US IMMIGRATION: USA – Who gets to dream? America’s immigration battles go beyond walls and borders

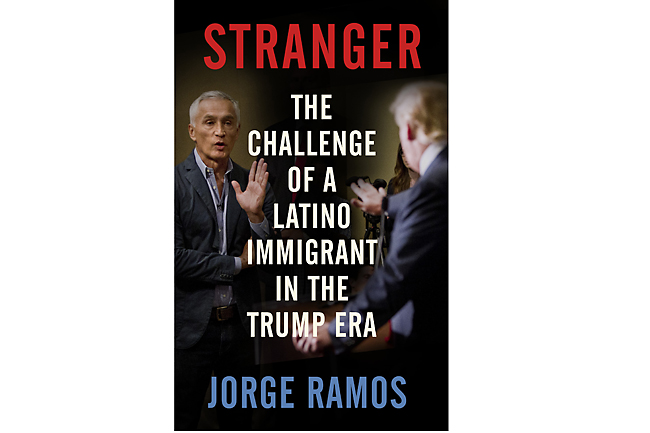

Stranger by Jorge Ramos. – PHOTOS: WP-BLOOM

MY FATHER is a dreamer. He dreamed of America, of having his children grow up here, even though it meant trading a decent existence in Peru for a harder path. My mother dreamed, too, mainly of returning, which we did, often enough that, in whatever place I was, I dreamed of the other.

It is the lot of the immigrant to straddle borders of all kinds at all times; we gaze back with nostalgia and relief, we look forward with boundlessness and insecurity, we strive to belong even when we get the hint. “It’s impossible to be just one thing at a time,” writes Univision’s Jorge Ramos in his new book, “Stranger,” a blend of memoir, analysis and manifesto. “Immigrants understand that they are many things at once. We don’t have a solid, immutable identity. Over the span of a single day, I can feel Latino, Mexican, American, foreigner, and newcomer.”

Ramos dedicated his slim book to “The Dreamers, my heroes,” a bow to the students turned activists seeking legal protections for themselves and others like them who entered the United States unlawfully as children – who arrived here, as the obligatory qualification goes, through no fault of their own. But if not their fault, whose? The blame usually falls on their parents, who dared to dream on their behalf. Those elders are the “sacrificial generation,” Ramos writes, often unable to legalise their own status but quietly staying so their children might prosper.

This divide between old and young, between caution and daring, cleaves through the heart of the Dream Act and the cause of immigration reform, separating families and classes and undercutting immigrants’ collective voice. In “The Making of a Dream,” journalist Laura Wides-Muñoz spends a decade following this generation of young activists as they attempt to sway Washington and public opinion.

“These teens refused to become ghosts, to hide as their elders had,” she explains. Yet their cultural clout has yielded only legislative frustration and a precarious future, as the fate of an Obama-era programme, known as DACA, protecting them from deportation has been enmeshed and postponed amid battles over government funding, court rulings and President Trump’s demand for billions of dollars to secure the US-Mexico border.

.

“I don’t know if the border is a place for me to understand myself, but I know there’s something here I can’t look away from,” Francisco Cantú writes in “The Line Becomes a River,” a memoir of his time as a US Border Patrol agent, guarding the same boundaries that his Mexican grandfather crossed long ago and that the American president now pledges to defend with a wall. Cantú’s understated yet searing chronicle mixes history, family, duty and dreams as well, except his are nightmares of violence and guilt.

“Americans are dreamers, too,” Trump declared in his State of the Union speech, slyly seeking to wrest moral authority away from the young immigrants claiming it. Together these works loom as floodlights over contested territory, illuminating immigration as a state of mind, a generational dispute, a legal battle. And they help show why, in the land of the American Dream, dreaming itself has become politicised, a partisan battleground over rights and self-definition.

It is ironic that the “dreamers” – now ranging from their teens to their 30s – would become tied in the public imagination to a proposal that arrived years ago but has yet to achieve full legal status. The Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors Act has been around since 2001 and reintroduced, to no avail, on multiple occasions.

The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals programme, launched in 2012 and set to end next month, has some 690,000 participants formally enrolled, a small slice of the total undocumented population, estimated at about 11 million.

Yet its potential beneficiaries have become the face of America’s immigration debate. They are the young, the educated and the promising. Their early advocacy invariably featured caps and gowns.

It is an appealing picture but one that tends to crop out the nannies, the gardeners, the food service workers and, of course, the old. Even as he is inspired by the dreamers, Ramos worries about generational rifts. “After many conversations with the Dreamers and their parents, I began to notice a certain sense of impatience among the Dreamers,” he writes.

“Why had their parents remained silent for so long? Why did they not speak up and protest? Why didn’t they go out and fight for their rights?”

Ramos knows something about such conflicts; he departed Mexico in 1983 at age 24, leaving not just an authoritarian government but an authoritarian father as well.

