OP-ED: Lead by example

EDITORIAL

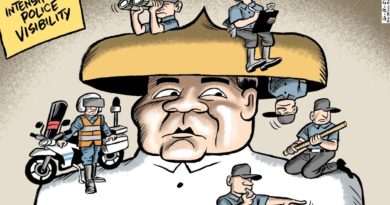

Lead by example

.As Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha declared fighting corruption in the public sector as one of his government’s policies in parliament yesterday, he and his cabinet ministers must not just live up to this promise, but also lead by example. Submitting their asset and debt declaration to the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC) in a transparent and honest manner is the first step for them to prove that this is not just an empty promise.

———

Unfortunately, the assets declaration process — which could help the agency and the public keep tabs on public officials’ wealth while they are in office — may not be as transparent as it should be, as Gen Prayut and his six ministers can excuse themselves from it.

Another hurdle to transparency has something to do with how the NACC deals with any claims of “borrowed” assets — a consequence of its own ruling that cleared deputy PM Prawit Wongsuwon of any wrongdoing in the “borrowed” luxury watch scandal.

Under the 2018 anti-corruption law, cabinet members, MPs and senators have to submit a list of their assets and liabilities, which also includes their spouse and children within 60 days of assuming office.

However, on Wednesday, NACC secretary-general Worawit Sukboon delivered what seemed to be good news for Gen Prayut and his six ministers — saying they are not obliged by the law to disclose their assets and debts to the NACC. The law, he said, exempts those who assumed their new positions within 30-days of leaving their former post, as this is considered by the agency as an “adjustment period”.

———

The six ministers referred to above are those whom Gen Prayut brought from his old government into his new cabinet, and include his three deputies — Gen Prawit, Wissanu Krea-ngam, and Somkid Jatusripitak. The others are Interior Minister Gen Anupong Paojinda, Foreign Minister Don Pramudwinai, and Deputy Defence Minister Chaicharn Changmongkol.

They might not have been entitled to this waiver if the former cabinet was dissolved prior to the election, and a caretaker government was formed in its place, which would make the transition period from their old to new jobs longer than a month.

But the military regime-sponsored constitution dictated that the military government stay on until a new government was formed. This freed his cabinet from the responsibility of assuming a caretaker role similar to what an elected government would do. These rules pave the way for the seven men to keep their wealth records away from public scrutiny until the government completes its term. This is not what is called “transparency”.

The seven men can rise above this by submitting their asset and debt declarations of their own free will, even if the law does not require them to do so. Doing so sends a message that the government is serious about its anti-corruption policy.

Meanwhile, the NACC — whose commissioners were appointed by Gen Prayut’s lawmakers — will face the difficult task of scrutinising the assets of the new cabinet members, MPs and senators.

The NACC’s ruling on the luxury watch probe sets the wrong precedent, as it shows the agency is weak for buying Gen Prawit’s claim that he had borrowed the watch from a deceased friend, effectively clearing him from wealth concealment allegations.

This sets a low bar for the handling of similar claims, as others can exploit this tactic to get away with concealing wealth by simply labelling them as “borrowed” assets. Making anti-graft policies is easy. Executing them is always challenging, especially when policymakers have done little to lead by example.

EDITORIAL

BANGKOK POST

———

.

All photographs, news, editorials, opinions, information, data, others have been taken from the Internet ..aseanews.net | [email protected]

.|.For comments, Email to :D’Equalizer | [email protected] | Contributor