OP ED-OPINION | ACADEMIA- Tensions in South China Sea continue, but ASEAN successfully resolves maritime disputes

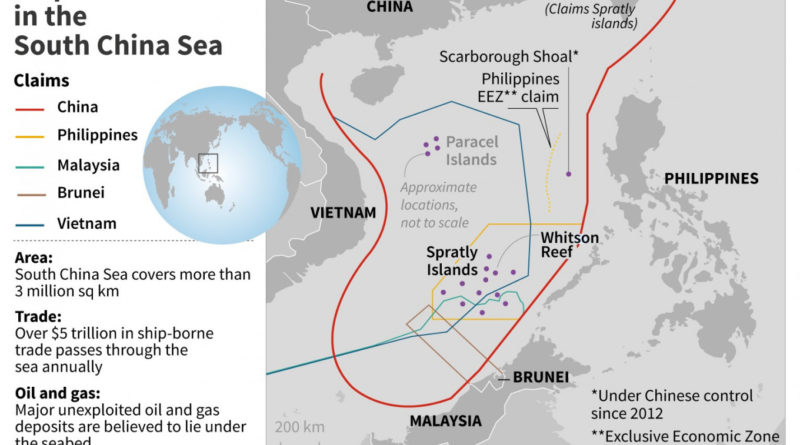

Disputed claims in South China Sea. ( CSIS/AMTI/D.Rosenberg/MiddleburyCollege/HarvardAsiaQuarterly/Phil govt/ChinaMaritimeSafetyAdministration/AFP)

Bec Strating and Troy Lee-Brown

Melbourne, Australia

In a flurry of late-April private talks, Filipino diplomats challenged officials from China over the recent pattern of assertive behavior from Chinese vessels in the South China Sea. The behavior by the Chinese included the early-February targeting of a Philippine Coast Guard ship with a military-grade laser near a disputed shoal and in late-March a Chinese vessel purportedly came within 10 meters of a Vietnamese Fisheries Surveillance vessel while inside Vietnam’s Exclusive Economic Zone.

Unfortunately for the Philippines and Vietnam, these instances of Chinese assertions within their claimed EEZ have become increasingly common, including the use of coastguard and fishing vessels to harass other vessels for strategic advantage.

This type of “grey zone” tactic has increased following China’s rapid artificial island building campaign in the South China Sea and the ruling of the international arbitral tribunal under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in favor of the Philippines on most of its submissions in its dispute against China in 2016.

For other South China Sea claimant states that similarly reject Beijing’s so-called “nine-dash-line”, such as Indonesia, tensions over disputed maritime boundaries continue to permeate their respective relationships with Beijing.

While the prominent nine-dash-line disputes in the South China Sea capture most of the region’s attention, there are also examples of Southeast Asian states resolving maritime boundary disputes in positive signs for regional maritime order centered on UNCLOS.

In December 2022, Indonesia and Vietnam concluded an agreement on their respective EEZ boundaries in the South China Sea, after 12 years of negotiation. Clarifying maritime borders may help resolve some of the ongoing issues of illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing between ASEAN countries. Indonesia, for instance, recently captured six fishing vessels flying Philippine and Vietnam flags allegedly fishing illegally around Sulawesi and Natuna Islands.

A key feature of intra-ASEAN maritime security problems and maritime disputes is that they are not a consequence of aggressive foreign policies that undermine key provisions in UNCLOS, unlike the way that China’s nine-dash line might be interpreted. For the most part, coastal Southeast Asian states have sought to deal with ongoing boundary issues by seeking not to intensify tensions—for example, through avoiding activities in contested zones, by creating provisional arrangements to share resources (such as in the Gulf of Thailand), or, in rarer cases, through international courts or arbitrations.

In July 2003, Malaysia instituted proceedings in the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea against Singapore’s land reclamation activities, arguing that Singapore’s extension of the Tuas port impinged on its rights in and around the Straits of Johor. In 2019 a breakthrough emerged when the two states bilaterally negotiated to suspend the expansions of their port limits.

In April 2016, Timor-Leste initiated the world’s first UN Compulsory Conciliation to resolve disputes over maritime boundaries and hydrocarbon reserves in the Timor Sea. At first reluctant to engage in international litigation, Australia was compelled to change its stance. A maritime boundary treaty between Australia and Timor-Leste was signed in 2018 reflecting a shift in Australia’s foreign policy approach towards the Timor Sea. In particular, the boundary line they devised managed to avoid Indonesia becoming involved in the dispute, mainly due to Australia’s concerns about unravelling its continental shelf boundaries.

Even Myanmar, often considered a regional destabilizer, resolved a maritime boundary dispute with Bangladesh in the Bay of Bengal through the use of the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea mechanism, with a ruling handed down in March 2012.

The successful and timely resolution of all regional maritime disputes are important to claimant states and the broader region, especially as geopolitical tensions in maritime Southeast Asia remain acute. Successful examples of maritime diplomacy help to maintain order, clarify jurisdictional rights and responsibilities, enable states to access their maritime rights under international law, and facilitate broader cooperation to counter contestation and uncertainty in key maritime domains.

***

Bec Strating is the director of La Trobe Asia and an associate professor of politics and international relations at La Trobe University, Melbourne. Troy Lee-Brown is a fellow at Defence and Security Institute, University of Western Australia. This article is part of a series of ‘Blue Security’ articles published with Melbourne Asia Review, Asia Institute, University of Melbourne.

.

Ads by: Memento Maxima Digital Marketing

Ads by: Memento Maxima Digital Marketing

@[email protected]

SPACE RESERVE FOR ADVERTISTMENT

Memento Maxima Digital Marketing

Memento Maxima Digital Marketing