CALIFORNIA: How a scrappy Chicano from L.A. came to own a Scottish castle

How a scrappy Chicano from L.A. came to own a Scottish castle

In a 16th century Scottish castle, the overbearing Los Angeles Chicano who rarely says his name without attaching the appellation “the trillion-dollar man” is berating 24 students, each of whom paid $30,000 for the privilege.

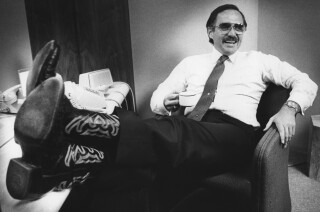

Dan Peña, who turns 76 this year but remains a commanding presence at 6-foot-1, erupts into an expletive-infested lecture that careens between withering insults and strategies to become like him — successful in business and in life. Quoting him requires lots of bleeping.

“You, you in this room,” he begins in a videotaped lesson, “you’re taking your [bleeping] foot off the accelerator instead of pushing the gas pedal through the [bleeping] floorboard!”

“And we all know why; it’s easier,” Peña adds, shaking his head in exasperation, “and it’s hard to admit you have no [bleeping] self-esteem.”

With supreme confidence and politically incorrect bluster, Peña prods and pokes his students to transform them into hardworking entrepreneurs with skin as tough as rhino hide beneath tailored business suits.

It’s not lost on his students that the location — Guthrie Castle, in the golfing heartland of Angus, Scotland — is not a conference center. It’s his home, and when he’s not delivering blistering lectures, the graying Peña lives a relatively quiet Scottish-laird existence.

It’s all so improbable. Peña seemed bound for failure through his difficult youth in East Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley until he did something Americans do best. He reinvented himself.

Peña would reap a fortune in the oil industry and develop a sharply opinionated conservative nature that reflects not merely his gotta-keep-busy-to-get-rich personality, but also his us-against-them contempt for “sniveling, lazy, entitled and easily offended types who long for public approval and run for the hills when things get rough.”

Not many outside of the oil industry knew his name until 1983, when Peña was featured in a Times story about a tiny number of Chicanos de oro, wealthy Mexican Americans on their way to megafortunes.

“Peña is a dream of ethnic alchemy,” columnist Al Martinez wrote in the article that was part of a Pulitzer-winning series on Latinos. “Tough, smart and demanding to be heard — even his quick, flashing smile is noisy — Peña seemed destined to be rich.”

At that time, Peña was bidding to buy a refinery and petroleum terminal.

“If the oil refinery deal goes through,” he said, “I could either be rich beyond belief or lose everything. But you’ve got to dare. I won’t be picked on. I’m not a victim of the sombrero syndrome. Don’t try walking on Dan Peña.”

The man who would own a castle started life in a modest wood-framed house in a barrio just north of downtown.

His mother, Amy, of Austrian and Spanish descent, was from Mexico, and gave her son blue eyes. His father, Manuel, who was from New Mexico, wore pistols in leather holsters, one on each hip, and became one of the first Mexican American detectives in the Los Angeles Police Department.

Times staff writer Louis Sahagun discusses being successful in business and in life with entrepreneur Dan Pena.

“When Chicago mobsters came to town back in the 1940s, my father and other guys would meet them at the train station,” Peña recalled. “Then they took them up to the Hollywood Hills, where some were severely beaten.”

It is said that Manny killed 11 people in the line of duty and was prone to take the law into his own hands.

(The senior Peña later left the LAPD to work with a secret unit of the CIA, according to Peña and historians. He oversaw an investigation into the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy in Los Angeles and personally controlled the classification and use of every bit of evidence collected.)

“My father was a cold and brutal man,” Peña says, “and I was out of control as a kid. In grammar school, I tried to drop an aquarium on a teacher’s head from a second-story window. But by the grace of God, he moved. It hit him on the shoulder and dislocated his collarbone.”

His family moved to upper-class Encino when he was 10 so that he would be raised among high achievers.

Peña insists that his path to success, power and money started in grammar school, when he was forced to wear a dunce hat.

When he got home, Peña said, “my father beat the hell out of me for getting in trouble at school.”

To hear Peña tell it, all the scolding “made me tougher.”

His teenage years went by in an alcoholic haze punctuated by run-ins with the law. Relatives joked, “If Danny ever focuses all that anger on a career, he’ll be a multimillionaire.”

They were right.

Peña traces his desire to make money to an Army hitch in Europe, where he saw American tourists flashing rolls of cash, staying in posh hotels and dining in four-star restaurants.

After leaving the Army as a 2nd lieutenant, he earned his bachelor’s degree in business administration at Cal State Northridge and took a job with a real estate investment company in 1971. By year’s end, he had been appointed sales manager with a six-figure salary and had cleaned out the department by firing 50 salesmen — a job he said had to be done. It earned him the name “Hatchet Man.”

When that company failed, Peña became a stockbroker, and then a financial planner. At 26, he replaced his Volkswagen with a Rolls-Royce.

He began looking at oil in 1982, when a friend became rich on soaring petroleum prices. Within months — driving himself “like a wild-eyed madman” — he founded Great Western Resources Inc., a Houston-based energy company, with an investment of $820 — and a bravado that made some competitors want to see him crushed.

A decade later, he was Great Western’s chairman, president and chief executive, presiding over a company with $450 million in market capital.

He was already living in unapologetic opulence — vacations at European resorts, chauffeured Mercedes limousines, alligator-skin cowboy boots — when he was perusing a magazine featuring luxury-lifestyle products. He had just finished a routine 10-mile run near his home in Palos Verdes when he spotted “an ad for a castle in Scotland that was up for sale.”

