OPINION: Fall of Kabul: The Tragedy of a Post-American World

OPINION

America couldn’t overcome the inertia of history.

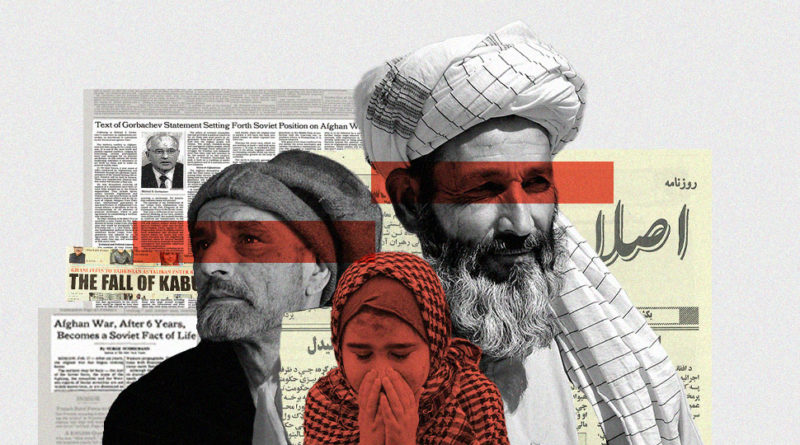

“Does ‘republic’ mean Father and I will have to move away?” asked Hassan, the green-eyed, harelip servant boy with a “China doll face,” in one of the most haunting lines in Khaled Husseini’s wrenching novel, The Kite Runner. Here was an achingly innocent child, who simply wondered if ethnic Hazaras like him, professing the minority Shia faith and standing apart for his East Asian features, had a place in the new political order in Afghanistan.

They say truth is the first casualty in war, but in Afghanistan, innocent people, especially vulnerable minorities, often bear the brunt of violent political upheavals. The past half-century has stood witness to the most profound suffering of countless children and women, liberal intellectuals, and ethnic minority members like Hassan’s fellow Hazaras.

Ruins of Kabul’s Dar-ul-Aman Castle

Following the collapse of Afghanistan’s centuries-old monarchy in the early-1970s, various authoritarian regimes of all stripes violently jostled for power, thus plunging the whole country into internecine conflict and generalized immiseration.

The dramatic yet broadly bloodless fall of Kabul, the country’s capital, over the weekend sent shockwaves across the world.

Afghanistan’s recent history is riddled with pogroms and purges. Hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians have perished, while millions of others have been turned into permanent refugees in neighboring Pakistan, Iran, and beyond. Western observers often describe Afghanistan as a “graveyard of empires,” yet the greatest tragedy is the human toll of these endless conflicts.

The dramatic yet broadly bloodless fall of Kabul, the country’s capital, over the weekend sent shockwaves across the world. No one, including the Taliban, foresaw the stunning collapse of the entire Afghan government, as authorities in Kabul lost control over major cities of Herat, Kandahar, and Mazar-i-Sharif in a matter of days.

Kabul City View

The triumphant return of the Taliban, a fundamentalist Sunni group that is dominated by ethnic Pashtuns, made me think of real-life Hassans, who must be deeply anxious about their future, if not survival, under their new rulers. I couldn’t help but worry about all the independent journalists, parliamentarians, and civil society leaders, especially women and those from ethnic minority backgrounds, who inspiringly thrived under the fragile democratic order of recent years, but are now suddenly wondering whether they are on a Taliban hit list.

.

No one, including the Taliban, foresaw the stunning collapse of the entire Afghan government.

Perhaps, the biggest question at this point is whether all of this is inevitable, and what are the long-term implications of the fall of Kabul. Was Afghanistan a “lost cause”? And what does the Biden administration’s “exit without strategy” debacle say about the future of an increasingly post-American global order? The answer to these fundamental questions can be gleaned from a deeper understanding of history.

