PDI: ‘Tokhang’ and its new tack

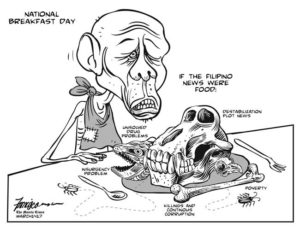

The veil of fear, it appears, has been pierced, the silence broken. Survivors and families of victims of “Operation Tokhang” are coming out and speaking up, and a few have even made the courageous step of taking the Duterte administration to court for human rights violations. The likes of Efren Morillo, a 29-year-old fruit vendor and survivor of a drug raid last year in Payatas, Quezon City, still has a long way to go to see his case through. But his complaint for murder, frustrated murder, robbery and planting of drugs and firearms against the police, following an earlier court ruling that granted him and four other families of Tokhang victims a protection order keeping the cops away from them under the writ of amparo, is sufficiently significant as the first counter-salvo by citizens who have had enough of the brutal government campaign.

Actions like these, as well as shocking incidents like the abduction and killing of Korean businessman Jee Ick-joo right inside Camp Crame, and damning revelations such as the recent Human Rights Watch study which concluded that the police mostly killed suspects and also “routinely planted guns, spent ammunition, and drug packets next to the victims’ bodies,” have hacked away at the legality and moral legitimacy of President Duterte’s keynote governance program.

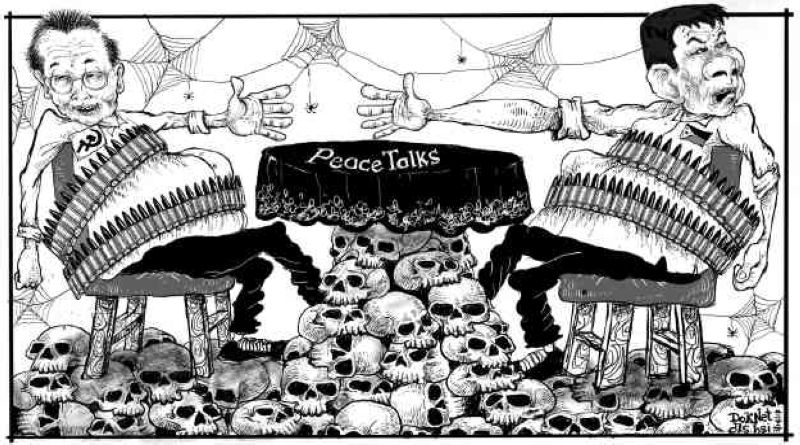

Ominously, the HRW report carries a warning about where this might all end up: “Even if not directly involved in any specific operations to summarily execute any specific individual, President Duterte appears to have instigated unlawful acts by the police, incited citizens to commit serious violence, and made himself criminally liable under international law for the unlawful killings as a matter of command responsibility.”

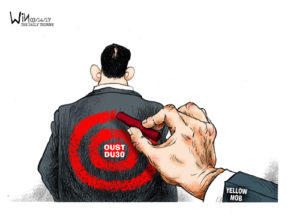

Yet, despite the questionable incidents that have essentially taken the wind out of Tokhang’s sails and rendered it a much-compromised campaign, the government has relaunched it after a month or so of official suspension. The promised cleansing of the police ranks triggered by the Korean businessman’s murder has amounted to nothing more than shipping a handful of supposedly crooked cops to Basilan. But even that was marked by chicanery, with some policemen complaining that the true scalawags in their ranks had paid superiors to evade the reassignment.

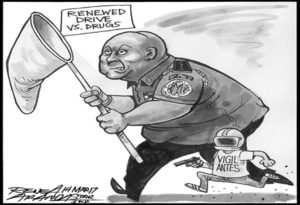

Philippine National Police Director General Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa, as the chief face of Tokhang, has spent much PR spin at putting a benign sheen to it. But, as the proverb says, “You can put lipstick on a pig, but it’s still a pig.” The spectacle of the PNP chief playing Santa Claus to the orphaned children of drug raid victims, as if his clowning around could make up for the devastating loss at the core of their families, only left a galling taste in the mouth.

This time, with the resumption of the war on drugs, Dela Rosa has taken a new tack: inviting priests to join the house-to-house visits by police on suspected drug users and pushers—“para makita talaga nila na ito ay ginagawa dahil sa concern natin sa mga kababayan nating nalulong sa droga at hindi ito maaabuso” (so they can see that we’re doing this out of concern for our countrymen addicted to drugs, and that no abuse happens).

Like the country’s top cop playing Santa to the kids of people his men have killed, the invitation for priestly participation in drug operations is just as absurd and laughable. As Inquirer columnist Randy David correctly noted, “The Church can minister to the needy and the oppressed, even as it pursues its fundamental role of educating consciences. But law enforcement is not its function.”

A government program clearly running out of useful ideas yet still resulting in the killing of more Filipinos ought to be suspended for good.