TOURISM: CALIFORNIA: You know their names: Palos Verdes, La Brea, Sepulveda. But what were the ranchos?

Not even in Los Angeles was the land just a blank slate waiting for the arrival of swimming pools and movie stars.

You know this, yet you may not even realize that you do.

You recognize the names of some of the vast, vanished ranchos that have marked the maps of Southern California for a couple of centuries. The word “rancho” got snipped off along the way, but you know them as Palos Verdes, San Pedro, La Brea and Centinela, San Vicente and Santa Anita. The men who were granted these lands you know, too — names like Verdugo, Sepulveda, Dominguez.

What is astounding is that down to this day, the footprints of these ranchos are still often the same footprints of our modern cities and streets and landmarks.

Philip J. Ethington is a professor of history, political science and spatial science at USC. I asked him what he sees when he drives around 21st century Los Angeles, through the masks of centuries and millennia.

He sees ghosts.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

“I see many layers. There’s a very deep history of civilization here. As you drive along Pico [Boulevard], it looks like an undifferentiated landscape. But you’re going through ecologies that supported [Native American] communities for eight or nine thousand years. I see the oak groves that used to be there.”

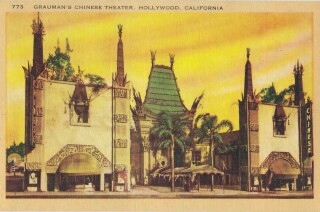

Today’s L.A. map might be passingly familiar to the rancheros of 200 years ago. Many of their rancho boundaries are still the boundaries of massive modern real estate parcels, Ethington says, and in Los Angeles County, “about 173 miles of roadway coincide with former rancho boundaries — and 87 miles of municipal roadways.” No wonder “Ghost Metropolis” is the name of his forthcoming book.

The L.A. you live in today was first stamped and shaped by Native Americans, and then, millennia later, by the fabled ranchos, back when virtually all of Southern California — stupendous hunks of land, measured in “leagues,” miles times miles — was in the hands of a handful of families, an aristocracy of acreage.

When people speak of California’s “Spanish land grants,” they probably conjure a scene from an MGM costume epic: a dour monarch in a goatee and velvet pants, stamping molten red wax with a royal seal the size of a salad plate.

It was nothing like that.

Beginning in the late 1700s, the power to give away “Alta California” land lay with its governors like Pedro Fages, who came here with the first expeditions. He gave early grazing and settling rights to three of his army comrades, called “soldados de cuera” for their boiled-leather uniform jackets: Jose Maria Verdugo, Juan Jose Dominguez and Manuel Nieto.

.

In time the ranchos became like little kingdoms, but at first they were pretty rudimentary operations: build a modest adobe house and outbuildings, and turn the cattle loose to graze.

In the early decades of the 20th century, before subdivisions became our richest crop, Los Angeles County was a cornucopia, the single most profitable agricultural county in all of the United States.

But a hundred years and more before then, the money was in cattle, and cattle need a lot of land. Once a year, the ranchos rounded them up, slaughtered them, and sold the tallow and hides to the Yankee trading ships hovering off the coast.

“California dollars” is what Yankees called the hides, and the seaman and author Richard Henry Dana wrote of San Pedro as the “hell of California,” for the toil it took to get the ranchos’ goods over the coastline’s rocks and ridges and onto the ships, which carried the hides to New England’s cobblers to turn into shoes.

What’s notable but not really surprising about the ranchos, Ethington points out, is how closely they tracked the lands of the Native Americans they displaced.

“The Indigenous villages had thousands of years to settle onto the very best town sites, best access to water, best elevation, best views, best oak groves, so obviously the Spanish came in and took them. They became the center points of the ranchos; those were the most desirable places to settle.”

“You can think of the [modern] municipalities as built on the ranchos, and the ranchos as built on the Tongva villages.”

And the rancho system itself “just continued the hacienda system of the Spanish, which was a model actually Roman in origin: huge farms you grant to the conquerors, and also gave them the rights to the labor of the people who lived there.”

.

EXPLAINING L.A. WITH PATT MORRISON

What do you want to know about L.A.?

