COVID-19: The human vaccine

6 monkeys given an experimental coronavirus vaccine from Oxford did not catch COVID-19 after heavy exposure, raising hopes for a human vaccine

- Monkeys given an experimental vaccine from the University of Oxford appear to have resisted the novel coronavirus.

- Six rhesus macaques given hAdOx1 nCoV-19 in Montana did not fall ill despite heavy exposure, The New York Times reported Monday.

- There is no guarantee the vaccine will work on humans, but successful animal tests are a promising early sign.

- The Oxford Vaccine Group began human trials for the vaccine last week.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Related Video: What Could Be the Fastest Way to End the Coronavirus Crisis?

Six monkeys given a vaccine developed by the University of Oxford are said to be coronavirus-free 28 days after sustained exposure to the virus.

The result is a promising early sign for the vaccine, which is also undergoing human trials. A working human version, however, remains months away even in the best-case scenario.

The monkey experiment was carried out in late March by government scientists at the Rocky Mountain Laboratory in Hamilton, Montana, The New York Times reported Monday.

Six rhesus macaques received a vaccine produced by the Jenner Institute and the Oxford Vaccine Group. They were then exposed to heavy levels of the coronavirus that were known to have previously sickened other monkeys. These monkeys suffered no ill effects, however, and remained healthy at least 28 days later, The Times said.

“The rhesus macaque is pretty much the closest thing we have to humans,” Vincent Munster, the head of the Virus Ecology Unit at the laboratory, told The Times.

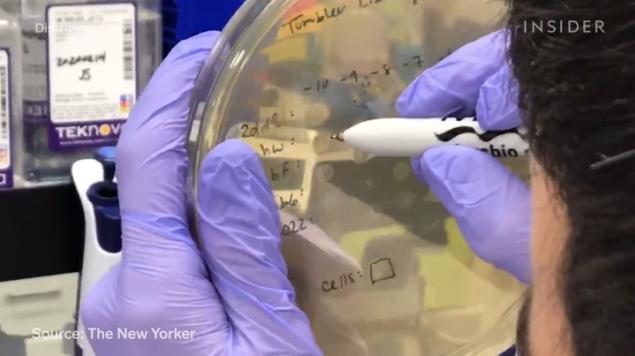

The first human trial of the hAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine from the Oxford Vaccine Group.

YouTube/University of Oxford

The Jenner Institute, working as part of the Oxford Vaccine Group, is leading the global race for a coronavirus vaccine. The UK government has pledged £20 million, or $25 million, to the trial.

The vaccine given to the rhesus macaques is called hAdOx1 nCoV-19. Human trials began Thursday and are expected to be finished in September. The process of developing a vaccine is long, and even having a usable product by September would be unusually fast.

There are more than 70 potential coronavirus vaccines in the works. Here are the top efforts to watch, including the 16 vaccines set to be tested in people this year.

On Monday, the world’s largest vaccine maker, the Serum Institute of India, said it would not wait for the trial to end and was preemptively making 40 million doses to save time in case it worked.

The Serum Bio-Pharma Park in Pune, India.

Serum Institute

Sinovac Biotech, a Beijing-based company, is also hunting for a vaccine to the coronavirus. It found last week that its vaccine also appeared to be effective in macaques. Human trials have now begun.

Humans and macaques share about 93% of their DNA. Just because a vaccine appears to work on a macaque does not mean it will work on humans, however.

Ed Jones/AFP via Getty Images

As many as 80 coronavirus vaccines are in development, but some are choosing to skip the animal-testing stage to save time.

Read the original article on Business Insider.