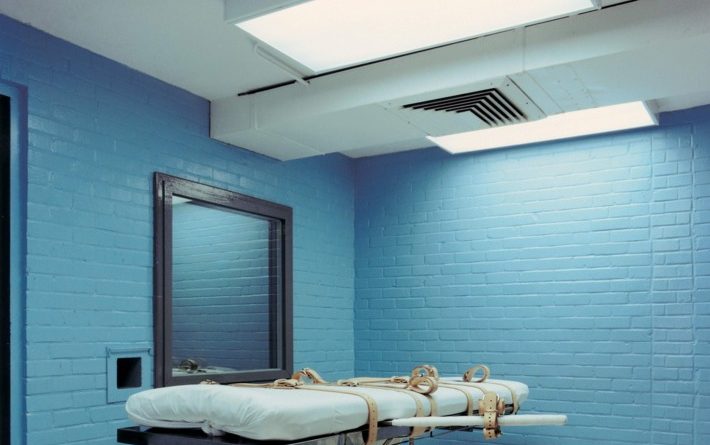

OP ED COLUMN: OPINION ON PAGE ONE – Will conflict intensify on capital punishment?

CONFLICTED Church-State relations could soon intensify in countries like the Philippines after Pope Francis declared a radical change in Church teaching on capital punishment. Through a letter from the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith, the Pope announced that instead of the present teaching which allows capital punishment for certain crimes, the Catechism of the Catholic Church will now declare: “The Church teaches, in the light of the Gospel, that the death penalty is inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person.”

The Philippines, which is predominantly Catholic, abolished the death penalty in 2006. But the government favors its revival, and its murderous anti-drug campaign has already killed thousands of drug suspects without due process since July 2016. If President Rodrigo Duterte follows the new teaching, the killings will all have to end. But he has cursed the Church, Church leaders, foreign dignitaries and human rights workers for criticizing his “extrajudicial killings.”

DU30 will most likely go ballistic, should the Pope, any bishop, priest or layman invoke the new teaching against the killings. But the strongest reaction is likely to come not from rightest governments and strongmen, but from within the Church itself. Because the new teaching seeks to reverse the Church’s clear and consistent teaching on capital punishment for the past 2,000 years, it has provoked serious doubts and objections among theologians.

In 2001, Cardinal Avery Dulles, a Jesuit scholar, wrote, “The Catholic magisterium does not, and never has advocated, unqualified abolition of the death penalty. I know of no official statement from popes or bishops, whether in the past or in the present, that denies the right of the state to execute offenders at least in certain extreme cases.”

The 1992 Catechism of the Catholic Church by Pope St. John Paul II concedes to legitimate public authority the right and duty to “punish malefactors by means of penalties commensurate with the gravity of the crime, not excluding, in cases of extreme gravity, the death penalty. The primary effect of punishment is to redress the disorder caused by the offense. If bloodless means are sufficient to defend human lives against an aggressor and to protect public order and the safety of persons, public authority should limit itself to such means because they better correspond to the concrete conditions of the common good and are more in conformity with the dignity of the human person.”

Inadmissible to whom?

The letter from the CDF makes capital punishment even in extreme cases “inadmissible.”

Michael Pakaluk, professor of ethics at the Catholic University of America, finds that word strange. In a current article in First Things, the most influential American journal on religion and public life, he writes:

“The word appears nowhere else in the Catechism,” he observes. “It is almost a solecism in moral theology. We speak of inadmissibility in legal, logical or interpretive context: inadmissible evidence, an inadmissible premise, an inadmissible construction. That is, the category of the inadmissible brings in some notion of will.

“Thus, ‘the death penalty is inadmissible’ invites the question, By whom? On whose will? The language smacks of raw judicial power, portending ominously that the Catechism will conform to the will of successive popes. Much as the US Supreme Court has been politicized, the category of the inadmissible risks politicizing the papacy.”

In Pope Francis and Capital Punishment, Edward Feser takes a critical look at the Pope’s new teaching, also in First Things. Feser is co-author with Joseph Bessette of the critically acclaimed, By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment. He writes:

“… the Church has always taught, clearly and consistently, that the death penalty is in principle consistent with natural law and the Gospel. This is taught throughout scripture—from Genesis 9 to Romans 12 and many points in between—and the Church maintains that scripture cannot teach moral error. It was taught by the Fathers of the Church, including those Fathers who opposed the application of capital punishment in practice. It was taught by the Doctors of the Church, including St. Thomas Aquinas, the Church’s greatest theologian; St. Alphonsus Liguori, the greatest moral theologian; and St. Robert Bellarmine who, more than any other Doctor, illuminated how Christ’s teaching applies to modern political circumstances.

