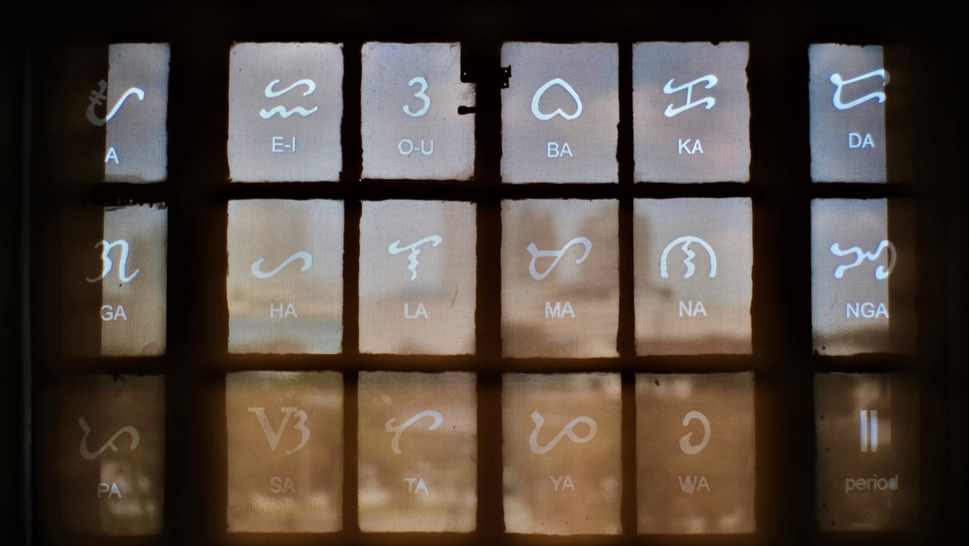

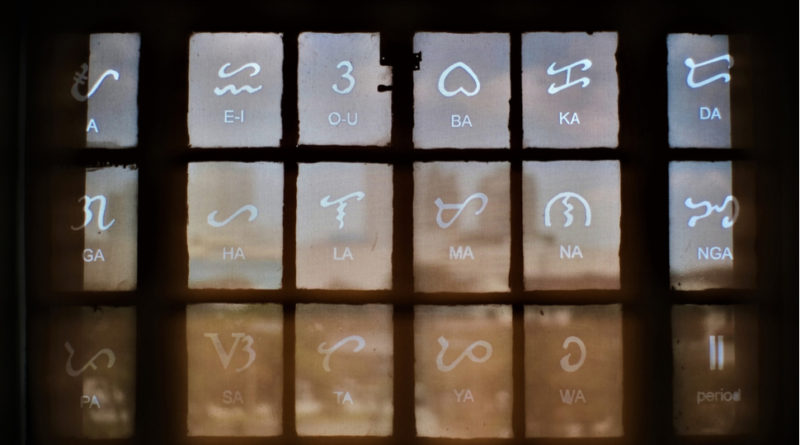

Philippines Heritage-History | These Precolonial Filipino Words Recorded by Pigafetta Are Still Used Today

‘Words of those heathen people,’ Pigafetta wrote.

Five hundred years ago, Antonio Pigafetta preserved snapshots of the lives and culture of the precolonial Filipinos. Pigafetta was an Italian scholar and explorer who chronicled the first circumnavigation of the world led by Ferdinand Magellan.

The voyage was so significant because, finally, it proved the world was not flat and suggested that maybe, the Earth wasn’t the center of the universe, after all.

But it also led to other misconceptions: Filipinos are heathens who played a violin with copper strings. At least that’s what Pigafetta wrote.

After the death of Magellan at Mactan, Pigafetta had some time to record the words used by the locals from Cebu. The prolific chronicler also described the island:

In that island are found dogs, cats, rice, millet, panicum, sorgo, ginger, figs (bananas), oranges, lemons, sugarcane, garlic, honey, cocoanuts, nangcas, gourds, flesh of many kinds, palm wine, and gold.

