Why Does Islamic State Target Marawi City?

Commentary : The Jakarta Globe |

.

When the Islamic State-linked Abu Sayyaf Group, the Maute Group and their terrorist allies — local and foreign — decided to besiege and occupy Marawi City in Central Mindanao, they should have sensed that they could not hold on forever to the Islamic City.

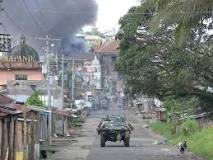

True, they worked fast, deftly and brutally — like good soldiers of the Islamic State (IS). In the early stages of the siege they overran most of the city but now they are holed up in an area the size of half a square kilometer. Clearly they could not — cannot — hold Marawi in any form of a lasting grip, not while the Philippine military remains a respectable force.

The siege has been led by Isnilon Totoni Hapilon, designated amir of the wilayah (province) of the Islamic State in Southeast Asia, a Yakan tribesman from Basilan Island. Although an islander Moro, who headed a faction of the Abu Sayyaf, he was tasked in 2016 to operationally unite the various militant groups in mainland Mindanao that had pledged allegiance to the IS. Thus he would establish an IS headquarters in the area, which would direct terrorist operations all over Southeast Asia.

Supporting Hapilon in this mission is the Maute Group, a band of insurgents led by the Maute family, notably the brothers Omarkayam and Abdullah Maute, who are natives of Butig, a town south of Lake Lanao. The Mautes would have preferred the IS headquarters to rise from their hometown — they had already established a terrorist training camp in the vicinity — but when Hapilon was conducting a plenum there, the military got wind of the gathering and blasted it with air strikes and Howitzer bombardments.

Hapilon was wounded in that attack and had to be evacuated on a makeshift stretcher. Five of his men were killed, along with ten other terrorists. The military then overran the Butig headquarters of the Maute Group.

A sanctuary in Marawi

Such a large cohort of fighters has no feasible escape route from Butig except northward, across the lake and into Marawi City where the Maute family have long-standing links with powerful local personalities. These familiars included former city mayor Omar “Solitario” Ali. Besides, Marawi already had a maze of secret underground tunnels that would come in handy in prolonged urban warfare, which was exactly what happened.

If the Philippine military needed a wake-up call on a strong presence of terrorists in Marawi, it should have been the fatal ambush of intelligence officer Maj. Jerico Mangalus and Cpl. Bryan Libot by Maute fighters within city limits just two weeks after the battle of Butig. In fact, there was no lack of intelligence reports and there was a glut of rumors about IS-linked terrorists about to spring a massive attack on the city, but on May 23 when the military decided to arrest a recuperating Hapilon in Marawi, they sent out a small force, underestimating the opposition. The terrorists simply stormed back and took over several strategic points in the city.

Why did the IS-linked terrorist consortium besiege Marawi? Most probably the IS directly instructed Hapilon, the Mautes and company to grab the city and sculpt it into the Raqqa of Southeast Asia. This would be the follow-up to the designation of Hapilon as amir of the regional wilayah. The soldiers of the caliphate must have been happy to comply: if they succeeded in holding the Islamic City they would have secured eternal fame in the annals of terrorism. If not, they would have had, at least, a chance at martyrdom.

At the same time the militants were seduced by their own bravado. A captured video of Omarkayam Maute giving a tactical briefing to the soldiers of the wilayah in the presence of their amir betrayed a cocksureness that is divorced from reality.

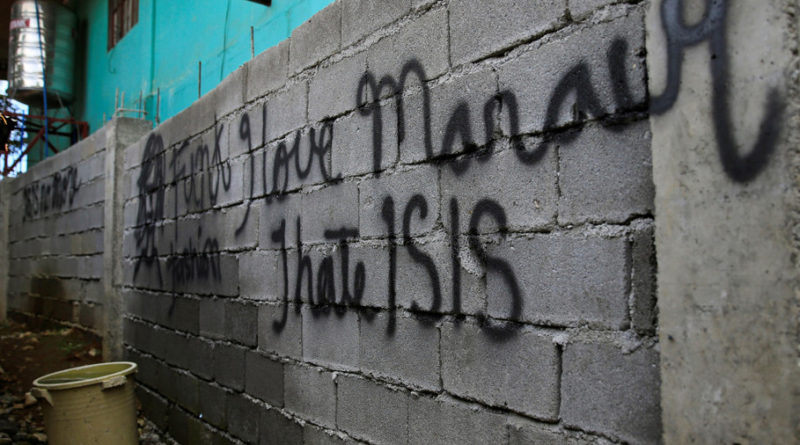

If the jihadists gave no thought to the loss of life and limb and the suffering that their siege would wreak on the people of Marawi, it was not the first time that aggressors completely ignored the wish of the Maranaos of the city to be left alone and to live a normal life.

