified.

At the police station, Wa Lone testified, the two reporters were confronted by more than a dozen men in uniform and plainclothes. One asked Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo if they were spies. When Wa Lone said he didn’t know what was in the documents Naing Lin had handed him, a cop replied: “Shut your mouth.”

Next, both reporters later testified, they were taken to a building not far from downtown Yangon. It was the Aung Tha Pyay interrogation centre, a nondescript building where special branch police officers do their work.

Wa Lone said the police pulled a fabric sack over his head on the way there. He was then picked up by his armpits and carried up a set of stairs. When the sack was pulled off, there were officers sitting behind a table in front of him.

The interrogators, Wa Lone told the court, already had a list of the policemen he’d spoken to. They demanded he answer the same questions, over and over, in two-hour sessions, for almost three days straight: What did the policemen of Battalion 8 tell him? What was he reporting on?

In those sleepless days of interrogation, Wa Lone told the court, the police pressured him to share his cell phone password. He resisted. The phone, he knew, contained something that would grab the attention of the police: the photographs of the 10 Muslim men. But he was tired “from hours of continuous interrogations,” he testified. And he was scared things could get worse if he didn’t relent. So he gave up the code. Before that moment, Wa Lone said, “We did not talk about the killings in Inn Din.”

One officer, he told the court, offered “possible negotiations” if Reuters would agree not to publish the story. Wa Lone said he rejected the overture.

His interrogators also berated him for having looked into the killings.

“They said, ‘You are both Buddhists. Why are you writing about ‘kalars’ at a time like this?'” Wa Lone testified, quoting a derogatory Burmese term many use to describe people of South Asian descent, especially Muslims.

Kyaw Soe Oo described coming under similar pressure. At one point, he testified, an interrogator burst into his cell to ask about the photographs of the 10 doomed men from Inn Din: “Why haven’t you told us about this?” the interrogator said. Kyaw Soe Oo said he was then made to kneel on the floor for at least three hours as punishment.

Another time, Kyaw Soe Oo testified, a military intelligence officer brought print-outs of the photos and asked whether he had “sent the photos from my phone to human rights organisations from foreign countries.”

Captain Myint Lwin, the officer in charge of the Yangon police station that conducted the preliminary inquiry after the reporters’ arrests, denied in court that Kyaw Soe Oo was made to kneel during his questioning. He also said that neither reporter was transferred to Aung Tha Pyay interrogation centre. Calls to a police spokesman seeking comment about the reporters’ testimony went unanswered.

When Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo were arrested, their story about the massacre had yet to be completed. Their colleagues Lewis and Slodkowski finished the piece over the following two months. Wa Lone’s wife, Pan Ei Mon, whose pregnancy was advancing while her husband sat in prison, said in an interview that she was against running it. Pan Ei Mon had been speaking with a Myanmar government official who told her he was concerned Wa Lone “would be made an example of”.

The story established that soldiers were among those who killed the Rohingya in Inn Din village, and Pan Ei Mon thought that publishing would shut off any sympathetic channels in the government.

Wa Lone took a different view. He told a Reuters lawyer he wanted the story to run. It appeared in early February.

“After that story was released, I decided not to visit Wa Lone anymore,” Pan Ei Mon said. “I thought all he cared about was his ego – not me or the baby inside me.” The next day, she relented and went to see him.

Wa Lone received other visitors after the story ran. Several senior police officers met him in a room at the prison and videotaped the interview, he testified at his trial. Among the officers, he said, was the brigadier general who, according to earlier court testimony by Capt. Moe Yan Naing, gave the order to set up and arrest the Reuters reporters. The brigadier general asked Wa Lone to reveal the sources for the Inn Din story. Wa Lone said he refused to give up any names.

He and Kyaw Soe Oo have been in jail for 240 days. On April 11 they had yet another court appearance. It was Wa Lone’s 32nd birthday. The day before, the military announced that seven soldiers were sentenced to 10 years in prison with hard labour for participating in the Inn Din massacre. With that, Myanmar’s generals appeared to be acknowledging the truth of Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo’s reporting about the killings in Inn Din.

The tailgate of a police truck opened to let out the police officers guarding Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo. Pan Ei Mon was waiting, brushing her hair back from her face with a wide smile. She was about five months pregnant.

In the passageway where she stood, there was a birthday cake on a chair. The group of more than half a dozen policemen let Wa Lone pause to blow out the candles. He walked into the courtroom grinning.

Inside, the judge declined a motion by the defence to dismiss the case against the reporters. Wa Lone’s wife wept. Kyaw Soe Oo’s wife wept.

On his way out of the courtroom, Wa Lone paused and shouted at the cameras pointing at him. “The culprits who committed the massacre were sentenced to 10 years in prison. However, the ones who reported on it – us – are accused under a law that can get us imprisoned for 14 years,” he said. “So, I’d like to ask the government: Where is the truth? Where is the truth and justice? Where is democracy and freedom?”

The police then led him and Kyaw Soe Oo into the back of the truck. Its tailgate clanged shut. And they were gone.-

>

RELATED STORIES

All photographs, news, editorials, opinions, information, data, others have been taken from the Internet..aseanews.net | [email protected] / For comments, Email to : Aseanews.Net |

All photographs, news, editorials, opinions, information, data, others have been taken from the Internet..aseanews.net | [email protected] / For comments, Email to : Aseanews.Net |