The Original Sin

On July 17, 1973, Sardar Mohammed Daoud Khan, an aristocrat and erstwhile statesman toppled his first cousin Mohammed Zahir Shah, Afghanistan’s last king, in a bloodless coup. Eager to accelerate the pace of reforms, Daoud Khan established a republic and, along with his socialist allies, pressed ahead with massive educational and social reforms, which turned Afghanistan into one of the most cosmopolitan societies in the Muslim world. From Kabul to Tehran, Baghdad to Istanbul, women enjoyed unprecedented rights as academics, civil society leaders, and even fashion icons.

Mohammed Zahir Shah, the Last King of Afghanistan

Nevertheless, Afghanistan’s first president was a consummate autocrat, who steadily alienated then violently purged a growing section of his supporters and rivals. Crucially, Khan’s decision to abolish the country’s most enduring national institution, the monarchy, set in motion a dangerous trend, which continues to haunt Afghanistan to this date.

The tyrannical lurch ended in his assassination in 1978, as communist forces launched their own Saur Revolution. Yet more trouble was to come. Torn between the more moderate Parcham (“flag” in Persian) and the radical Khalgh (“masses” in Persian) factions, the ruling Communist People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) went on a self-destructive mode.

Eager to aid its embattled communist proxies, the Soviet Union stepped in and deployed large-scale military forces under the so-called Brezhnev Doctrine. Soon, Afghanistan transformed into a theater of international conflict among competing global and regional powers.

For almost a decade, Soviet-backed communists, led by Babrak Karmal and his fellow Parchamists, desperately sought to create a socialist society while waging a bloody conflict against U.S.-backed Mujahideen (Islamic guerilla fighters) as well as a cacophony of Maoist and smaller rebel groups. The end of the Cold War, however, didn’t bring respite to Afghanistan. If anything, the exact opposite happened.

An Afghan boy playing with his kite in Herat, Afghanistan. (October 24, 2012).

Just a year after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, their communist clients in Kabul followed suit. The ensuing power vacuum triggered a full-blown civil war among various warlords and former Mujahedeen fighters from across ethnic lines. After years of devastating conflict, the surprising winners were no less than the Taliban, a rugged band of humble-folk fundamentalists.

Led by the charismatic Mujahidin fighter Mullah Mohammed Omar, the Taliban (“seekers” in Pashto) triumphed based on the strength of their religious devotion and an uncanny populist sincerity, which appealed to large sections of the Afghan society. But as Rahim Khan, the beloved uncle in The Kite Runner, put it: “Peace at last. But at what price?”

Recognized by only three countries, their Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan was notorious for its medieval-style justice system and systematic brutality against minorities. It only lasted for five years. Americans invaded the country following the 9/11 attacks organized by al-Qaeda, an extremist group that happened to be generously hosted by a fellow traveler Taliban throughout the late-1990s. Yet, that was far from the end for the stern and reclusive rulers of Afghanistan.

