CHESS | WHY Chess Grand Master Magnus Carlsen refused to defend his World Champion Title ?

How Magnus Carlsen went from the world’s best chess player to refusing to defend his title after losing motivation with the game

- Magnus Carlsen was 13 when he became a Grandmaster and 19 when he became the youngest ever world No. 1.

- He won five world championships, modeled for G-Star, was offered a role in Star Trek, and made millions of dollars.

- He’s considered the first proper chess superstar since Bobby Fischer, but in 2022, he said he would not defend his title.

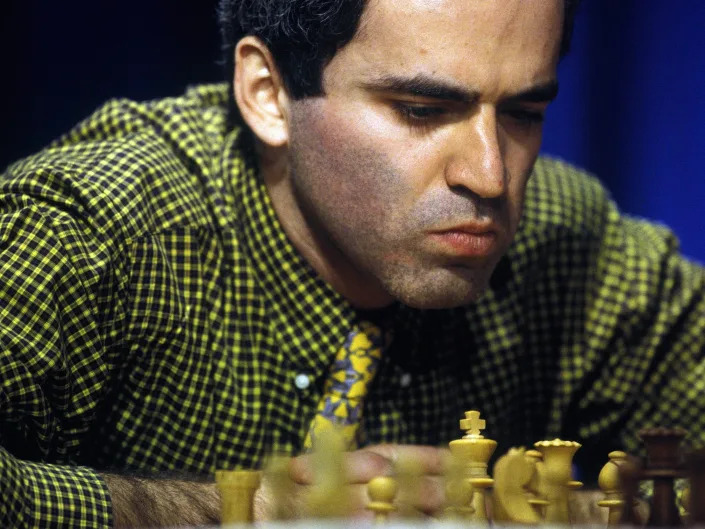

Magnus Carlsen

Norwegian chess player

Magnus Carlsen once said the first line of his autobiography would be: “I am not a genius.”

Regardless of whether he is a genius, Carlsen is certainly remarkable. He’s been the world’s best chess player for the last 10 years. He became a chess Grandmaster at 13, then the youngest player to ever rank number 1 in the world at 19. He’s won five world championships.

According to the Elo rating system, which has ranked chess players by their estimated strength for a century, he’s the best ever.

But in 2022, he announced he would not be defending his title. He said he wasn’t motivated and that he didn’t have a lot to gain.

Magnus Carlsen was born in Norway on November 30, 1990. When he was 2, he was completing 50-piece puzzles. By 4, he was memorizing countries and population sizes across the world. By 5, he was spending hours playing with Legos.

“He had the ability to sit for a very long time, even when he was small,” his mother Sigrun told The Wall Street Journal.

Sources: Guardian, CNN, New Yorker, Wall Street Journal

He didn’t start playing until he was 8 years old. His father Henrik tried to get him into it when he was 5 but failed to captivate him.

“Well, some people can really focus on chess at a much earlier age, even 4 or 5 years old, but I couldn’t,” Carlsen told The Guardian. “Age 8 was the right time for me.”

Carlsen got interested in the game when his older sister started playing properly because he wanted to beat her. At first, Henrik only used one piece against Carlsen’s complete set.

.

Every time Carlsen beat his dad, Henrik got to add a piece, making it increasingly difficult to beat him.

Sources: New Yorker, CNN, New York Times, Guardian

Carlsen quickly began to prioritize chess over everything else, including school. At dinner, he had a second table set up beside the main table with a chessboard on it. He spent five hours each night playing.

Source: Guardian

Within a year, he had beaten his father in blitz chess where each player only has five minutes to play. Soon after, he entered local competitions.

In 2000, when he was 9 years old, Carlsen took classes with former Norwegian junior champion Torbjorn Ringdal Hansen.

In 2001, he started taking classes under Norwegian Grandmaster Simen Agdestein, who tutored him over the next four years.

Agdestein told the New Yorker he was the “best natural player” he had ever seen.

Source: New Yorker

Carlsen played all of the time. He told The Guardian it wasn’t an accident he became Norway’s best chess player.

