Column | Thinking Aloud : The politics of dominance: Don’t take it to the limit | The Straits Times

An overly dominant ruling party faces dangers such as resistance to change and complacency

German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s victory in the recent elections made headlines around the world because her party’s winning margin was much reduced due to the gains of the right-wing Alternative for Germany (AfD) party.

For Singaporeans though, the more peculiar feature of the result might be that her party won only 33 per cent of the votes and would need a coalition with others to form the government. That has been a hallmark of German politics for decades. Yet, despite not winning a majority, Chancellor Merkel is now into her fourth term in office and is widely regarded as the leader of the Western world, after United States President Donald Trump was unofficially stripped of the title because of his inward-looking “America First” policy. Under her leadership, Germany has strengthened its position as one of the strongest economies in the world and demonstrated forthright stewardship of the troubled European Union.

Question: How has the country been able to achieve all these despite its politics of coalition government? Or, is its ability to accommodate a wide range of views one of the secrets to its strength?

.

I do not know the answer but whatever it is, it is a world apart from Singapore, where the defining characteristic has been the dominant position of the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP), which has won every general election since independence in 1965. So overwhelming has its hold been that there has not been a single year when the opposition held more than 10 per cent of the seats and many in which it held none.

Singapore has done exceptionally well during these years of PAP dominance. The economy has grown, per capita income is one of the highest in the world, and the city has been transformed beyond recognition. There are many reasons for its success but political stability has often been touted as a major factor.

Indeed, the Government has repeatedly stressed that because of Singapore’s small size and limited talent pool, it cannot afford to have the revolving-door politics seen in many Western democracies, with parties taking turns at the helm, or worse, suffer a coalition government.

Singaporeans, by and large, understand the benefits of a strong government: the ability to plan for the long term, and to be able to implement policies quickly without politics getting in the way.

In contrast, the Germans would recoil at the thought of having one party dominate the country, having learnt their painful lesson in the brutal years leading to World War II when the Nazi Party led by Adolf Hitler muscled its way to power.

To each his own then, and never the twain shall meet?

Every country has to decide which system works best for it, shaped by its own history and the unique circumstances of its people and culture. There is no universal model.

Every country has to decide which system works best for it, shaped by its own history and the unique circumstances of its people and culture. There is no universal model. But there are dangers when any one system is taken to extremes.

But there are dangers when any one system is taken to extremes.

In Germany, seats are allocated by proportional representation, which encourages multi-party democracy and works against a dominant party system. This has helped extreme right-wing parties such as the AfD gain a foothold, the first time in 60 years they have been able to do so. Analysts predict a rough time ahead as fringe parties enter the fray with their divisive politics.

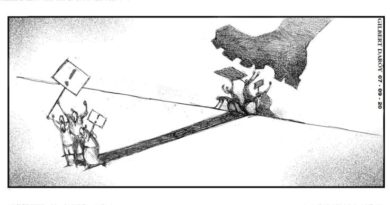

In Singapore, danger comes from the other end of the spectrum, from an overly dominant government. It can lead to complacency when leaders lose touch with the ground and ordinary people’s concerns. Without a strong opposition and other influential voices outside the party, groupthink can set in.

The PAP suffered from some of this in the years leading to the 2011 General Election (GE), when it failed to address issues such as rising property prices, overcrowded MRT trains and an overly liberal immigration policy leading to a large influx of foreign workers. It was accused of being elitist in its approach.

To its credit, it acknowledged its weaknesses after suffering one of its worst setbacks in the GE, tackled the problems, and reaped the benefits in the 2015 GE.

Now, there are renewed concerns it is exercising its dominant powers by introducing the reserved presidency despite unhappiness among the people. Its overwhelming electoral victory in 2015 has no doubt made it more assured in dealing with these politically sensitive issues.

There is a familiar cycle to the politics of dominance, with the ruling party testing the limits of its power and recalibrating it at every election depending on how well it performs.

But it has to watch that it does not overplay its card because the Singapore political landscape is a flat one and can be swayed by one major nationwide issue, such as the reserved presidency. There might still be a political reckoning to come in the next election.

Besides complacency, there are two other dangers of an overly dominant government.

One is the blurring of lines between the party and the state. This is a pertinent risk in Singapore because the ruling party has been in power for so long, the public service has known no other political master. Public servants are supposed to be politically neutral in theory, but in practice it can be difficult to draw the line.

For example, opposition politicians have long complained that the People’s Association (PA) discriminates against them in not appointing opposition Members of Parliament as grassroots advisers even though they have been duly elected by the people. The Government has argued that the PA exists to explain and promote government programmes, a role it does not expect the opposition to support.

In reality, any ruling party anywhere will want to maximise the advantage it enjoys in incumbency. That’s only natural, and the PAP, because of its longevity, knows this better than anyone.

But if overdone, it risks undermining the integrity of public institutions and public confidence in them.

This would have serious consequences for Singapore because its public service is among the best in the world, with a reputation painstakingly built over the years.

The other danger an overly dominant ruling party faces is resistance to change even when circumstances require it. I do not mean adjustments of government policies but more fundamental changes to the party’s internal workings, such as who and how it attracts new members, how it selects its leaders, and what its approach is to alternative views.

The tendency of most dominant systems is to preserve the status quo because of inertia and vested interests. Can change come voluntarily from within, or will it be forced by external circumstances? The record of most dominant parties around the world, including the Liberal Democratic Party in Japan, Umno in Malaysia and the African National Congress in South Africa, favours the latter. The PAP, being politically stronger than any of these parties, might yet prove the exception.

None of these potential risks will make Singaporeans desire coalition government or Germans embrace a dominant-party system. But both would do well to recognise the dangers of taking any one form to the extreme.

• The writer is also a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.

<>

NOTE : All photographs, news, editorials, opinions, information, data, others have been taken from the Internet ..aseanews.net | [email protected] |

For comments, Email to :

D’Equalizer | [email protected] | Contributor