A Graveyard of Hubris and Hopes

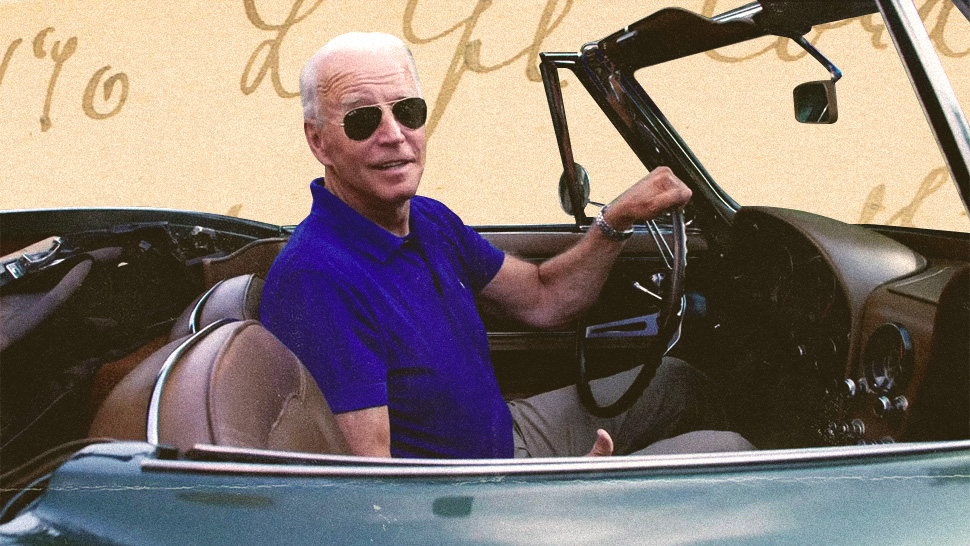

“The likelihood there’s going to be the Taliban overrunning everything and owning the whole country is highly unlikely,” claimed U.S. President Joseph Biden just weeks before he was proven spectacularly wrong. As if that wasn’t enough reassurance, the American leader also went on to claim, “There’s going to be no circumstance where you see people being lifted off the roof of an embassy of the United States in Afghanistan.”

Up until late June, the U.S. intelligence agencies confidently predicted that the Afghan Government will likely survive for at least six months following the withdrawal of Western forces. But even this prediction seemed a tad too grim since Moscow-backed communists in Kabul lasted for almost three years following the full withdrawal of Soviet troops by 1989.

The Taliban’s lightning-speed victory shouldn’t come as a big surprise.

In retrospect, however, the Taliban’s lightning-speed victory shouldn’t come as a big surprise. To begin with, Afghanistan remains an unfinished nation-building project, ever divided along ethnic-religious lines in extremely difficult topography.

There is a reason why one Afghan president after the other has been derisively described as “mayor of Kabul,” given the perennially tenuous control of the national government over much of the countryside.

For centuries, large parts of Afghanistan—extending as far as the northern province of Balk, the birthplace of the great poet of love, Rumi—were under various Persian imperial dynasties. More specifically, it constituted a core element of the so-called “Greater Khorasan” region, which extends from the eastern provinces of modern-day Iran all the way to northern Afghanistan and parts of Tajikistan and Turkmenistan.

In fact, the very suffix “istan” comes from a Persian word, which can be roughly translated as “land” or, in modern Farsi, “province.” It was not until the demise of 18th-century Persian King, Nader Shah, who conquered large parts of northern India, that modern Afghanistan began to develop as a distinctly separate nation-state under the emerging Durrani Empire.

The decline of 19th-century Persia, which failed to retrieve parts of Afghanistan it claimed as its own, triggered a so-called “The Great Game” between the ascendant British and Russian empires across Central Asia and the Middle East. As a result, Afghanistan’s modern identity, as well as nation-building project, was largely shaped by its resistance to imperial incursions by the Western powers to the north (Russia) and south (British India).

Despite repeated military incursions and bombardments of Kabul, the Brits were at best successful in paying off a few Afghan emirs against defecting to Czarist Russia, a fragile arrangement that the Third Anglo-Afghan War ended in style.

After 20 years of occupation, spending $2 trillion to build a modern Afghan state and train 300,000 national troops, America couldn’t overcome the inertia of history.

Nevertheless, land-locked and mountainous Afghanistan struggled to truly establish a modern nation-state as in neighboring Iran or Turkey, which developed highly centralized political institutions based on a well-defined nationalist project. Post-Ottoman Turkey adopted a curious combination of republicanism and pan-Turkism, while Iran embraced the glories of ancient Persia and the spiritual intensity of Shia Islam.

U.S. Marines take cover while being engaged in small arms combat in Kajaki, Afghanistan (March 19, 2012)

There was no parallel movement in Afghanistan, which remained economically isolated, politically fractious, and socially conservative despite a string of reformist leaders, including its last King, Mohammad Zahir Shah. Clearly, half a century of conflict and instability following the establishment of the republic in 1972 further undermined visionary efforts to accelerate the country’s political modernization.