It is a large island, and has a good port with two entrances—one to the west and the other to the east northeast. It lies in x degrees of latitude toward the Arctic Pole, and in a longitude of one hundred and sixty-four degrees from the line of demarcation. Its name is Zubu (Cebu). We heard of Malucho there before the death of the captain-general. Those people play a violin with copper strings.

In his observations, he noted that precolonial Filipinos knew how to count. He also noted that the locals were sophisticated enough to comb their hair (they had a tool for that), and that they had actual words for the different parts of their body.

Interestingly, most of these precolonial Filipino words recorded by Pigafetta are still in use today.

In his book, Primo viaggio intorno al mondo, (First Voyage Around the World), he takes care to record as many Filipino words as he can. Disparagingly, or perhaps because of his Eurocentric sense of superiority, he wrote:

“Vocabuli de questi populi gentili.” Which is loosely translated as, “Words of those heathen people.”

The following are the Visayan words Pigafetta transcribed 500 years ago, most of which are still used today.

for man: lac

for woman: paranpaon

for young woman: beni beni

for married woman: babay

for Hair: boho

for face: guay

for eyelids: pilac

for eyebrows: chilei

for eye: matta

for nose: ilon

for jaws: apin

for lips: olol

for mouth: baba

for teeth: nipin

for gums: leghex

for tongue: dilla

for ears: delengan

for throat: liogh

for neck: tangip

for chin: queilan

for beard: bonghot

for shoulders: bagha

for spine: licud

for breast: dughan

for body: tiam

For armpit: ilot

for arm: botchen

for elbow: sico

for pulse: molanghai

for hand: camat

for the palm of the hand: palan

for finger: dudlo

for fingernail: coco

for navel: pusut

for penis: utin

for testicles: boto

for vagina: billat

for to have communication with women: jiam

for buttocks: samput

for thigh: paha

for knee: tuhud

for shin: bassag bassag

for calf of the leg: bitis

for ankle: bolbol

for heel: tiochid

for sole of the foot: lapa lapa

for gold: balaoan

for silver: pilla

for brass: concach

for iron: butan

for sugarcane: tube

for spoon: gandan

for rice: bughax baras

for honey: deghex

for wax: talho

for salt: acin

for wine: tuba, nio, nipa

for to drink: minuncubil

for to eat: macan

for hog: babui

for goat: candin

for chicken: monoch

for millet: humas

for sorgo: batat

for panicum: dana

for pepper: manissa

for cloves: chianche

for cinnamon: mana

for ginger: luia

for garlic: laxuna

for oranges: acsua

for egg: silog

for cocoanut: lubi

for vinegar: zlucha

for water: tubin

for fire: clayo

for smoke: assu

for to blow: tigban

for balances: tinban

for weight: tahil

for pearl: mutiara

for mother of pearl: tipay

for pipe [a musical instrument]: sub in

for disease of St. Job: alupalan

bring me: palatin comorica

for certain rice cakes: tinapai

good: main

no: tidale

for knife: capol, sundan

for scissors: catle

to shave: chunthinch

for a well-adorned man: pixao

for linen: balandan

for the cloth with which they cover themselves: abaca

for hawk’s bell: coloncolon

for pater nosters of all classes: tacle

for comb: cutlei, missamis

for to comb: monssughud

for shirt: abun

for sewing-needle: daghu

for to sew: mamis

for porcelain: mobuluc

for dog: aian, ydo

for cat: epos

for their scarfs: gapas

for glass beads: balus

come here: marica

for house: ilaga, balai

for timber: tatamue

for the mats on which they sleep: tagichan

for palm-mats: bani

for their leaf cushions: uliman

for Wooden platters: dulan

for their god: Abba

for sun: adlo

for moon: songhot

for star: bolan, bunthun

CONTINUE READING BELOW

for dawn: mene

for morning: uema

for cup: tagha

large: bassal

for bow: bossugh

for arrow: oghon

for shields: calassan

for quilted garments used for fighting: baluti

for their daggers: calix, baladao

for their cutlasses: campilan

for spear: bancan

for like: tuan

for figs [i.e., bananas]: saghin

for gourds: baghin

for the cords of their violins: gotzap

for river: tau

for Fishing-net: pucat, laia

for small boat : ampan

for large canes: cauaghan

for the small ones: bonbon

for their large Boats: balanghai

for their small Boats: boloto

for crabs: cuban

for fish: icam, yssida