Marawi’s history of battles

During the Spanish colonial era, in 1891, the governor general in Manila, Valeriano Weyler, organized a force of more than 1,240 Spanish and Indio soldiers to capture the stronghold that dominated the northern shores of Lake Lanao, a fort called “Marahui.” Weyler split the force into two columns: one landing on Iligan to the north, the other on Parang to the south, on the coast of Yllana Bay. The two columns took Marawi in a pincer maneuver.

But the Spanish force held Marawi for only three days. The leader of the Maranao defenders, Datu Aqadir Amai Pakpak, was able to escape and to raise a new and much more formidable force to retake the fort and wreak vengeance on the invaders. The Spaniards deemed discretion the better part of valor and instead of testing the augmented Maranao force, retreated to their coastal bases.

Four years later, a new Spanish governor general, Ramon Blanco, organized a much larger force to retake Marawi but the defenders were well prepared. The battle was fierce and bloody and both sides took many casualties before the Spanish forces prevailed. Among the Maranaos martyred in that fight were Datu Aqadir Amai Pakpak himself and Datu Sinal (Zainal in Arabic), son of the deceased sultan of Marawi.

This time the Spaniards held Marawi a bit longer but after only three years they had to abandon it, as a Filipino revolution in 1896 engulfed Luzon and the Visayas. Then in 1898, the Spanish colonial government too readily and shamelessly surrendered to an American expeditionary force. Marawi would later figure in a very different role as part of the Moro Province under US colonial rule.

Over the ruins of Fort Marawi, the Americans built a military reservation called Camp Keithly, which would decades later be renamed Camp Amai Pakpak, after the Maranao hero. Beside the camp, a cosmopolitan settlement called Dansalan grew. The new entrepot began to attract Christians from the north, Chinese and Japanese artisans and traders and American businessmen. Heavy fighting between the Americans and the Maranaos took place elsewhere around the lake region, in such places as Bayang, Maciu, Bacolod Grande.

In that campaign the Battle of Bayang of May 1902 was the first major clash, which the Americans won only because a young Maranao-speaking American captain named John Pershing befriended and persuaded the powerful datus who ruled the north of the lake not to come to the aid of the embattled Sultan of Bayang. Pershing won the lasting respect of the Maranaos because, while he killed many of them in a subsequent two-year pacification campaign that he led, he spared many more. He released those who surrendered.

So when US President Donald Trump recently claimed that Pershing had ordered his men to shoot Muslim prisoners with bullets dipped in pig’s blood, Trump was telling an idiotic lie that insults the memory of Maranao warriors of that era who engaged Pershing either as an admired friend or as a worthy adversary.

Unfortunately for the Muslims of southern Philippines, Pershing was just one enlightened soldier. He fought brilliant battles and was magnanimous in victory. It is no wonder, then, that he would eventually command a million troops in Europe as a General of the Army during the First World War. But while he was serving in the Moro Province, he did not make policy and US policy about the Moros was not always enlightened. Those discriminatory policies were later perpetuated and worsened by the Manila-centered Filipino government when the Republic was restored in 1946.

Separate National Identity for Muslims

Under American colonial rule (1899-1946) a movement began for a separate national identity for the Muslims of southern Philippines, according to historian Thomas McKenna. For several years, until 1913, the movement was encouraged by the American authorities.

Marawi figured in this movement: in 1935 Hadji Abdulhamid Bongabong and 189 other Maranaos signed the so-called “Dansalan Declaration,” Dansalan being the official name of Marawi at that time. In that document, they entreated that “should the American people grant Philippine independence, the islands of Mindanao and Sulu should not be included in such independence. Our public land should not be given to people other than the Moro nation.” This and similar petitions by other groups of southern Philippine Muslims went unheeded.

