The facts against China

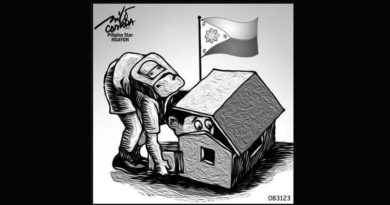

Senior Associate Justice Antonio Carpio of the Supreme Court says he has a “civic duty” to sound the alarm: The Philippines may lose the West Philippine Sea, including 80 percent of its exclusive economic zone and 100 percent of its extended continental shelf, if it does nothing to stop China’s creeping expansionism in the region. He told the Meet Inquirer Multimedia forum on Monday: It is “the civic duty of every Filipino to defend our territory, defend our maritime entitlements in accordance with international law and our Constitution.”

To meet this civic duty, he suggested a three-anchor policy, borrowed from the Vietnamese experience: be friendly with China, defend Philippine territory, cultivate alliances. All three anchors must be in place, otherwise the ship of state will continue to be at risk.

Public opinion largely supports the legal approach that the Philippines took in its dispute with China, the same approach which led to the sweeping arbitral tribunal victory of July 12, 2016. That same public remains largely mistrustful of China.

There is a vocal segment of the public, however, which is ready to accept friendlier relations with China, including billion-dollar loans, but consider defense of territory inconvenient and stronger alliances unpatriotic or insufficiently post-ideological.

As a group, they subscribe to several untruths; we should set them right with the following facts:

The main cause of the South China Sea disputes is China’s aggressive expansionism in the region. The conflicting claims, involving not only the Philippines and China, but also Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia and Taiwan, are not reducible to a geopolitical power play between China and the United States. The claims are rooted in Beijing’s irresponsible and unsupported assertion—first made only in 1947, refined in 1950, and officially announced to the United Nations only in 2009—that China enjoys “indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters, and enjoys sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the relevant waters as well as the seabed and subsoil thereof.” This sweeping assertion violates both the letter and spirit of the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, to which all disputants are signatories.

The notion that the Philippines is a mere plaything trapped in a contest of wills between two superpowers reassures those who wish to take no resolute action against China, but it is not based on reality. The United States is necessarily a factor in the disputes, in part because the biggest economy with the largest navy has a vested interest in freedom of navigation through the vital South China Sea, and in part because it has a Mutual Defense Treaty with the Philippines. But to assert that the United States bears equal blame for the current disputes is to engage in the worst sort of false equivalence. Since the 1980s, China has been expanding its hold on the Paracels, on the Spratly, and now even on Scarborough Shoal.

The case that the Philippines filed with the arbitral tribunal is not the cause of the current tension—and it is appalling that some Filipinos actually think this is true. The Philippines was forced to file the case after the Chinese deception in 2012, when they took control of Scarborough Shoal. That year, a standoff between Philippine and Chinese fishing vessels at the shoal led to a diplomatic initiative; the United States brokered a deal agreed to by the foreign ministries of both the Philippines and China that called for a mutual withdrawal from the shoal. The Philippines complied; China did not.

The arbitral tribunal ruling is a true landmark—a sweeping victory for the Philippines (because it invalidates the 1947/1950 “nine-dash line” which undergirds China’s expansionist claims to almost all of the South China Sea) and for other claimants as well. Contrary to the thinking of the appeasement bloc in the Philippine political class, the ruling is an enforceable decision—not because China will suddenly cave in under the weight of the legal ruling, but because China, the world’s second largest economy, is a signatory to many other international covenants and itself believes in the power of arbitration.

Defeatism is not a policy.