ASEAN ARTS+CULTURE: The Nurturer – Leo Abaya on Cultivating the Seeds of Creativity -By Hannah Jo Uy

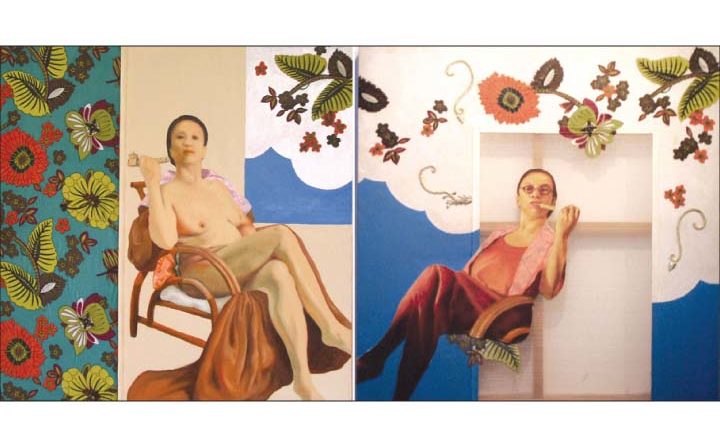

‘Junto a las Flores ja las Major, 2008’ Portrait by Pinggot Zulueta

.

“My biological life is tied with my creative life,” said Leo Abaya. “I need to inquire, create, and discover to keep me alive.” As a multi-disciplinary visual artist, Abaya has had critical and commercial success with an oeuvre that has delighted audiences locally and abroad. While Abaya recognizes the role external affirmations play in pushing his creative boundaries, it is of secondary concern to the artist because it is, as he describes it, “time consuming.” “There are other occupations and disciplines that are devoted to expertise in those matters,” he commented.

.

.

Aboard Argo Navis

Aboard Argo Navis

.

But for a craft that filters the beautiful and the interesting to develop something meaningful and innately human, Abaya has a self-awareness reflected in both his process and output. “I’m like a gardener with many seeds before me,” he said. “The seeds I know of, familiar with and accustomed to, I plant and nurture in the usual way, but regularly experimenting and stretching limits. Some unfamiliar seeds I plant and cultivate, guided by the methods of other gardeners who have experienced cultivating them: be guided by not thoughtlessly follow. And then at a certain point, it’s gut feel. Pakiramdam. I delight in the cultivation more than the harvest.”

Admittedly, Abaya said, some aspects of his art require methodical deliberation, and others yet, spontaneous exertion. “I try my best to respond accordingly,” he shared. From the beginning, however, Abaya confesses a deep interest in identity and “its different permutations and problems.” “My interest in the body,” he said, “while not exclusive is closely linked to it. Histories interest me not for nostalgia but that it makes me think more, if not critically, of the present.”

,

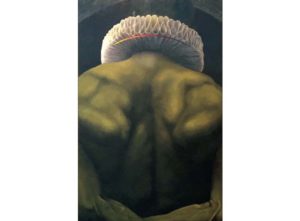

Panginoong Alipin – Papuri kay Zakil ( Master Slave – In Praie of Zakin, 2016)

This he said, becomes processed in a myriad of different ways, following the rich assortment of experiences that shape and mould his mindset. Abaya’s ability to give himself over to the creative process is embodied by his expertise in many aspects within visual arts, from painting, drawing, set design to filmmaking, all of which are equal in his eyes. “I just know I am drawn to the visual as something to ponder on and make,” he said, “and interestingly as a reason or motivation to be verbal in the written and oral sense.”

The diversity in which Abaya chooses to express himself has imbibed his work with a strong eclectic flavor “where style, distinguishable iconography or singularity in medium takes a backseat.” While Abaya does not profess to make art in a swift manner, the sensibility, he said, is there when one looks closely.

.

.

Points of View, 1993

Sharing observations gleaned since exhibiting in the ’90s, Abaya said general interest in the visual arts did not evolve in a drastic manner as even then it was a thriving market with exhibitions heavily attended though collectors were far and few in between. “The increase in interest today,” he commented, “is proportionate to the increase in awareness that came with the internet, which to my mind is one of the factors in the increased interest in collecting and in art in general.”

.

Abaya said that that with the shortcut that the internet media provides in terms of social visibility, the collector and the artist dynamics have positively impacted the primary market and its agencies. “The secondary market too is profiting from it,” he said. “The museums have been revitalized for some years now through or because of it. Artist initiatives and communities have become more visible to the public consciousness for similar reasons.” In this manner, Abaya said, interest in art of late has evolved from the past and is clearly and more concretely translated into economic and cultural exchange as well as discourse between and among artists, curators, academics, collectors, the market, and cultural institutions including non-institutional communities such as artist collectives.

Abaya’s postgraduate education abroad and experience as an exhibiting artist urged him to examine his practice in terms of a deeper awareness that materials and processes “not simply a means to an end but are part and parcel of one’s content such that meaning can be derived and communicated from it; that subject, iconography, technique, and style are not all and end all for me.” In addition, Abaya said, his experiences opened him to theory, which affirms, tests and challenges his subject position as an artist. “As a viewer of art,” he said, “travel and international exposure gives one an appreciation of the range of visual art coming from diverse philosophies, ideologies, and cultures. I’ve realized that the young do not have the monopoly of fresh ideas and visual approaches.”

From what he has seen, Abaya said, maturity is important in art making and the freshest ideas are largely borne from considerable experience in the practice, particularly to the artists who are little known but well respected. “I am also keenly aware that long practice can also tempt the contented artist to resort to formula,” he said. “And I have seen this demonstrated as well, here and there.”

For his part, Abaya said, the biggest challenge is how to remain committed to artistic creation without shirking from social responsibility. “Equally,” he added, “how to make a meaningful contribution to culture without expecting public recognition or institutional reward.” But throughout these reflections on his chosen profession, Abaya said, simply, “I create and live. I create or die.”

By Hannah Jo Uy . / Manila Bulletin / Published