After 20 years of occupation, spending $2 trillion to build a modern Afghan state and train 300,000 national troops, America couldn’t overcome the inertia of history or the revolt of geography. If anything, it may have further contributed to the problem.

On one hand, Washington largely relied on former warlords and traditional politicians to run the post-Taliban government in Kabul. In her classic work The Punishment of Virtue, Sarah Chayes meticulously chronicles the emergence of a deeply corrupt and inefficient Afghan Government under American patronage, sowing the seeds of its overnight collapse in the future.

U.S. Marines gather around to listen to acting Marine Corps Commandant General James F. Amos in Kajaki, Afghanistan. (February 5, 2012)

As a result, countless soldiers and civil servants went underpaid or unpaid altogether, while barely two million Afghans, in a country of almost 40 million people, bothered to cast their vote in the last democratic elections in 2019. As soon as Americans began to withdraw, a growing number of Afghan politicians began cutting deals with the Taliban, while soldiers didn’t see the point of sacrificing themselves for a corrupt and illegitimate government.

The Taliban thrived as a major guerilla and political force by consciously presenting itself as a genuine resistance movement against Western occupiers.

Meanwhile, America’s very presence provided ideological fodder to Taliban forces. Throughout the past two decades, the Taliban thrived as a major guerilla and political force by consciously presenting itself as a genuine resistance movement against Western occupiers and their puppet regime in Kabul. Even more crucial was their uncompromising piety and religious zeal, which inspired Taliban fighters to endure far more suffering and embrace far greater risk than the increasingly demoralized Afghan national forces.

As Carter Malkasian, who speaks Pashto and met countless Taliban leaders in the course of writing his new book The American War in Afghanistan, argues, “More Afghans were willing to serve on behalf of the government than the Taliban. But more Afghans were willing to kill and be killed for the Taliban. That edge made a difference on the battlefield.”

A young Afghan boy plays with the photographer in this shot taken in Helmand, Afghanistan. (August 2011)

Twilight of an Empire

In the end, there wasn’t much of a battlefield at all, as regional governors seamlessly surrendered like a domino to Taliban fighters in the wake of American withdrawal. A bit of sound negotiation and old-style bribery sealed the deal. As for the Afghan national army, it simply melted away. Many Taliban fighters simply used their rifles in celebration, jubilantly firing into the air as they triumphantly cruised through the gates of conquered cities.

In Kabul, Taliban fighters quickly took over the presidential palace, posing before international media in a seat that used to be occupied by former President Ashraf Ghani, a once-celebrated global thinker who chose to escape than to defend his people in the darkest hour.

Even more shocking was the stunned look of top American officials, who effectively begged Taliban forces to not attack their diplomatic representatives and allow for their swift evacuation. In desperation, the U.S. had to move its embassy to the city’s international airport, frantically processing thousands of visa applications.

Afghan refugee girls smile in a camp in Lahore, Pakistan. (December 8, 2014)

The big-picture geopolitics was always clear. Biden, who consistently opposed the “mission creep” in Afghanistan throughout the past decade, has been determined to disentangle from the Middle East in order to refocus America’s strategic resources on China. For him, the 21st century is an existential battle between American democracy and Chinese authoritarianism for global mastery.

This explains why Biden adamantly opposed suggestions by top generals to further delay the withdrawal and, if possible, maintain a “residual” yet decisive force, which could provide tactical and moral support to Afghan national forces. The argument is that great numbers of Afghan soldiers were willing to fight along with Americans, as they have done throughout the past decade, but not for the corrupt and inept leaders in Kabul.

This middle path, whereby there is neither full withdrawal nor provocative surge, could have forestalled a total Taliban victory; if anything, it could have even, at least in theory, frozen the status quo indefinitely in favor of a truly inclusive post-American national government. Without American support, the government in Kabul had no leverage over Afghan forces.