Worse, as early as 1901, the American colonial government passed a law on land registration, which launched a policy that led to loss of the Muslim’s ancestral lands to the government or to Christian settlers from the north. What the Americans began the Philippine Commonwealth Government that was established in 1935, and the Philippine Republic that was restored in 1946 compounded and magnified. The result was that the Muslims were almost entirely deprived of the lands they inherited from their ancestors.

A lasting grievance

In 1983 I had the privilege of interviewing one of the dispossessed, Dr. Mamitua Saber, grandson of one of the heroes of the 1891 and 1895 Battles of Marawi, the Maranao cannoneer Datu Sinal. As a son of the late Sultan of Marawi, Datu Sinal was sure of his claim to the site of Fort Marawi as ancestral land, and accordingly his family built a home on a portion of it. The Philippine government, however, officially judged them “squatters.”

This is a grievance shared by thousands of Muslims all over Mindanao: the issue of the restoration of ancestral lands. It is supposed to have been addressed by several peace agreements between the Philippine government and the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and its main spin-off, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). One of these is the GRP-MNLF “Final” Peace Agreement mediated by Indonesia in the 1990s. But still the grievance is yet to be redressed.

Aside from the issue of ancestral lands, there is the issue of poverty and underdevelopment in the provinces with majority Muslim populations, which fuels the rhetoric of separatist-terrorist propaganda. Marawi is often billed as a metropolis; in fact it is the capital of, by official reckoning, the poorest province in the Philippines. There is also the element of inter-communal hatred born of religious prejudice.

It was only natural therefore that the opening battle of the Moro separatist rebellion should break out in Marawi, which happened on 21 October 1972, exactly a month after President Marcos declared martial law. Call this the third siege of Marawi.

It was largely a local uprising of several hundred fighters, few of whom, if any, belonged to the MNLF. It was triggered by rumors that martial law was declared to disarm and to forcibly convert the Muslims to Christianity. The attack was quickly suppressed but it forced the MNLF to push its war schedule forward.

From 1973 to 1974 the MNLF was generally successful in battle, but in the years that followed, Marcos outwitted the rebels in the international arena. Fortuitously for Marcos, in 1974 the then foreign minister of Indonesia, Adam Malik, persuaded the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) to frog-march MNLF Chairman Nur Misuari to the negotiating table. After the signing of a framework peace agreement between the government and the MNLF, the Tripoli Agreement of 1976, the Front began to splinter with the breakaway in 1978 of a faction that would become the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF).

Over the years the original separatist rebellion, which had exacted a toll in human lives that numbered more than a hundred thousand, morphed into a peaceful political process. Thus the MNLF and the MILF today are working with the government to ensure peace and development to the Muslim-dominated provinces of southern Philippines, which will form an autonomous region called “Bangsamoro.”

The current crop of insurgents — the Abu Sayyaf, the Maute Group, the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters, and others that have sworn allegiance to the Islamic State — would have none of this: they don’t want autonomy, not even a federal state of their own. They want not only to break away from the republic but also to incorporate themselves into a global caliphate whose best promise is either martyrdom now or the early coming about of the apocalypse.

After the siege, what?

Meanwhile the Fourth Siege of Marawi is winding down. As I write, a contingent of the Philippines’ First Marine Brigade has just crossed the Mapandi Bridge leading to Marawi’s commercial district of Banggolo where the remnants of the terrorist force that harrowed the city are expected to make their last stand. They may yet spring a few surprises, but their tactical limitations, including the constriction of their logistics and their inability to take in reinforcements, have to catch up with them some time.

But after the last jihadist in Marawi has been dispatched to paradise, that should not be the end of it. That is when the government must focus on the more strategic battle — for hearts and minds.

First, Marawi must be rebuilt and this must be done right — with exhaustive planning and efficient execution. The rebuilding of Marawi has a national context. It should be part and parcel of the larger effort to bring peace and development in Mindanao — to rescue the stymied peace process.