for a fish that is all colored panapsapan for another red [fish]: timuan

for a certain other [kind of fish]: pilax

for another [kind of fish]: emaluan

all the same: siama siama

for a slave: bonsul

for gallows: bolle

for ship: benaoa

for a king or captain-general: raia

Numbers

one: uzza

two: dua

three: tolo

four: upat

five: lima

six: onom

seven: pitto

eight: gualu

nine: ciam

ten: polo

Source: Primo viaggio intorno al mondo (1519–1522), by Antonio Pigafetta.

.

TRIVIA

Antonio Pigafetta

|

Antonio Pigafetta

|

|

|---|---|

Statue in Cebu City in the Philippines

|

|

| Born | between 1480 and 1491 |

| Died | c. 1531 (aged around 40–50)

Vicenza, Republic of Venice

|

| Nationality | Venetian |

| Years active | 1500s–20s |

| Known for | Chronicling Magellan’s circumnavigation |

Antonio Pigafetta (Italian: [anˈtɔːnjo piɡaˈfetta]; c. 1491 – c. 1531) was an Venetian scholar and explorer. He joined the expedition to the Spice Islands led by explorer Ferdinand Magellan under the flag of the emperor Charles V and after Magellan’s death in the Philippine Islands, the subsequent voyage around the world. During the expedition, he served as Magellan’s assistant and kept an accurate journal, which later assisted him in translating the Cebuano language. It is the first recorded document concerning the language.

Pigafetta was one of the 18 men who made the complete trip, returning to Spain in 1522, under the command of Juan Sebastián Elcano, out of the approximately 240 who set out three years earlier. These men completed the first circumnavigation of the world. Others mutinied and returned in the first year. Pigafetta’s surviving journal is the source for much of what is known about Magellan and Elcano’s voyage.

At least one warship of the Italian Navy, a destroyer of the Navigatori class, was named after him in 1931.

.

Early life

Pigafetta’s exact year of birth is not known, with estimates ranging between 1480 and 1491. A birth year of 1491 would have made him around 30 years old during Magellan’s expedition, which historians have considered more probable than an age close to 40.[1] Pigafetta belonged to a rich family from the city of Vicenza in northeast Italy. In his youth he studied astronomy, geography and cartography. He then served on board the ships of the Knights of Rhodes at the beginning of the 16th century. Until 1519, he accompanied the papal nuncio, Monsignor Francesco Chieregati, to Spain.[2]

Voyage around the world

Map of Borneo by Pigafetta.

Nao Victoria, Magellan’s boat Replica in Punta Arenas

In Seville, Pigafetta heard of Magellan’s planned expedition and decided to join, accepting the title of supernumerary (that exceeds the number) and a modest salary of 1,000 maravedís.[3] During the voyage, which started in August 1519, Pigafetta collected extensive data concerning the geography, climate, flora, fauna and the native inhabitants of the places that the expedition visited. His meticulous notes proved valuable to future explorers and cartographers, mainly due to his inclusion of nautical and linguistic data, and also to latter-day historians because of its vivid, detailed style. The only other sailor to maintain a journal during the voyage was Francisco Albo, Victoria‘s last pilot, who kept a formal logbook.

Return

Casa Pigafetta, his palace in Vicenza.

Pigafetta was wounded on Mactan in the Philippines, where Magellan was killed in the Battle of Mactan in April 1521. Nevertheless, he recovered and was among the 18 who accompanied Juan Sebastián Elcano on board the Victoria on the return voyage to Spain.

Upon reaching port in Sanlúcar de Barrameda in the modern Province of Cadiz in September 1522, three years after his departure, Pigafetta returned to the Republic of Venice. He related his experiences in the “Report on the First Voyage Around the World” (Italian: Relazione del primo viaggio intorno al mondo), which was composed in Italian and was distributed to European monarchs in handwritten form before it was eventually published by Italian historian Giovanni Battista Ramusio in 1550–59. The account centers on the events in the Mariana Islands and the Philippines, although it included several maps of other areas as well, including the first known use of the word “Pacific Ocean” (Oceano Pacifico) on a map.[3] The original document was not preserved.

