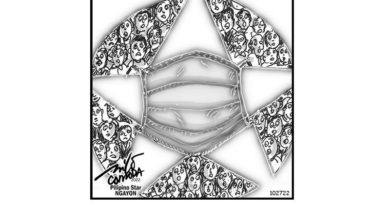

EDITORIAL: Tracing a path to Big Brother?

As the coronavirus pandemic continues to wreak havoc, governments are turning to contact tracing — a tactic used to control outbreaks of syphilis in the 1930s and more recently Ebola in West Africa.

While social-distancing measures and stay-at-home orders played their part in limiting the spread of Covid-19 initially, concerns about a second and third wave of infections, or even the possibility of the virus becoming endemic as predicted by Dr Mike Ryan of the World Health Organization last week have forced governments to brainstorm about how to reopen their economies while keeping public health safety a top priority.

Whereas contact tracing in the past was manual and left a paper trail for the tracers — the people employed to notify those who may have been exposed to the virus — to sort through, the process today is entirely digitised. Governments as well as tech giants Apple and Google are rushing to release tools in the form of mobile apps, programming interfaces to track locations using GPS and Bluetooth technology, and QR systems which feed on personal information. Besides concerns about effectiveness, these systems could potentially alter the future of privacy and redefine basic human rights.

Since contact tracing is information collection, its effectiveness relies on the public’s willingness to participate. Yet, in the US, a little under half of those surveyed by the Kaiser Family Foundation said they would download an app to be notified about potential exposure.

However, contact tracing is well underway in several nations. In China, residents must download a unique health QR code on the WeChat platform by divulging personal information to activate location tracking. The system analyses millions of unique interactions in real-time allowing health authorities to decide who poses no risk and those who must be quarantined by labelling a person’s status as green, yellow, or red — which they must present everywhere they go.

The potential for the misuse of such a system to stifle dissent, or discriminate based on race and religion, is very real and deeply worrying.

In South Korea, hailed for its efforts to flatten the curve quickly, the government is using a mixture of self-reporting, mobile apps, CCTV footage, and credit card transactions for tracing. While South Koreans generally accept these measures, such invasive tactics have had a high price. In recent weeks, the government has divulged sensitive information about potential spreaders such as their visits to love motels and gay nightclubs, activities associated with enormous social stigma locally. Even though the names of the infected were not revealed, savvy internet users were able to identify individuals through breadcrumbs of information. As a result, some South Koreans today are more fearful of the “criticisms and further damage” from being infected than the actual virus itself, according to a poll carried out by Seoul National University.

Closer to home, the Thai government has introduced the “Thai Chana” platform, where shoppers scan a QR code to “check-in” and “check-out” each time they visit a mall, and in future places of work and state offices. Yet, there is no legislation in place to prevent misuse of personal data or hold the handlers to account. A simple glance at the terms and conditions shows customer data can be sent to any organisation by the Public Health Ministry even after disease control measures are lifted.

Saving lives is, and should be, the priority. Yet, in our haste to return some semblance of normality to our daily existence, by granting our government such sweeping surveillance powers we must be careful not to sleepwalk into an Orwellian nightmare of a future.

EDITORIAL

BANGKOK POST EDITORIAL COLUMN

These editorials represent Bangkok Post thoughts about current issues and situations.

Email : [email protected]

SIGN UP TO RECEIVE OUR EMAIL

The most important news of the day about the ASEAN Countries and the world in one email: [email protected]