OP-ED OPINION: Time to consider the ICJ as China-PH next forum | BY FRANCISCO TATAD -The Manila Times

The Vietnamese government must have been pleasantly surprised when after apologizing for the incident last Sepember, in which two Vietnamese fishermen were killed while poaching inside Philippine waters, President Rodrigo Duterte last Wednesday personally sent off the five other illegal fishermen who had been arrested and detained after the incident. Indeed, the killing was regrettable, as every other killing is, but DU30 has never publicly apologized for any killing before, so Hanoi has every reason to be grateful.

Still we should not blame the Vietnamese if they were to regard DU30’s presence at the wharf in Sual, Pangasinan to personally say goodbye to the illegal fishermen as a sign of weakness rather than of magnanimity. It was totally uncharacteristic of the man and it had nothing to do with the requirements of statesmanship or diplomatic protocol. Neither the President nor the Prime Minister of Vietnam, nor the Vietnamese Ambassador in Manila, Ly Quoc Tuan, had expected it, and nothing in the relations between the two countries demanded it.

Ties with Vietnam

The Philippines has always been a good friend of Vietnam. During the Vietnam war, President Ferdinand Marcos hosted the Manila summit of the Vietnam war allies, but resisted all pressure from US President Lyndon Johnson to send combat troops to the war. Instead, he sent the non-combat Philippine Civic Action Group (Philcag), whose work is well remembered in Vietnam long after the war. The Philippines also became a halfway-house for boatloads of Vietnamese refugees trying to find their way to the United States.

Releasing the illegal fishermen from detention without any further obligations would have been more than sufficient. It would have shown DU30’s benevolence, in the name of the two countries partnership in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), whose 31st summit DU30 had just hosted in November, and Hanoi would have appreciated it. But to go beyond it was a bit too much, and could be misinterpreted to mean our lack of ability or preparedness to assert our own authority in our territorial waters.

This matter is something we need to be zealous about, especially in light of our country’s territorial and maritime dispute with China in the Spratlys. We cannot allow any outsider to say that while DU30 is unforgiving of those who criticize the killings in his war on drugs, he is so ready to look the other way in matters that involve our country’s sovereign and territorial rights.

Failing state

More and more people are inclined to call the Philippines a “failing state” precisely because of its demonstrated failure to protect its national territory from the incursions of others. This is not all they say about us. They also say the Philippine state has lost to certain armed groups—the CPP/NPA/NDF in various parts of the country, and the Muslim insurgents in the South—its lawful exclusive use of armed force to enforce its will and its laws, together with its sole power to impose taxes on business.

They further see that it has failed to guarantee the unquestioned legitimacy of its “elected” leaders because of questionable automated elections, even though these have not raised as much noise and scandal as the Democrats accusations of alleged Russian cyber-meddling in favor of US President Donald Trump in the 2016 US presidential elections. They regard human rights violations in DU30’s drug war as generally destructive of human security, as the highest national officials are heard to say, “criminals and drug addicts are not human beings,” and mere drug suspects are killed without due process or documentation.

But even if these other factors did not exist, the nation’s failure to assert its sovereign rights within its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), under the Law of the Sea, while others freely exercise their disputed “rights” to these areas without any impediment from the Philippine government— this alone would make it hard to brush aside the “failing state” label. For this reason, DU30 cannot afford to be dismissive of any violation of the country’s territorial waters, even if committed by a few harmless nationals of a friendly power. The state must protect its interests always from all parties, including its closest allies and friends.

The Chinese problem

This leads us back to our most important maritime and territorial issue, hich DU30 has decided to put in the back-burner—our maritime and territorial dispute with China in the South China Sea, described in one legal document as “a semi-enclosed sea in the Western Pacific Ocean, 3.5 million square kilometers in size, south of China, west of the Philippines, east of Vietnam, north of Malaysia, Brunei, Singapore and Indonesia. It is a crucial shipping lane through which passes $5 trillion worth of trade every year, a rich fishing ground, home to highly diverse coral reef ecosystem and believed to hold substantial oil and gas reserves.

The disputed areas lie in the Spratlys, described in the same document as “the constellation of small islands and coral reefs in the southern portion of the South China Sea, existing just above or below water, that comprise the peaks of undersea mountains rising from the ocean floor.”

In 2013, the B.S. Aquino 3rd government asked an Arbitral Tribunal, constituted under the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which the Philippines ratified on May 8, 1984 and China on June 7, 1996, and with 168 state parties, to resolve the dispute concerning maritime rights and entitlements in the South China Sea.

It took the position that China’s rights and entitlements must be based on the UNCLOS, not on any claim to historic rights. It argued that China’s claim to rights within the nine-dash line marked on Chinese maps are without lawful effect to the extent that they exceed the entitlements that China would be permitted by the Convention.

The Philippine petition

The Philippines asked the Tribunal to resolve the dispute concerning entitlements and maritime zones generated under the Convention by Scarborough Shoal and certain features in the Spratlys. It held that all of the features claimed by China are submerged banks or lowtide elevations incapable on their own of generating entitlements to maritime areas and cannot sustain human habitat or economic life of their own. They also do not generate an entitlement to an EEZ of 200 nautical miles or to a continental shelf.

