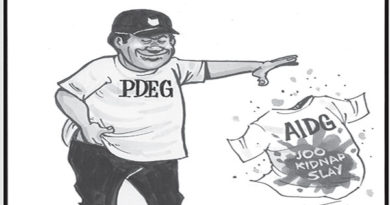

REALTY-CONSTRUCTION | Ayala Land | SkyCity Tower, EDSA corner of Ortigas Avenue, Brgy. Wack Wack Greenhill East, 77-story mixed-use building with an eight-story basement on 4,109 square meters lot

This Is the Story of That Big Hole in EDSA-Ortigas

You must have seen it if you’ve ever traveled through EDSA.

.

If you’ve ever spent any time traversing EDSA Southbound from Quezon City to Makati, you’re no doubt familiar with that giant gaping hole in the ground at the corner of Ortigas Avenue. People who ride the MRT, especially, get a much better view of that deep pit right across from Robinsons Galleria and the POEA (Philippine Overseas Employment Administration) building.

Top Story: Transwoman Billionaire Wants Clint Bondad to End Drama, Reveals Clint is Living With Her

That hole, which is now overrun with moss and vegetation, has been the subject of speculation for years. Why is it there? The land is pretty valuable, and somebody obviously tried to build something there. What happened?

Well we at Esquire did some, er, digging (get it?!) to get to the bottom (we’re on a roll!) of things. Here’s what we found.

>

Ad by:

Memento Maxima Digital Marketing

@[email protected]

SPACE RESERVE FOR ADVERTISEMENT

.

Where is it exactly

First of all, while some people assume the area is already under San Juan, it’s actually in Brgy. Wack Wack, which means it falls under the jurisdiction of Mandaluyong. Years ago, there was a Tropical Hut restaurant on that land, and the only thing close to being a “skyscraper” in the area was the nearby Securities and Exchange Commission building.

In the mid-1990s, the lot owner, a company called San Buena Realty and Development Corp., partnered with E. Ganzon Inc (EGI) to develop the land. The site measures 4,109 square meters and the idea was to build a 77-story mixed-use building with an eight-story basement. It was going to have a hotel, luxury residential units, and a bar right at the top. The project was to be called SkyCity Tower, and the developers had dreams of it being the tallest building in the country.

In April 1997, EGI fenced the land and demolished the structures on it. It also began excavating the ground in order to start laying the foundation. But according to court records, the company did so without first obtaining a barangay permit to dig.

Still, EGI moved fast. On July 10 of the same year, the company secured a Certificate of Locational Viability from the Housing and Land Use Regulatory Board (HLURB); a month later, on August 11, the City of Mandaluyong issued an Excavation and Ground Preparation permit. And on September 15, 1997 the HLURB further issued a Preliminary Approval and Locational Clearance for the project.

>

Ad by:

Memento Maxima Digital Marketing

@[email protected]

SPACE RESERVE FOR ADVERTISEMENT

.

Homeowners complain

While all this was going on, the homeowners association of Greenhills East Subdivision, the residential subdivision that lies directly west of the property, voiced opposition to the project. The Greenhills East Association Inc., (GEA) brought up numerous complaints against the planned development—that it would violate the privacy of the residents, that it would threaten their water supply, and reportedly, that the building would cast a huge shadow on the homes, among other issues.

In January 1998, the GEA first wrote the National Capital Region office of the HLURB to formally oppose the project. It also filed a separate complaint letter to the Department of Public Works and Highways.

This was the beginning of a lengthy legal battle between GEA and EGI that essentially stalled the project. After the HLURB arbiter dismissed GEA’s opposition to the project, the GEA filed a petition for review, which was denied, and a motion for reconsideration, which, again, was also denied.

On November 2001, the GEA took its case to the Office of the President, which, after years of back-and-forth, denied the appeal on a technicality. After a motion for reconsideration was also denied, the GEA filed a motion for review of the OP’s orders with the Court of Appeals. The CA denied this petition as well as another motion for reconsideration.

The GEA’s final recourse was the Supreme Court. On January 10, 2010, the SC rendered its verdict affirming the decision of the Court of Appeals. Because the issues raised were factual, the Court said in its decision that it would defer to the expertise of the HLURB.

“The Court cannot find fault in HLURB’s assertion that the real test of whether a land use serves the need of a district is not in the size or height of the buildings but in the sufficiency or surplus of the business or human activities in a given district to which they cater,” Supreme Court Justice Roberto Abad says in the decision. “Land use is affected by the intensity of such activities. Extraordinary population density or overcrowding, brought about by competition for space in the scarce area of the district, is to be avoided. Using this test, the HLURB, which is the clearing house for efficient land use, found no clear showing that respondent EGI’s project if finished would cause havoc in the population level of the land district where the project lies.

“What is more, the houses of petitioner GEA’s members are separated by fences and guarded gates from the adjacent areas outside their subdivision,” Justice Abad writes further. “Their exclusiveness amply protects their yen for greater space than the rest of the people of the metropolis outside their enclave can hope for. Respondent EGI’s project offers no threat to the subdivision’s privacy. It is on the other side of the fence, wholly unconnected to the workings within the subdivision. The new building would be in the stream of human traffic that passes EDSA and Ortigas Avenue. Consequently, it would largely attract people whose primary activities connect to those wide avenues. It would seem unreasonable for petitioner GEA to dictate on property owners outside their gates how they should use their lands if such use is not in contravention of law.”

Two months later, on March 10, 2010, the SC upheld its decision and ruled with finality: the SkyCity project can legally push through.

“The proponent, E Ganzon, Inc. hopes that its oppositors would now cooperate to realize the project which had unduly been delayed to the prejudice of its developer, the livelihood of those it stands to benefit during the interim, and the Filipino people in general who had been deprived of doing business in an environmentally friendly building because of their opposition,” Bienvenido G. de Castro, EGI vice president for external affairs said about the decision.

What happened next

Twelve years since EGI started work on SkyCity, it finally won its case against GEA. But what happened? Why didn’t EGI go full steam ahead on construction, now that there weren’t any legal impediments?

It seems the problem, as in many other cases, lies in funding. By 2005, the company had reportedly already lost P500 million over the 10-year delay of the project. A BusinessWorld story from 2005 said proponents of the project hoped “to be able to to reactivate funding sources for the project, originally set to be built via supplier’s credit and the Bank of China.”

EGI also announced back then that it was considering offering up shares to the public via an initial public offering at the Philippine Stock Exchange in order to raise funds for the project. But that IPO never happened.

Preliminary projections had the building costing about P5 billion, but with “spiraling cost of construction” and, presumably, the extended delays, estimates ballooned to P7 billion. Did the company simply run out of money? We can’t say for sure.

A Wikipedia entry about SkyCity says that Ayala Land had acquired the property from EGI in 2015, but we couldn’t independently confirm the veracity of this report.

Various other sources say the project is still “active” but no new updates have been posted about SkyCity Tower for years. And yes, that big hole in Ortigas is still there.