However, it was not through Pigafetta’s writings that Europeans first learned of the circumnavigation of the globe. Rather, it was through an account written by a Flanders-based writer Maximilianus Transylvanus, which was published in 1523. Transylvanus had been instructed to interview some of the survivors of the voyage when Magellan’s surviving ship, Victoria, returned to Spain in September 1522 under the command of Juan Sebastian Elcano. After Magellan and Elcano’s voyage, Pigafetta utilized the connections he had made prior to the voyage with the Knights of Rhodes to achieve membership in the order.

The Relazione del primo viaggio intorno al mondo

Antonio Pigafetta also wrote a book, in which a detailed account of the voyage was given. It is quite unclear when it was first published and what language had been used in the first edition. The remaining sources of his voyage were extensively studied by Italian archivist Andrea da Mosto, who wrote a critical study of Pigafetta’s book in 1898 (Il primo viaggio intorno al globo di Antonio Pigafetta e le sue regole sull’arte del navigare[4]) and whose conclusions were later confirmed by J. Dénucé.[5]

Today, three printed books and four manuscripts survive. One of the three books is in French, while the remaining two are in the Italian language. Of the four manuscripts, three are in French (two stored in the Bibliothèque nationale de France and one in Cheltenham), and one in Italian.[5]

From a philological point of view, the French editions seem to derive from an Italian original version, while the remaining Italian editions seem to derive from a French original version. Because of this, it remains quite unclear whether the original version of Pigafetta’s manuscript was in French or Italian, though it was probably in Italian.[5] The most complete manuscript, and the one that is supposed to be more closely related to the original manuscript, is the one found by Carlo Amoretti inside the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan and published in 1800 (Primo viaggio intorno al globo terraqueo, ossia ragguaglio della navigazione alle Indie Orientali per la via d’Occidente fatta dal cavaliere Antonio Pigafetta patrizio vicentino, sulla squadra del capitano Magaglianes negli anni 1519-1522). Unfortunately, Amoretti, in his printed edition, modified many words and sentences whose meaning was uncertain (the original manuscript contained many words in Veneto dialect and some Spanish words). The modified version published by Amoretti was then translated into other languages carrying into them Amoretti’s edits. Andrea da Mosto critically analyzed the original version stored in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana and published this rigorous version of Pigafetta’s book in 1894.[4]

Regarding the French versions of Pigafetta’s book, J. Dénucé extensively studied them and published a critical edition.[6]

At the end of his book, Pigafetta stated that he had given a copy to Charles V. Pigafetta’s close friend, Francesco Chiericati, also stated that he had received a copy and it is thought[by whom?] that the regent of France may have received a copy of the latter. It has been argued that the copy Pigafetta had provided may have been merely a short version or a draft. It was in response to a request, in January 1523, of the Marquis of Mantua that Pigafetta wrote his detailed account of the voyage.[5]

Works[edit]

Antonio Pigafetta wrote at least two books, both of which have survived:

- Relazione del primo viaggio intorno al mondo (1524-1525);

- Regole sull’arte del navigare (1524-1525) (contained in Andrea Da Mosto, ed. (1894). Il primo viaggio intorno al globo di Antonio Pigafetta e le sue regole sull’arte del navigare.).

Exhibition

In June 2019, in the context of the quincentenary of the circumnavigation, an exhibition entitled Pigafetta: cronista de la primera vuelta al mundo Magallanes Elcano opened in Madrid at the library of the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID). AECID was also involved in the publication of a book about the expedition La vuelta al mundo de Magallanes-Elcano : la aventura imposible, 1519-1522 (ISBN 978-84-9091-386-4).[7]

Ads by:

Memento Maxima Digital Marketing

@[email protected]

SPACE RESERVE FOR ADVERTISEMENT

Memento Maxima Digital Marketing @

Memento Maxima Digital Marketing @