The Philippines further asked the Tribunal to resolve disputes such as:

a) Chinese interference in the Philippine rights to fishing, oil exploration, navigation and construction of artificial islands and installations;

b) Destruction of the marine environment by harvesting endangered species and the use of destructive methods that damage the fragile ecosystem in the South China Sea;

c) Harm to the marine environment by constructing artificial islands and engaging in extensive land reclamation at Cuarteron Reef, Fiery Cross Reef, Gaven Reef, Johnson Reef, Hughes reef, Subi Reef and Mischief Reef—seven reefs—in the Spratlys;

d) China restricting access to a detachment of Philippine Marines stationed at Second Thomas Shoal and engaging in large-scale construction of artificial islands and reclamation at the seven reefs in the Spratlys.

China refused to recognize the process and the jurisdiction of the Tribunal. However, Article 9, Annex VII of the Convention, provides that “in the event of a dispute as to whether a court or tribunal has jurisdiction, the matter shall be settled by decision of that court or tribunal” and that “any decision rendered by a court of tribunal having jurisdiction under this section shall be final and shall be complied with by all the parties to the dispute.”

On Oct. 29, 2015, the Tribunal issued its award on jurisdiction and admissibility, paving the way for the Permanent Court of Arbitration to proceed. Five international judges were appointed, a panel of international lawyers represented the Philippines, and Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Japan and Australia sent observers to the hearings.

Arbitral ruling

On July 12, 2016 the Tribunal ruled in favor of the Philippines. It concluded that there was “no legal basis for China to claim historic rights to resources within the sea areas falling within the ‘nine-dash line’.” Having found that none of the features claimed by China was capable of generating an EEZ, the Tribunal found that it could—without defining a boundary—declare that certain sea areas are within the EEZ of the Philippines because those areas are not overlapped by any possible entitlement of China.

The Tribunal also said China violated the Philippines’ sovereign rights, its claim beyond 200 nautical miles from its mainland coasts being far beyond the limits of its EEZ and continental shelf entitlements. It found that China, through its toleration and protection of and failure to prevent Chinese fishing vessels engaging in harmful harvesting activities of endangered species at Scarborough Shoal, Second Thomas Shoal and other features in the Spratlys, breached Articles 192 and 194 (5) of the Convention.

It further found that China, through its island-building activities at the seven reefs, breached several articles of the Convention. Chinese reclamation is believed to have added 5,580,00 square meters of land to Mischief Reef as of November 2015, plus fortified seawalls, temporary loading piers, cement plants and a 25-meter wide channel to allow large vessels to transit into the lagoon. Some 3,000 meters of land has been flattened along the northern rim of the reef for a possible airstrip, according to reports.

Mischief Reef lies within the Philippine EEZ, and it’s a low-tide elevation, which generates no entitlement or maritime zone of its own. It is beyond dispute that China has appropriated the reef for its own. It is also established that China expanded its island-building activities while the work of the Tribunal was in progress, and after it issued the ruling. But without any enforcement mechanism, the Tribunal could rely only on the good faith of the Parties to comply with the ruling.

China decided to permanently reject the ruling.

That was expected of China. What was not expected of DU30 was his decision to not even refer to the ruling in his talks with Chinese President Xi Jinping and other Chinese officials. He could have at least said, “The Permanent Arbitration Court has ruled on our petition, but we are not going to talk about it now, nor allow it to burden the course of our future relations.” That would have at least put the Chinese government on notice that the Philippine President was still talking for and on behalf of the Philippine government.

Although the Philippine legal panel had asked the Tribunal to ask China to do what the Convention obliges it to do, DU30’s decision not to disturb relations with Beijing with any mention of the ruling completely neutered his government’s right to seek a peaceful settlement of its dispute with Beijing. This is not an easily forgivable offense.

What DU30 can do now

But now that DU30 has gained the trust and confidence of the Chinese, it is time for him to propose that the Philippines and China agree to submit their territorial dispute to the International Court of Justice, without disturbing their friendship and good neighborly relations, just as Singapore and Malaysia, and Indonesia and Malaysia have done. Consistent with its status as an economic and political power, China has to become a great pillar of international law, and DU30 as President Xi’s foremost friend and champion should be among the first to help him.

CORRECTION: In my Dec. 1 column, the correct name of the Archbishop of Davao and new CBCP President is Most Rev. Romulo Valles, not Romeo Valles.

.

Published

ASEAN NEWSPAPER OPINIONS AND EDITORIALS

.

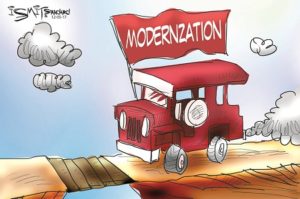

7.2. Jeepney drivers, operators make a final appeal– The Manila Bulletin

.

.

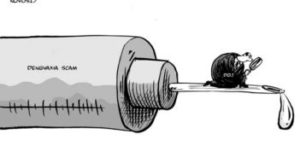

7.4. DENGVAXIA SCAM – The Manila Times

.7.5. Complex and delicate matter – Philippine Daily Inquirer

.7.6. Complex and delicate matter– The Philippine Star

<>NOTE : All photographs, news, editorials, opinions, information, data, others have been taken from the Internet ..aseanews.net | [email protected] |

For comments, Email to :

D’Equalizer | [email protected] | Contributor