COVID-19 PANDEMIC: THE CURE-VACCINE- A glimpse into global vaccine race

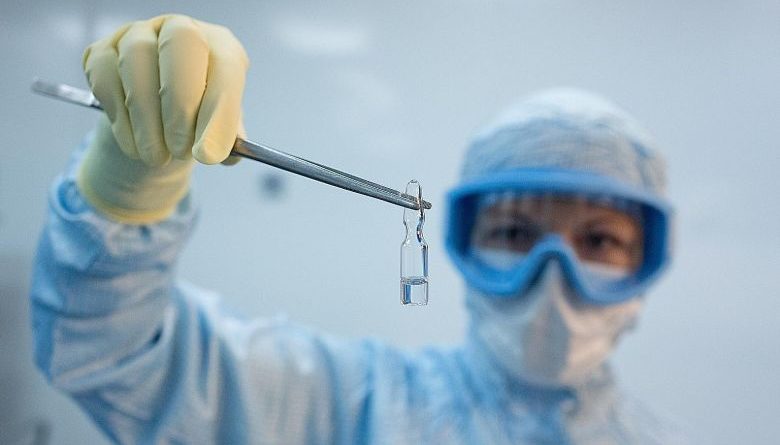

Russia’s “Gam-Covid-Vac” vaccine is among the dozens being developed. Data from the World Health Organisation shows that 31 vaccines are in clinical trials, with another 142 candidate vaccines in pre-clinical evaluation.PHOTO: REUTERS

First is not always best – adequate testing ensures safety and efficacy

The speedy progress of the front runners in the global vaccine race shows that there is a chance for the Covid-19 pandemic to end within two years, as World Health Organisation chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said last week.

However, the haste to come up with a vaccine in the global race may endanger lives if it has not undergone enough testing to make sure it is safe and effective.

And in a crisis where the whole world is affected, a “me first” approach or vaccine nationalism will not help, no matter how tempting it may be, experts have warned.

It has been only about eight months since the Covid-19 outbreak began, but data from the World Health Organisation shows that 31 vaccines are in clinical trials, with another 142 candidate vaccines in pre-clinical evaluation.

.

.

The number could be higher.

Professor Ooi Eng Eong, deputy director of the Duke-NUS Medical School’s emerging infectious diseases programme, said there are already more than 40 vaccine candidates in clinical trials.

The speed is mind-blowing, considering vaccine development is a complex, costly and mammoth task that can take at least five to 10 years.

Among the front runners in the vaccine race are United States-based Moderna Therapeutics and the National Institutes of Health with an mRNA vaccine.

There is also British-Swedish pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford with a vaccine that uses a chimpanzee adenovirus vaccine vector. Adenoviruses are viruses that usually cause the common cold.

Three other candidate vaccines from China and using inactivated vaccines are in phase three trials.

This is the stage when large-scale testing is done to see if the vaccine is safe and effective in tens of thousands of people.

American pharma firm Pfizer is also working on a vaccine with German partner BioNTech, and said it has enrolled more than 11,000 volunteers in its trial.

The type of vaccines may vary among developers but they all trick the body into thinking there is an infection so that it will develop antibodies and immune responses to it.

Singapore’s Duke-NUS Medical School is partnering US pharmaceutical company Arcturus Therapeutics to develop an mRNA vaccine. Clinical trials started here this month.

Prof Ooi said in late June that the soonest the vaccine can be available is about a year later.

“This very optimistic timeline remains unchanged in my mind,” he said. “We are all working as fast but also as thoroughly as we can to test the safety and efficacy of this vaccine candidate.”

Recently, Dr Anthony Fauci, the well-regarded head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in the US, warned against rushing out an untested vaccine. He said one potential danger is that it would be hard for the other vaccines to enrol people in their trials.

.

.

.

.

Professor Teo Yik Ying, dean of the National University of Singapore’s Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, said there is the risk of side effects, including those that may potentially be life-threatening, or actually fail to protect the people against future Covid-19 infections.

“While these may appear to impact only the countries that distribute the unproven vaccine, the worry is one of global vaccine hesitancy and vaccine confidence.”

Prof Teo said it is inevitable that the world will report on the emergence of side effects or safety lapses as a result of taking these unproven vaccines, and this can result in a growing spectre in a segment of the population against any future Covid-19 vaccines.

To be first is not everything. For one thing, experts have said the first vaccine may not be the best, and more effective vaccines may be developed later on.

With so many developers in the race, it is likely that there will be multiple vaccines in the market.

The race also does not end after a vaccine has been proven to be safe and effective in a phase three trial, as there are many hurdles between that and making it available at a clinic. It takes time to scale up production to manufacture billions of doses, and that also depends on the availability of billions of glass vials. Approvals will also need to be secured, and in a timely manner.

Most of the vaccines will be made in the US and Europe. There is the logistical challenge of delivering the vaccines around the world, as most vaccines need to be kept stable at low temperatures.

Clearly, there will not be enough supplies to go around initially, so it is not as if people can make a mad dash for a jab. Experts say decisions will have to be made on which groups will be prioritised.

And then, the vaccines need to be administered.

Prof Teo believes the world is aware that a global distribution of vaccines will realistically happen only next year.

“Even if there is an available supply of safe and effective vaccine for distribution at the end of 2020, it will be to selected groups of people, perhaps even in a small number of countries,” said Prof Teo.

“We do not think that there will be the necessary five billion doses of vaccines available for widespread distribution worldwide by the end of this year.”

Right now, although no Covid-19 vaccines have been proven to be safe and effective, some countries are already vying to secure supplies.

Wealthy countries have struck deals to buy more than two billion doses of vaccine.

For now, as the world draws closer to the possibility of having a successful vaccine, the rush to get countries to cooperate becomes more urgent. Vaccine experts say it is only with global cooperation that the world can improve the chances of developing a vaccine and ensuring it is distributed equitably.

.

Sign up for our daily updates here and get the latest news delivered to your inbox.

Get The Straits Times app and receive breaking news alerts and more.