INDONESIA MIGRANT WORKERS LABOR : LEGAL PROTECTION FOR INDONESIAN MIGRANT WORKERS ABROAD

.Jakarta. It is not uncommon to see stories of Indonesian migrant workers grazing headlines on both mainstream and social media, many of which contain unfortunate details describing experiences of being overworked, physically abused, trafficked or facing the death penalty.

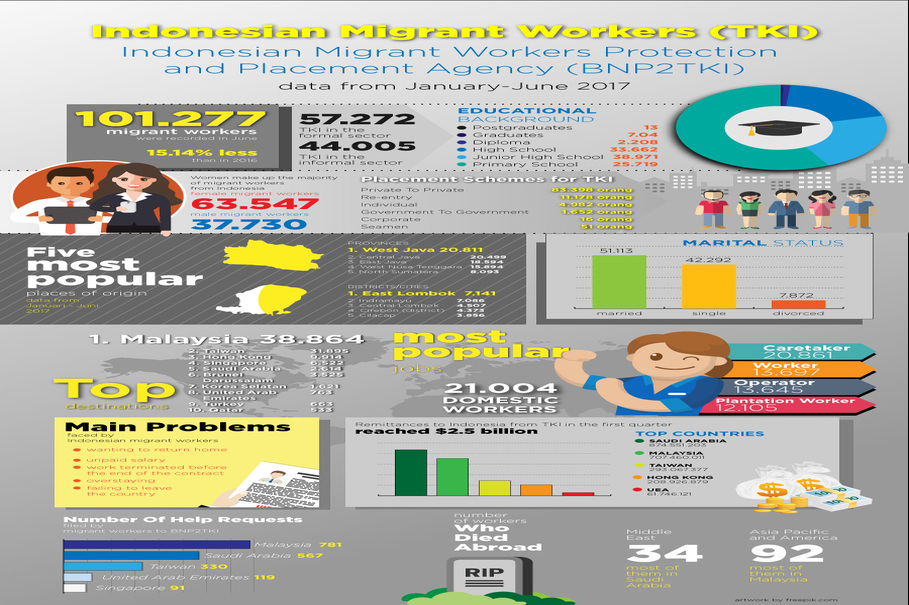

Such is the plight of many Indonesian migrant workers abroad, who number around 6 million and who send billions of dollars in remittances home every year.

Still, Indonesia’s current laws and regulations concerning migrant workers lack an imperative focus on their rights to protection and fulfillment, revealing yet another example of many shortcomings in the country’s regulatory system and the need for reform.

Indonesia declared its commitment to protect and promote the rights of migrant workers in September 2004, when it signed the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families.

The government finally ratified the convention in May 2012 and is currently formulating a draft amendment on the 2004 Law on the Placement and the Protection of Indonesian Migrant Workers.

The country seeks to harmonize the law with provisions in the Convention, part of the government’s top legislative priorities this year. After all, protecting and providing a safe environment for all citizens is also part of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s Nine Government Priorities, or Nawa Cita, for the period 2015-19.

.

Is It Enough?

Indonesia relies on several memoranda of understanding with countries, such as Saudi Arabia, South Korea and Qatar, which dictate terms of employment conditions for its migrant workers.

These instruments play a crucial role in protecting Indonesian migrant workers, as many of their destination countries have neither signed, nor ratified the International Convention.

“Not all memoranda of understanding between Indonesia and destination countries reflected the human rights provisions of the Convention,” Anis Hidayah, chairwoman of Migrant Care’s migration study center, said during the 27th session of the Committee of the Protection of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families in Geneva, Switzerland, earlier this month.

Anis noted that factors such as minimum age and working hours were omitted from existing bilateral documents, and said that “almost all of the MoU did not include rights of migrant workers, with understandings [between countries] mostly based off mutually beneficial agreements and [which do not include] respect for human rights.”

Indonesia has yet to renew its expired memorandum of understanding with Malaysia, despite the fact that the neighboring country is a key destinations for migrant workers from the archipelago. This has led to almost 700 cases of undocumented migrant workers in 2017 alone.

Currently, only 13 memorandums have been signed with destination countries, Anis added, whereas Indonesian workers can be found in at least 180 countries.

Savitri Wisnuwardhani, the national secretary of the Migrant Workers Network (JBM), said during a press conference prior to the UN meeting in Geneva that the government’s efforts to realize the protection and fulfillment of the rights of migrant workers still lacks serious commitment.

Abdul Wahab Bangkona, special adviser to the manpower minister, said the 2004 law revision, which is now in its final stages, represented “monumental progress” for Indonesian migrant worker protection. Abdul highlighted that the revision now takes into account the protection of migrant workers and reflects Indonesia’s efforts “beyond the Convention” as it also regulates empowerment for workers’ families still based in the country.

Private Agency Monopoly

Existing law has yet to incorporate the government’s role in ensuring the protection of migrant workers, thus exposing their vulnerability to human rights abuses and trafficking.

Under the 2004 law, private recruitment agencies were granted a wide scope of authority from recruitment, processing of documents, pre-departure training, protection during employment and addressing issues experienced by workers.

Daniel Awigra, a program manager at the Jakarta-based Human Rights Working Group (HRWG), said in a statement that latest draft revisions of the law still favored a monopoly of private recruitment agencies to handle employment for would-be migrant workers.

“Private recruitment agencies don’t incorporate a standard in their recruitment process, which should cover a curriculum and basic skills for potential migrant workers. This usually leads to overcharging, which is borne by the migrant worker, and if any case comes up against the worker, most of these agencies don’t want to get involved,” Daniel said.