But Wides-Muñoz probes deep into the dreamers’ relationships with their parents and often finds empathy and concern. One of her most memorable characters is Marie Gonzalez, who left Costa Rica with her parents in 1991, at age five, eventually settling in Missouri.

When Marie becomes one of the early Dream Act advocates, travelling to Washington, giving speeches and radio interviews, she is constantly asked about the plight of young people like her.

“A hard knot tightened in her stomach,” Wides-Muñoz writes. “Don’t forget about my parents, she wanted, but was afraid, to say.” By centring solely on her own story, Marie felt “as though she was betraying those she loved most.” She survived a deportation order, but her parents didn’t.

The tensions surface not just within families but among activists. Older immigration advocates preferred comprehensive reforms over a law that would help only a particular cohort of the undocumented. Still, they grasped that “the moral authority these young immigrant students wielded before lawmakers was unmatched.” The dreamers, for their part, grew restless in their role. “Increasingly, they felt as if the older activists viewed them as props, trotting them out to pull at the heartstrings and then sending them back to their seats,” Wides-Muñoz writes. One longtime activist even encouraged Marie to cry in an interview, which she did, mainly out of anger and frustration. (“Why did she need to show those officials weakness?” she asked herself.)

Even the four dreamers who walked the 1,500-mile “Trail of Dreams” from Miami to Washington in 2010, in what became the movement’s signature action, found disillusion at journey’s end.

“They had gained national and international attention, winning the respect of many of the naysayers,” Wides-Muñoz writes. “Yet back in the nation’s capital, they were once again at the mercy of the Washington players.”

The author also cites young immigrants who arrived too late, or too old, to be covered by a potential Dream Act. Alex Aldana, who had come from Mexico with his family at age 16 in 2003, grew to resent the attention lavished on the “valedictorian types” by journalists, activists and lawmakers.

“He wished he could see more young people like himself testifying in Congress,” Wides-Muñoz writes, “those who weren’t stars but who were working to support their families and contributing to the economy.”

Even for those who would benefit from it, the Dream Act has been cursed by nightmarish timing. An early congressional hearing on the bill was scheduled for September 12, 2001.

During the Obama years, the proposal was pushed aside for health-care reform and fiscal stimulus, despite Barack Obama’s campaign promise – in an interview with Ramos – of an immigration bill during his first year in office.

On the same day in 2010 that the Senate voted to end the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy, which had barred LGBT people from serving openly in the military, the Dream Act fell five votes short of the threshold needed to be considered for final passage. More recently, Trump’s quest for a border wall seems to render the legislation even less likely.

Yet the Dream Act’s failures have in some way liberated the dreamers from the image that lawmakers and activists forced on them. “Presenting the story of the perfect, well-mannered students hadn’t worked,” Wides-Muñoz writes. “Now they could just be human.”

Humanity is the preoccupation of “The Line Becomes a River” – recognising it, acknowledging it, salvaging it. After studying immigration in college, Cantú convinced himself that joining the Border Patrol would be one more step in his education, even as his mother warned that he would be absorbed by a system “with little regard for people,” that “the soul can buckle” in such a job.

In his initial training sessions, a supervisor assures him that not everyone trying to cross the line is just another good person seeking honest work, that there are, as Trump would later put it, some bad hombres coming, too.

“Did you ever arrest a narco?” a friend asks him breathlessly. He did snag a few lower-level smugglers, scouts and mules, “but mostly I arrested migrants,” Cantú admits. “People looking for a better life.”

Cantú struggles to make those lives a little better even as he detains and processes border crossers, slashing their water bottles and ransacking their supplies to discourage them from going further.

Cantú gives his shirt to a man who had lost his own and treats him to burgers on the way to the station. He warns two teenage boys not to attempt to cross the border again in the summertime; it is too hot and dangerous. He treats and bandages the blistered feet of a woman who had been left behind by a group of border crossers because of her limp – a “quitter,” in the patrol’s parlance. “Eres muy humanitario, oficial,” she tells him. “No,” he says, looking down at her feet. “I’m not.”

After four years on the job, Cantú leaves it in 2012, but he finds it does not leave him. “It’s like I’m still a part of this thing that crushes,” he tells his mother. Later, while working at a coffee shop, he befriends an undocumented co-worker named José, who is caught by the Border Patrol after attempting to return from Mexico, where he had been visiting his ailing mother.

Cantú takes José’s family – including the man’s young US-born children – to witness his courtroom proceedings and to visit him in a detention facility. He helps José’s wife, Lupe, gather the paperwork needed for a lawyer to make a doomed case for “prosecutorial discretion” – essentially, hoping that a judge will offer José a stay of removal. – WP-BLOOM / Borneo Bulletin /

.

NOTE All photographs, news, editorials, opinions, information, data, others have been taken from the Internet ..aseanews.net | [email protected] |For comments, Email to : JARED PITT | [email protected] | Contributor