He said his peers treated it like a hobby. But for him, he said it was “something I wanted to do every day, so it was only natural that I surpassed them.”

“How I managed to take the next steps rather than others, I cannot tell you,” he said.

Source: Guardian

In 2004, when he was 13, The Washington Post dubbed him the “Mozart of chess” after he paused for 30 minutes during a match before making his move.

He sacrificed three high-value pieces which enabled him to trap and beat his opponent, Sipke Ernst, in a surprise win.

Source: New Yorker

Carlsen also became a Grandmaster in 2013 after beating former world champion Anatoli Karpov. He was the third youngest player to do so.

Sources: CNN, New Yorker, New Yorker

In 2007, he was winning enough — and earning enough — that his parents formed a company to deal with his prize money.

Source: New York Times

In 2009, he dropped out of school without graduating having decided he wasn’t interested. For about a year during this period, former world champion Gary Kasparov started coaching him.

Coaching didn’t come cheap. It cost Carlsen’s family several hundred thousand dollars, but it paid off. In 2010, after a year of working together, Carlsen reached No. 1 in the world. At 19, he was the youngest person to ever do so.

His working relationship with Kasparov didn’t last though. Carlsen said he was too intense.

“I felt like every day I just had to build up my energy to be able to face him,” he told The New Yorker.

Kasparov also didn’t approve of how casually Carlsen trained.

Carlsen has regularly been labeled “lazy” due to the intensity of his training compared to some of his peers.

Regardless, in 2010, Kasparov told Time, “Before he is done, Carlsen will have changed our ancient game considerably.”

Sources: New York Times, New Yorker, CNN, BBC

It was around this period that Carlsen became a genuine celebrity. He was the first world champion from the West since Bobby Fischer, who became a household name after beating Boris Spassky in 1972.

Andrew Paulson, former chief executive of Agon, a company affiliated with top chess tournaments, told The New York Times that Carlsen was a refreshing change from the typical chess stars who were “old, cranky, strange Russians whose names all start with K.”

Sources: New York Times, BBC, New Yorker, Guardian

Carlsen modeled next to actress Liv Tyler. He was profiled by “60 Minutes.” He got multiple sponsorships from Unibet and a number of Norwegian companies.

One brand manager described Carlsen as a “cross between a boxer and a ’50s gangster.”

Sources: New York Times, BBC

In 2011, Carlsen showed a glimmer of his unpredictability when he refused to compete in the world championships.

He didn’t like how the competition conducted its qualifying matches. He called it a “shallow ceaseless match-after-match concept.”

By skipping the competition, he lost the chance to become the youngest-ever world champion.

Even so, that year he earned about $1.2 million from prize money and sponsorships.

Sources: New Yorker, The Ringer, New York Times

In 2012, he was profiled by “60 Minutes.” In the episode, he played — and beat — 10 different players without ever looking at the chessboards.

“I enjoy it when I see my opponent really suffering when he knows that I’ve outsmarted him,” he said on the show. “If I lose just one game, then usually, you know, I just want to really get revenge.”

Source: CBS News

In 2013, he co-founded the company “Play Magnus,” which started as an app based on his chess history but soon broadened to include online games, training, and publishing.

By 2021, it had 250 employees and around 4 million users, and its shares are worth about $115 million.

He doesn’t work there day-to-day, but he helps with broad strategy.

Source: New York Times

In 2013, he agreed to compete in the world championships. Just before turning 22, he beat then-world champion 44-year-old Viswanathan Anand.

According to BBC, their match was the most widely covered title match since the Cold War.

In their final game, when the competition had already been won, Carlsen could have settled for a draw. Instead, he went for the win.

Kasparov told The New Yorker he wasn’t surprised.

“He likes to play, he likes to win, and he had the better position,” he said. “He’s a maximalist like Fischer, and he expects to fight to the death.”

In the end, Anand got a draw from that game.

Sources: BBC, New Yorker, The Ringer

Carlsen went on to win four more world championships. He beat Anand again, then Sergey Karjakin, Fabiano Caruana, and Ian Nepomniachtchi.