It is heartening that the Mindanao Development Authority (Minda) under Datu Hj. Abul Khayr Alonto and the League of Cities of the Philippines (LCP) have formalized their support for this effort through a memorandum of cooperation.

But more than that is needed. It may be time to harness an executive order that President Duterte issued last year that enabled the Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process (OPAPP) “to oversee all development projects and at the same time empower it to implement projects that are related to peace. The implementation of massive development on the ground will be done simultaneously with the work to implement agreements that government had [sic] entered into.”

In this regard, the Philippines can take a page from the way Indonesia rebuilt Aceh after the massive tsunami devastation of December 2004. In April 2005 the government established the Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Agency (BRR) for Aceh and Nias and gave it huge powers. It consisted of an executing agency and two independent oversight agencies, all of them reporting directly to President Yudhoyono.

A veteran public servant with a reputation for getting things done, Kuntoro Mangkusubroto, was appointed director of the BRR executing agency and he at once coordinated reconstruction efforts, matching donated funds with the felt needs of the affected communities.

The BRR operated in a non-nonsense way that was responsive to the situation on the ground. It also put great emphasis on capacity building so that the affected communities would not have to depend on the BRR forever. In a few years Aceh fully recovered from the demolition by the tsunami that killed 230,000 Indonesians. It also ceased to be the hotbed of a separatist rebellion.

Bangsamoro Autonomous Region

The OPAPP could serve as the Philippine version of the BRR, except that OPAPP has a broader mandate: wherever there is a peace process, whether it be with the Bangsamoro, the communist insurgents, or the highlanders of Northern Luzon, it is called upon to facilitate a peaceful resolution. But it also has a robust development mandate: it can, for example, speed up the implementation of the Development Master Plan for the Ranao-Agus River Basin, which covers the Lake Lanao area, where Marawi can once again function as the hub of economic activities.

It can give a big push to the execution of the Liguasan Marsh Master Development Plan, a long-existing plan designed to improve the lives of the Maguindanaons. For the Tausugs, Yakans, Samals and Badjaos of the Basilan, Sulu and Tawi-Tawi archipelago, it can inject more life to the BIMP-EAGA effort, which has been moribund in spite of the launching of the Davao-Gen. Santos-Bitung Roll On, Roll Off operations earlier this year. And energize the plan to establish an ecozone, possibly a transshipment hub, in the Sibutu Passage between Tawi-Tawi and Borneo.

Above all of these, the one factor that can actually bring about durable peace in Marawi and everywhere else in southern Philippines is the successful passage — hopefully within this year — of a Basic Law for the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region (BL-BAR) that is free of the deficiencies and defects of earlier versions.

This watershed legislation will create a region consisting of the provinces with majority Muslim populations, which will enjoy meaningful autonomous powers. It will embody in a single document the spirit of the the Tripoli Agreement of 1976 and the Final Peace Agreement of 1996 between the Philippine government and the MNLF, which was mediated by Indonesia, as well as the Comprehensive Agreement on Bangsamoro between the Philippine government and the MILF, which was mediated by Malaysia.

And thus it will be the culmination of the struggle of the Muslims of southern Philippines for self-determination, the end of their marginalization, the redress of their grievances and a fair chance for a better life through economic and social development.

The proposed basic law is the handiwork of a Bangsamoro Transition Commission (BTC) in which no significant group or community — Muslim, Christian or Lumad — has been left out. Even the Misuari faction of the MNLF, which refused to work with the Commission, will have its own inputs taken into account when Congress deliberates on the legislation.

But should the Basic Law that comes out of Congress be less than what is envisioned by the BTC, or should its implementation fall short of rectifying the political, economic and social inequities that the people of the autonomous region — Muslim, Christian and Lumad — have suffered over the decades, the siren call of extremist insurgency will continue to seduce a part of the population. That was how discontent at earlier peace processes led to the founding and growth of such terrorist insurgent groups as the Abu Sayyaf, the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF) and the Maute Group.

And that is why the Basic Law for the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region perforce has to succeed. The Philippines cannot afford to suffer any more tragic sieges like the ongoing one in Marawi.

<>

NOTE : All photographs, news, editorials, opinions, information, data, others have been taken from the Internet ..aseanews.net |

[email protected] |

For comments, Email to : [email protected] – Contributor