In fact, former President Donald Trump didn’t even bother to invite the Ghani administration to American negotiations with the Taliban in Doha, Qatar. To make it worse, he even considered inviting Taliban forces to Camp David for an intimate retreat. In the words of former U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan Ryan Crocker, the withdrawal blunder “began under President Trump when he authorized negotiations between the U.S. and the Taliban without the Afghan government in the room,” which was a huge “demoralizing factor for the Afghan government and its security forces.”

Biden’s hasty withdrawal, which was largely conditioned by former President Donald Trump’s brittle deal with Taliban forces last year, saw good strategic intentions undermined by grievous tactical errors. The unfolding debacle in Afghanistan, which will likely be seen as one of the greatest intelligence failures in modern history, has instead raised major questions over America’s reliability as well as its commitment to allies elsewhere, including those in Asia. In geopolitics, optics matter. And America’s rivals, from Russia to China, are juicing it out.

In Moscow, countless newspapers, drenched in Schadenfreude, have been mocking the overnight collapse of U.S.-backed government like a house of cards. In Beijing, the jingoistic state-backed newspaper The Global Times quickly unleashed a fiery editorial, where it declared “from what happened in Afghanistan, those in Taiwan should perceive that once a war breaks out in the Straits, the island’s defense will collapse in hours and U.S. military won’t come to help. As a result, the DPP will quickly surrender.”

Defeats in Afghanistan have often been followed by an imperial twilight.

In the Philippines, a major U.S. treaty ally with a Beijing-friendly president, critics from both right and left have been lambasting the “unreliable” America. Though popular among Filipinos, the United States has suffered from a credibility gap in the Southeast Asian country. According to a 2017 survey, almost half of Filipinos were either disagreed (17 percent) or were undecided (33 percent) when asked whether the Philippines’ alliance with America has been “beneficial to the Philippines”.

Mind you, almost half of Filipinos (47 percent) stood behind President Rodrigo Duterte’s pivot to China and Russia at the expense of the Americans. Lingering doubts over American credibility may explain why under Duterte majority of Filipinos (67 percent) supported warmer ties rather than confrontation with Beijing, according to a Pew Research Center survey. In short, Filipinos may love America, but they also doubt whether it would come to their rescue when push comes to shove.

Kabul is likely a preview of what a post-American order would look like: a messy, unpredictable, and anarchic world where no single nation is truly in charge.

Across Southeast Asia and beyond, countless fence-sitters and Beijing proxies will cite the Afghan debacle ad infinitum in order to pursue warmer ties with China. Paradoxically, Biden’s sincere efforts to disentangle from the Middle East may have unwittingly strengthened the hands of America’s critics in Asia. The problem was not one of intention, but instead execution. Amateurs love to discuss strategy, but professionals make sure we get logistics right.

Defeats in Afghanistan have often been followed by an imperial twilight, most dramatically in the case of the Soviet Union, which collapsed only years after abandoning its Afghan allies. Thanks to its dynamic economy, rich natural resources, and growing population, the United States will likely remain a major power for decades to come.

Yet, the dramatic fall of Kabul is likely a preview of what a post-American order would look like: a messy, unpredictable, and anarchic world where no single nation is truly in charge and, accordingly, multiple powers are brutally jostling for evanescent control over helpless nations across strategic regions. But who knows, maybe, it will turn out differently and for the better. As the Zen master, in a tale narrated by the marooned intelligence officer Gust Avrakotos in Charlie Wilson’s War, wisely cautioned: “We’ll see.”

.

Richard Javad Heydarian is a professorial chairholder in Geopolitics at the Polytechnic University of the Philippines and a regular contributor to the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), Brooking Institution, and Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). He has delivered lectures at Harvard, Stanford, and Columbia Universities, was a visiting fellow at the National Chengchi University (Taiwan), and is an assistant professor in Political Science at De La Salle University. He has written for The New York Times, Washington Post, The Guardian, and Foreign Affairs, and is a regular contributor to Aljazeera English, Nikkei Asian Review, South China Morning Post, and the Straits Times.