Anand told ESPN Carlsen’s most impressive qualities were his flexibility and unpredictability.

“Whatever situation you drop him, his promptness to react is brilliant,” he said.

By 2018, The New York Times was reporting on the “Magnus Effect.” In Norway, his successes led to a surge in chess popularity.

About 500,000 Norwegians played chess online regularly out of a population of 5 million.

Source: New York Times

But Carlsen himself wasn’t feeling it. He said his goal had only been to win the world championship once. He competed for his third title in 2016 due to other people’s expectations, and he said that his fourth and fifth wins were “nothing.”

Following his victory in the world championship in 2018, he told reporters if he’d lost to Caruana that would have been it. He would have quit the game.

After winning, he said, “Four championships to five, it didn’t mean anything to me. It was nothing. I was satisfied with the job that I’d done. I was happy not to have lost the match, but that was it.”

When the media asked Carlsen and Caruana to pick their favorite players from the past, Carlsen said himself, but from “like three or four years ago.”

Sources: CNN, The Ringer, ESPN, NPR

Even so, in 2019 he went on another winning streak, emerging victorious in eight different tournaments and not losing once in 125 games.

If that wasn’t enough, he also reached the top of football’s official fantasy league.

He said his success in the fantasy league, unlike chess, was down to luck.

Sources: The Ringer, Guardian

When the pandemic hit, Carlsen could no longer tour, but he didn’t stop playing chess. He hosted an online tournament called the “Magnus Carlsen Invitation” with $250,000 in prize money.

During the tournament, Carlsen lost to a 16-year-old player named Alireza Firouzja.

“It pissed me off a lot,” he told CNN.

Even so, online chess’s popularity grew. Between 2020 and 2022, Chess.com doubled its monthly users, ending up at 16 million.

Sources: The Ringer, CNN

In 2021, Carlsen was on another winning streak before he lost to Hans Niemann, a 19-year-old American Grandmaster, during a tournament in the US, who he accused of cheating.

Carlsen immediately left the tournament, which was highly unusual. He later posted on Twitter suggesting he believed Niemann had cheated. Niemann had admitted to cheating before.

Two weeks later, they played against each other again online, but Carlsen left the game after one move. He didn’t immediately explain why he had left, but he later released a statement accusing Niemann of cheating again.

“I believe that Niemann has cheated more — and more recently — than he has publicly admitted,” he said.

In 2022, Chess.com released a report that stated Niemann had likely received illegal support in at least 100 games played online.

Niemann responded by suing Carlsen, Grandmaster Hikaru Nakamura, and Chess.com for $100 million in damages over the allegations.

Sources: The Ringer, NBC News, Vice, CBS Sports

In July 2022, Carlsen also announced he would not be defending his world championship title.

On his podcast “The Magnus Effect” he said, “The conclusion is — it’s very simple — that I’m not motivated to play another match.”

“I simply feel that I don’t have a lot to gain,” he said. According to the Elo rating system, he was already the best ever.

But Carlsen also said he wasn’t walking away forever.

“I don’t see myself stopping as a chess player anytime soon,” he said.

Sources: The Ringer, Five Thirty-Eight

In May 2023, Carlsen made a return to the game without his world championship title at a tournament in Poland.

Carlsen had a seven-game winning streak at the Superbet Rapid & Blitz tournament and held on for a draw in the final game, securing the $40,000 cash prize.

“Already on the third day I was feeling in normal shape, and I thought that’s good, I can actually play chess,” Carlsen said after the tournament. “Whether I’d actually be able to compete for tournament victory at that point I didn’t think about because its too early and not realistic. Even with +10 in the Blitz it was still close but I’m very happy.”

“It’s nice to show that my retirement only lasted a couple of days,” he added.

Source: CNN

Ads by: Memento Maxima Digital Marketing

Ads by: Memento Maxima Digital Marketing

@[email protected]

SPACE RESERVE FOR ADVERTISTMENT

Memento Maxima Digital Marketing

Memento Maxima Digital Marketing