EDITORIAL Just ruling—but far from over

EDITORIAL

EDITORIAL

Just ruling—but far from over

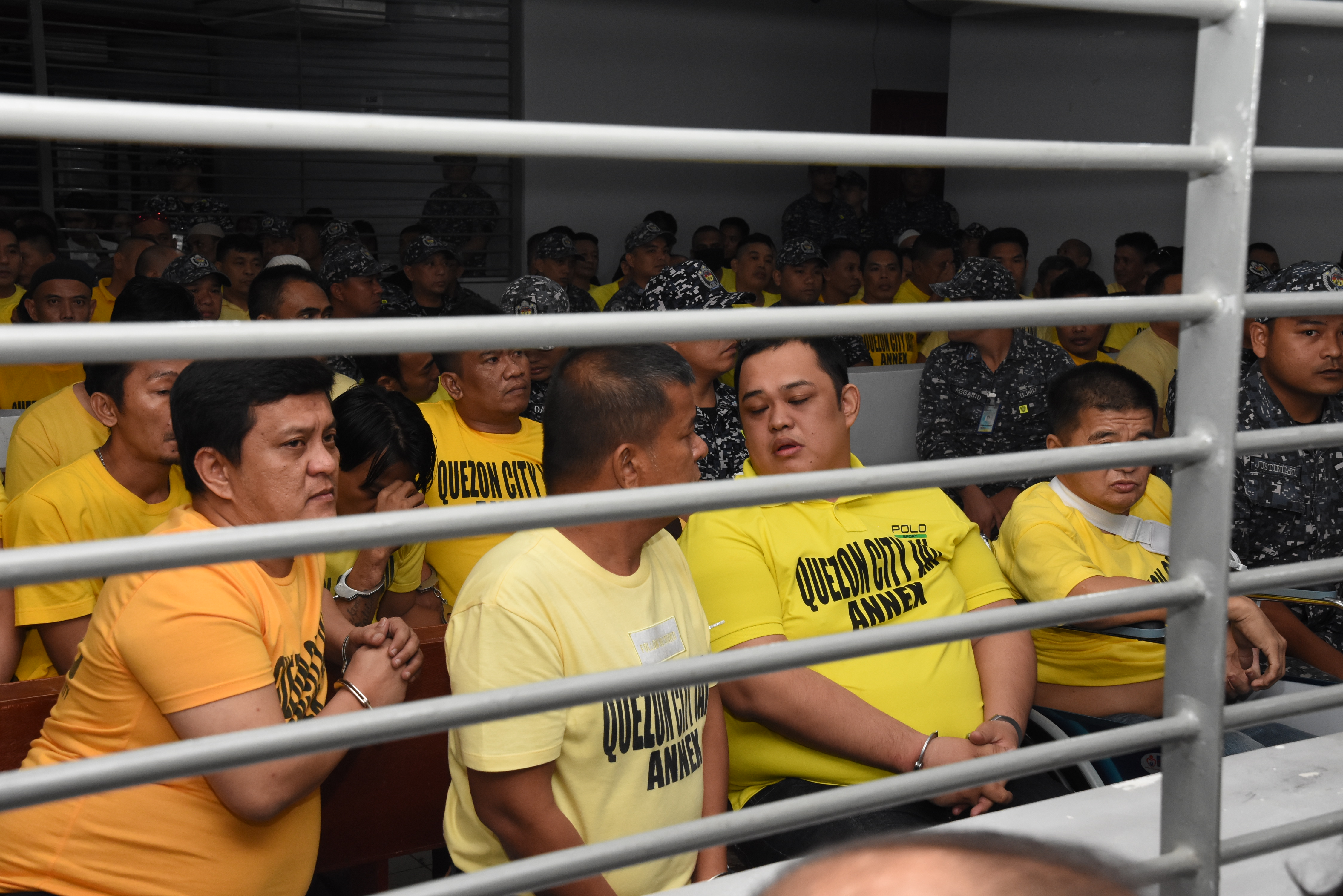

JUSTICE SERVED Quezon City Judge Jocelyn Solis-Reyes concludes the Maguindanao massacre case on Thursday with a guilty ruling against brothers Andal (left) and Zaldy Ampatuan (right, partly hidden) and other members of the influential political dynasty. PHOTO COURTESY OF SUPREME COURT PIO