.

The National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komnas Perempuan) highlighted that migration costs must be regulated clearly in the revised bill, and that the burden, which includes passport and insurance fees as well as the costs for training and transportation, can be divided among workers, the government, employers and recruitment agencies.

Whether the revised law will fully address and improve the issues associated with the existing recruitment system is not yet clear, shifting years of practice that prioritized placement over protection will surely take time and must be emphasized through good governance and effective law enforcement.

Dewi Aryani, a member of House of Representatives Commission IX, said “it’s time that BNP2TKI launch their offices in migrant workers’ destination countries, like Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar and Hong Kong,” referring to the country’s National Board for Placement and Protection of Indonesian Overseas Workers.

According to Dewi, these offices can be integrated with existing embassies or consulate offices and should be utilized to keep and maintain a database of migrant workers.

Domestic Workers’ Rights

With more than 80 percent of Indonesian migrant workers employed as domestic workers – the majority of whom are women – one of the challenges that Indonesia must face is how to improve domestic workers’ labor and social rights.

Many domestic migrant workers face the struggle of long working hours, being cut off from the outside world and lack reasonable wages, while others are subjected to physical or psychological abuse.

The story of Erwiana Sulistyaningsih, which garnered international attention in 2014, is a prime example of the extent to which abuses are often perpetrated against domestic workers and further illustrates the importance of a legal instrument to protect them. Erwiana was found at the Hong Kong International Airport covered in burns and scars inflicted by her employer, Law Wan-tung, who was eventually sentenced to six years in prison.

But Indonesia has yet to ratify International Labor Organization Convention No. 189 on Domestic Workers, further complicating the country’s efforts to expand protection to domestic workers abroad.

While nongovernmental organizations, including Komnas Perempuan and HRWG, have recommended that the provisions included in the ILO Convention be included in the new bill on migrant workers, the government’s seeming reluctance to ratify that convention may mean that ensuring decent work for domestic workers is only a secondary priority for the Jokowi administration.

The government said it is currently conducting a study and review on the content of the convention in the country’s report to the UN committee in Geneva earlier this month, and noted that the study “takes into account cultural values that are still highly being upheld by the Indonesian people,” in reference to the “principle of kinship and familial” without further elaborating on how those values relate to ensuring the rights of domestic workers.

Economic Contribution

In Indonesia’s pursuit toward more sustainable economic growth, granting protection to migrant workers would constitute a far-reaching policy initiative that would benefit many facets of society in the country.

Recent data from BNP2TKI shows that Indonesian migrant workers sent home $4.32 billion in remittances in the first half of 2017. In comparison, the country booked $6.8 billion in goods and services net trade surplus in the same period.

The case for migrant remittances to their countries of origin remains high, as they “represent a major vehicle for reducing the scale and severity of poverty” and are “associated with greater human development outcomes across a number of areas such as health, education and gender equality,” according to a policy brief published by the Migration Policy Institute.

Migrant workers face complex challenges, from the threat of the death penalty, lack of assistance in the fulfillment of their constitutionally protected political rights abroad, to a lack of protection for ship crews operating in international waters.

Indonesia’s recent report to the UN committee in Geneva showcases the government’s comprehension of the issues faced by migrant workers, and showed – both to the international community and to its own citizens – that the country has commitments to ensure that human rights will be enjoyed by all Indonesians, including those outside the country.

Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi declared during the 27th Session of the UN Universal Periodic Review in Geneva in May that “human rights is part of our DNA as a democratic, pluralist and diverse nation.”

Amid Jokowi’s ambitious plans to develop the country, realizing the government’s commitment to uphold human rights for all citizens poses a grand and challenging task, which may require active participation from ordinary Indonesians as well as collaboration with and support from civil society for those goals to be truly realized.

.

Migrant Workers’ Rights in Asean

As part of its foreign policy, Indonesia has pushed for a legal instrument on the protection of migrant workers within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) and has continued to urge universal ratification of the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, according to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Manpower Minister Hanif Dhakiri met with his Philippine counterpart, Silvestre Bello, in Jakarta in August to discuss instruments of protection and ways to promote rights of migrant workers in the region.

For countries such as Indonesia and the Philippines, undocumented migrant workers are considered a human rights issue. However, destination countries such as Malaysia and Singapore remain firm that migrant workers pose threats to their national security.

During the meeting, Indonesia and the Philippines agreed to increase dialogue among sending and receiving countries in order to facilitate information-sharing and skills acknowledgment, among other things.

The bilateral meeting reflects one of the many discussions among Asean member states – bilaterally and multilaterally – with the aim to reach a consensus on an instrument of migrant workers’ protection, which are expected to be adopted during the upcoming Asean summit in November.

A decade after the 2007 Cebu Declaration, which mandates the pursuit of a regional instrument to protect migrant workers, the push among Asean sending states for a legally binding instrument has not yet been well received by destination countries that insist on instituting non-legally binding guidelines.

The issue of undocumented migrant workers and the inclusion of their family members in the instrument are also the focus of ongoing discussions, and the stark divergence between sending and receiving states often results in failure to reach a broad consensus on the issue.

Courtesy: The Jakarta Globe – Sheany

Additional reporting by Dhania Putri Sarahtika

<>

NOTE : All photographs, news, editorials, opinions, information, data, others have been taken from the Internet ..aseanews.net |

[email protected] |

For comments, Email to :

D’Equalizer | [email protected] | Contributor