This week’s column was sparked by a reader question: “Can you explain the old rancho system that eventually became current-day South Bay?” South Bay and then some! Tell Patt what you’d like to know more about.

In California, that labor was usually “Christianized” Native Americans tied almost like serfs to the ranchos and before that to missions, where the Catholic fathers, Ethington says, “ran essentially these giant labor camps.”

The pace of California land grants picked up considerably after Mexico gave Spain the boot in 1821. More than 90% of what people think of as Spanish grants were made after that. Mexico bestowed full ownership along with grazing rights, and just like in the United States, giveaway land was an enticement to bring settlers to howling wilderness.

Things took a very Tudor turn in 1832, when Mexico secularized California’s Catholic missions. At least half of the mission land and livestock was supposed to have been handed back to the Native Americans who worked it and who had owned it in the first place.

But what Ethington calls the “magic moment” for it passed. The governor who pledged to do it died unexpectedly, and his successors blew it off.

Like Henry VIII, who abolished monasteries and abbeys in Tudor England and gave away or sold off those lands and riches, political insiders or operators came away with the lion’s share, and the Native Americans ended up with virtually none of what they were supposed to get.

So many Native Americans, now homeless as well as landless, ended up working the old lands with new masters — the rancheros.

These ranchos were an economic and political system unto themselves. By 1846, says the 1939 book “Ranchos Become Cities,” “ranchos extended from the San Diego County area in the south to the Shasta County area in the north.”

This is the “old California” image that caught the nation’s fancy: haciendas, grandees in silver- and gold-trimmed clothes, riding costly horses and betting fortunes on a card.

.

These brief decades were glamorized by a huge bestseller, an 1884 novel called “Ramona,” by Helen Hunt Jackson, who had been a guest at one of the great haciendas. The book, a romance of thwarted, mixed-race Native American lovers, brought hundreds of trainloads of sentimental tourists and settlers to their imagined California.

Then where did these great possessions of land go? The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ending the Mexican-American War in 1848 guaranteed existing Mexican land rights — if they could be proven.

Alas for the landowners, “Spanish and Mexican grants were pretty sketchy in how they were described,” says Ethington, in hand-drawn diseño maps that could say the property “runs from the edge of the river to this boulder to an oak tree. Some are like chicken scratches, but some are gorgeous.” One description of Rancho San Pedro’s boundaries said they commenced “near some sunken barrels.”

The United States, on the other hand, set great store by measuring every yard of land. Before he was a general or a president, George Washington was a surveyor.

Some Mexican land grants were confirmed right away by American land “patents.” Others took decades to certify, and some never were granted at all.

How else did these kingdoms slip away?

It’s kind of soap-opera-ish, really — marriages and rivalries and bankruptcies and disputed wills.

As someone once pointed out, the great Californio families were uncommonly blessed with daughters, and these daughters sometimes married ambitious Yankees and took family land with them.

John Temple — of Temple Street fame in downtown L.A. — married a daughter of the Los Cerritos rancho owner, and bought out her siblings’ claims for $3,000.

Massachusetts go-getter Abel Stearns married the glamorous socialite heiress and philanthropist Arcadia Bandini when she was 14. Widowed at 55, she married another Yankee, Robert Baker, who had bought more than 38,000 acres of the Rancho San Vicente and Santa Monica from the Sepulveda family for $54,000 in 1872.

Like Stearns, he too left it all to Arcadia when he died. She became known as the “godmother of Santa Monica,” but when she died in 1912, without heirs or a will, the battle for her estate was legendary.

Some cash-strapped Californio dons took out mortgages with vicious terms — as high as 6% monthly interest. The droughts of the 1860s savaged the cattle business, and Julio Verdugo lost most of his part of Rancho San Rafael at auction in 1869, after a $3,500 mortgage rose to an impossible $59,000 with the interest.

Several generations of the pioneering Bixby family bought up mega-acreage; by one decree, it obtained land that includes 14 miles of coastline at the Palos Verdes Peninsula. At least 10 cities, Long Beach chief among them, would arise on Bixby land.

The survival of monster chunks of rancho land made 20th century Los Angeles what it became, an easy place for the new and immense citrus industry to flourish, and for the enormous tract developments that to this day we call home.