“I knew from my Wall Street days that if you wanted to do business with financial institutions, you had to prove to them that you didn’t need their services,” he suggested in a tip sheet titled “33 Secrets for Success.” “So, the castle was to become the perception which would cause the business community to realize that we didn’t need their help since we had already arrived, which, of course, we hadn’t.”

He was unprepared, however, for the responsibilities that came with a 450-year-old castle.

“Something breaks down every five minutes around here!” he groused in one of several interviews over Zoom. “It costs about $100,000 a month to maintain this estate because this place eats money!

“I’ve got broken pipes, ceilings falling down, wallpaper peeling — and a rug that’s been on the game room floor for 300 years!”

But maintaining the estate “has meant employment for locals and work for local businesses,” said the Rev. Brian Ramsay, minister of nearby Guthrie Parish Presbyterian Church, and a neighbor of Peña’s for more than three decades.

Peña supports local charities as well, but keeps it quiet. “During the present pandemic, for example,” Ramsay said, “he provided PPE and sanitizing for local volunteers and very generous donations to food banks in the Angus area.”

On a personal level, Peña “is always completely honest, which is both refreshing and sometimes challenging,” he added. “He is not one to mince his words nor suffer fools gladly, but I have also seen glimpses of deep affection for those he loves and a strong sense of justice, which show the depth of his personality.

”A most interesting character, indeed.”

That no-holds-barred personality also contributed to his departure from Great Western in 1992, when he was ousted by the board of directors. To hear Peña tell it, they were fed up with his flashy lifestyle and penchant for discussing controversial corporate matters with the press.

Beyond that, the company’s stock price had plummeted during the Persian Gulf War. Rumors had floated that the company’s largest investor, the Kuwaiti Investment Office, needed cash and was preparing to dump Great Western to get it.

“The board members complained that I should have known that Iraqi forces were going to invade Kuwait in 1990,” Peña said. “Hell, man, the CIA didn’t even know that was going to happen.”

Peña sued Great Western for breach of contract, among other accusations. Great Western countersued, alleging mismanagement, breach of fiduciary duty and negligence.

A Houston jury in 1993 rejected Great Western’s claims and enforced Peña’s roughly $5-million golden parachute.

Then Peña reinvented himself. Again.

This time, it meant conducting business philosophy courses, what he calls the Quantum Leap Advantage, at Guthrie Castle.

Peña maintains that he could not care less that a lot of people are offended by his views and teaching style.

“I only have three regrets in life,” he says, without significant remorse. “I’m a combat-trained Army officer who never saw combat. I didn’t set my goals high enough — former Texas Gov. John Connally once said I should have been the first Mexican American president. And one night when my mother was ill and afraid that she was dying, I yelled at her, ‘God damn it, mom, stop crying! You’re not going to die!’ She died the next morning.”

It sounds contrived at times. Some former students have accused Peña of luring vulnerable customers with false promises of profit and success.

But Peña’s acolytes often speak of him in nearly messianic tones. His “trillion-dollar man” moniker, he says, refers to the wealth amassed by his students.

“Driving onto the castle grounds for the first time was like approaching an energy of greatness,” said Dustin Plantholt, a documentarian who recently completed a film about Peña.

“True, some people get very emotional when he looks them in the eyes and screams, ‘You’re a wuss; a disgusting [bleeping] crybaby,’” Plantholt said. “Eventually they realize that he’s drilling into their weak sides so that they can toughen up and start to stand up for themselves.”

Among Peña’s first students was Ruben Navarrette, a journalist and Harvard graduate who, as he puts, “did not go on to make billions of dollars.”

“My wife says I worship the ground Dan walks on — and she’s probably right,” Navarrette said with a laugh. “He is a wise, old, world-class teacher who can turn an ordinary person into someone extraordinary.”

Then there is Hector Padilla, 46, a former police officer turned real estate broker who was already worth $5 million when he took Peña’s program in 2015.

Padilla, president of HP Capital Investments Inc. in Inglewood, was only half kidding when he said, “People go to Dan when they need an ass-whipping more than a hug. And, like many others who made it through his program, I have a love-hate relationship with him.”

“I sent him an email after I bought my first Rolls-Royce,” he recalled. “His response: Good for you, pendejo [dumbass]. You can do better than that.”

Peña recalled that he drove his Rolls-Royce to Lincoln High School, hoping to inspire the students, “and the kids there didn’t give a [bleep].”

He maintains L.A. ties — his brother, Vincent Peña, 61, is deputy chief of the Los Angeles County Fire Department — and has a cabdriver’s memory of Southern California’s streets and districts.

Peña’s legacy projects include an athletic scholarship at Lincoln High. A year ago, he added $100,000 to the reward offered for information on the wounding of two sheriff’s deputies shot in Compton.

Given the pandemic and hip and knee replacements, he spends most of his time at his castle. He relishes the warm memory of when his father came to Scotland.

“My father came to visit me at the castle,” Peña recalled. “Looking up in awe at the crystal chandeliers hanging from a vaulted ceiling, he shook his head and sighed, ‘C’mon, Danny, tell me this isn’t from drug money.’”

“Nope,” Peña replied. “Just oil and stocks.”

Then they were off on a grand tour of the castle and its treasures, including a wine cellar featuring a bottle of 60-year-old Macallan scotch that cost Peña $14,000.

Then there’s the huge oil painting in a gilded frame that Peña had commissioned: It’s a strapping Scottish nobleman — albeit with an unusually dark complexion — on the heath with a stalwart hunting hound at his side.

“That’s me,” Peña said with a smile. “I’m a Mexican American in a Scottish castle. But around here, people treat me as an American rich guy.”

The perils of parenting through a pandemic

What’s going on with school? What do kids need? Get 8 to 3, a newsletter dedicated to the questions that keep California families up at night.

.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.