Clear and consistent teaching

“It was clearly and consistently taught by the popes up to and including Pope Benedict XVI. That Christians in principle legitimately resort to the death penalty is taught by the Roman Catechism promulgated by Pope St. Pius V, the Catechism of Christian Doctrine promulgated by Pope St. Pius X, and the 1992 and 1997 versions of the most recent Catechism promulgated by Pope St. John Paul II — the last despite the fact that John Paul was famously opposed to applying capital punishment in practice. Pope St. Innocent I and Pope Innocent III taught that acceptance of the legitimacy in principle of capital punishment is a requirement of Catholic orthodoxy. Pope Pius XII explicitly endorsed the death penalty on several occasions…

“Joseph Bessette and I document this traditional teaching at length in our recent book. For reasons I have set out in a more recent article, the traditional teaching clearly meets the criteria for an infallible and irreformable teaching of the Church’s ordinary Magisterium. It is no surprise that so many popes have been careful to uphold it, nor that Bellarmine judged it ‘heretical’ to maintain that Christians cannot in theory apply capital punishment.

“So, has Pope Francis now contradicted this teaching? On the one hand, the letter issued by the CDF announcing the change asserts that it constitutes ‘an authoritative development of doctrine that is not in contradiction with the prior teachings of the Magisterium.’ Nor does the new language introduced into the catechism clearly and explicitly state that the death penalty is intrinsically contrary to either natural law or the Gospel.

“On the other hand, the Catechism as John Paul left it had already taken the doctrinal considerations as far as they could be taken in an abolitionist direction, consistent with past teaching. That is why, when holding that the cases in which capital punishment is called for are ‘very rare, if not practically non-existent,’John Paul’s Catechism appeals to prudential considerations concerning what is strictly necessary in order to protect society.

“Pope Francis, by contrast, wants the Catechism to teach that capital punishment ought never to be used (rather than ‘very rarely’ used), and he justifies this change not on prudential grounds but ‘so as to better reflect the development of the doctrine on this point.’ The implication is that Pope Francis thinks that considerations of doctrine or principle rule out the use of capital punishment in an absolute way.

Contrary to natural law?

“Moreover, to say, as the pope does, that the death penalty conflicts with the ‘inviolability and dignity of the person’ insinuates that the practice is intrinsically contrary to natural law. And to say, as the pope does, that ‘the light of the Gospel’ rules out capital punishment insinuates that it is intrinsically contrary to Christian morality.

“To say either of these things is to contradict past teaching. Nor does the letter from the CDF explain how the new teaching can be made consistent with the teaching of scripture, the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, and previous popes. Merely asserting that the new language ‘develops’ rather than ‘contradicts’ past teaching does not make it so…

“An irony is that John Paul’s Catechism was issued to clarify matters of doctrine, and finally put a halt to post-Vatican II speculation that Catholic teaching was open to endless revision. Yet now, we have had two revisions to the Catechism’s own teaching on capital punishment—one in 1997, under John Paul himself, and another under Francis…

Wrong for 2,000 years?

“If capital punishment is wrong in principle, then the Church has for two millenniums consistently taught grave moral error and badly misinterpreted scripture. And if the Church has been so wrong for so long about something so serious, then there is no teaching that might not be reversed, with the reversal justified by the stipulation that it be called a ‘development’ rather than a contradiction. A reversal on capital punishment is the thin end of a wedge that, if pushed through, could sunder Catholic doctrine from its past — and thus give the lie to the claim that the Church has preserved the Deposit of the Faith whole and undefiled.

“Not only does this reversal undermine the capability of every previous pope, it undermines the credibility of Pope Francis himself. For if Pope St. Innocent I, Pope Innocent III, Pope St. Pius V, Pope St. Pius X, Pope Pius XII, Pope St. John Paul II, and many other popes could get all things so badly wrong, why should we believe Pope Francis has somehow finally gotten things right?

“One does not need to support capital punishment to worry that Pope Francis may have gone too far. Cardinal Avery Dulles, who was personally opposed to the practical use of capital punishment, still insisted that ‘the reversal of a doctrine as well established as the legitimacy of capital punishment would raise serious problems regarding the credibility of the magisterium.’ Archbishop Charles Chaput, who is likewise opposed to applying the death penalty in practice has nevertheless acknowledged:

‘The death penalty is not intrinsically evil. Both Scripture and Christian tradition acknowledge the legitimacy of capital punishment under certain circumstances. The Church cannot repudiate that without repudiating her own identity.’

‘If Pope Francis is claiming that capital punishment is intrinsically evil, then either scripture, the Fathers and Doctors of the Church and all previous popes were wrong — or Pope Francis is. There is no third alternative. Nor is there any doubt about who would be wrong in that case. The Church has always acknowledged that popes can make doctrinal errors when not speaking ex cathedra—Pope Honorius I and Pope John XXII being the best-known examples of popes who actually did so.

“The Church also explicitly teaches that the faithful may, and sometimes should, openly and respectfully criticize popes when they do teach error. The 1990 CDF document Donum Veritatis sets out norms governing the legitimate criticism of magisterial documents that exhibit ‘deficiencies.’ It would seem that Catholic theologians are now in a situation that calls for application of these norms.”

[email protected] All photographs, news, editorials, opinions, information, data, others have been taken from the Internet ..aseanews.net | [email protected] |.For comments, Email to :D’Equalizer | [email protected] | Contributor

All photographs, news, editorials, opinions, information, data, others have been taken from the Internet ..aseanews.net | [email protected] |.For comments, Email to :D’Equalizer | [email protected] | Contributor