We will be their witness,” we wrote in a front-page editorial on Nov. 29, 2009, six days after 58 lives were snuffed out by the Ampatuans’ private army on a lonely hilltop in Maguindanao. And through the years up to yesterday when Judge Jocelyn Solis-Reyes handed down her verdict, the Inquirer, along with other media, has faithfully reported on the terrible crime that thrust the Philippines squarely on the map for the single deadliest attack on journalists in the world. In bearing witness, we strived mightily to “piece together the bloody shards of the crime,” and to find the words to “approximate the horror.”

It took almost 10 years for Judge Solis-Reyes to hear the case at Camp Bagong Diwa in Taguig City and to pronounce Andal Ampatuan Jr. et al. guilty of mass murder. But could she have possibly handed down another verdict? On what some lawyers have described as an “open-and-shut case”? Whether in the wise estimation of Lady Justice or under the indifferent gaze of the Universe, after all these years of waiting by bereaved wives and husbands and children and siblings and assorted other kin dealt with a loss so grave only a just ruling could help ease the pain? “We will keep asking the terrible question: How could this have happened?” we wrote.

The observer attentive to issues of underdevelopment in this unhappy archipelago may note that the setting of the mass murder appeared preordained. Maguindanao, primarily agricultural and wracked by a fierce struggle for power among those who held sway over it, was the quintessential badlands, a seemingly ideal place for the massacre that occurred in the town that bears the Ampatuans’ name. But for certain families comprising its elite, Maguindanao’s people were impoverished: It was, per a 2003 survey, the second poorest province in the country, with more than 60 percent of the population living below the poverty line. But that fact is said to have hardly prevented members of the ruling clan from keeping Makati’s luxury-shop owners happy with their profit margins.

For wealth and power to stay in the same hands, therefore, it was necessary that the state of affairs be maintained, that no upstart be permitted to disturb the balance. From that perspective, the convoy that was heading to the Commission on Elections office in Shariff Aguak to file the papers for Esmael Mangudadatu’s candidacy for governor of Maguindanao—the then vice mayor’s bold challenge to the Ampatuans—was doomed. The body count is unforgettable: 58 men and women mowed down by gunmen wielding high-powered firearms, including 32 journalists and media workers, as well as the unfortunate occupants of a vehicle that was merely passing through. How to understand how the clan led by former Maguindanao governor Andal Ampatuan Sr. (since dead, having expired while in detention) could conceive of so barbaric a crime (the plan was sealed over dinner, according to a witness’ account), and proceed to methodically, fearlessly, implement it? It is important to examine their connections, the powerful figures in whose reflected light they had basked and whose back they had dutifully scratched. That they had been a close ally of then President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo since 2001 was doubtless a primary factor in their reckoning. How valuable the clan was to Malacañang was demonstrated by the official results of the 2004 presidential election: Arroyo won a thumping victory in Maguindanao, with her opponent, the actor Fernando Poe Jr., notching an unbelievable zero in at least three towns. The weight of the Ampatuans’ connections was affirmed in a paper written in June 2007 by the Action for Economic Reforms. The group said that the Ampatuans’ monopoly of political power in Maguindanao had the blessings of the central government, and that the clan was dependent on the Palace’s patronage.

The promulgation of the judgment on the Maguindanao massacre case done, and despite the pronouncement of President Duterte’s spokesperson Salvador Panelo that “the rule of law has prevailed,” the matter is far from over: Of the 197 charged with multiple murder, as many as 80, including members of the Ampatuan clan, remain at large. The issue of the 58th victim, Reynaldo Momay, is unresolved. And the long list of those acquitted is unacceptable to certain grieving families.There are significant lessons to be learned—and acted upon. Despite the hope stirred by Judge Solis-Reyes’ guilty verdict, the length of time it took to try the case—including the endless delay caused by the defense’s motions for her to recuse herself and the withdrawal and replacement of defense counsels, to speak nothing of the bail hearings for Ampatuan Jr.—reflects the dismaying state of the judicial system.

And journalists and media workers remain in peril in the fast-shrinking democratic space.