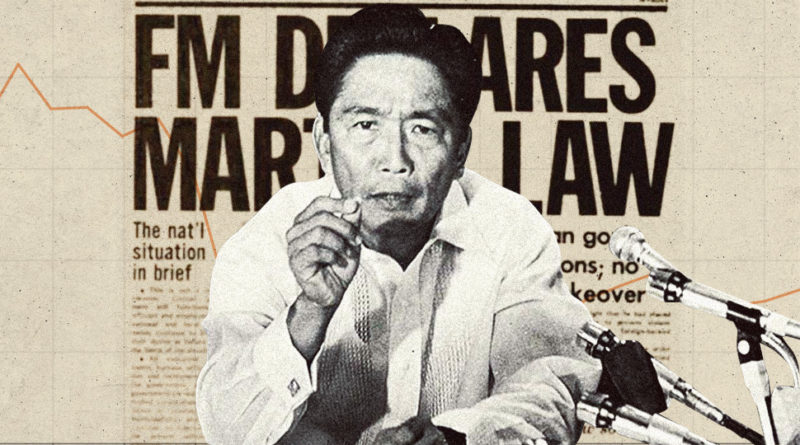

MARCOS MARTIAL LAW | How Did the Declaration of Martial Law in 1972 Impact the Economy?

A quick look at the impact of authoritarian rule on infrastructure, debt, GDP, inflation and the stock market.

To family and supporters of the former President Ferdinand Marcos, his declaration of martial law on September 23, 1972 (though he antedated the official document to September 21) remains a watershed event that ushered in what some of them consider to be the “golden age” of the Philippines.

>

Ad by:

Memento Maxima Digital Marketing

@[email protected]

SPACE RESERVE FOR ADVERTISEMENT

.

For example, his son, the former Senator and now President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., wrote a Facebook post on September 21, 2012: “In 1973, our GDP growth rate stood at 8.9 percent that took a dip the following year to below five percent as a result of the oil embargo. Subsequently, it stayed above five percent through all the succeeding years up to 1980 with a high of 8.8 percent in ’76.” He acknowledged that GDP suffered a “negative growth” in 1984 but blamed it largely on “Senator Aquino’s assassination in August of 1983 and what followed.”

Other Marcos supporters, arguing along the same line, point out that the former president embarked on an unprecedented level of infrastructure spending, building roads, bridges and other civil works throughout the country. Prices of consumer goods were supposedly more stable shortly after martial law because of Marcos’ Kadiwa rolling stores.

But a broader look at the entire authoritarian period from 1972 to early 1986 (Marcos supposedly lifted martial law in 1981 but retained the right to enact laws alongside parliament), reveals an entirely different picture.

While it’s true that infrastructure spending surged in the mid-1970s (as indicated by gross fixed capital formation), this was accompanied by soaring external debt, which proved to be the bane of the economy when the country can no longer pay for these in the 1980s. By then, infrastructure spending plunged to its lowest levels, taking years to recover.

Economic growth followed the same pattern. It’s true, as former Senator Marcos claims, that GDP growth surged to record levels in 1973 and 1976. However, the plunge to the worst-ever economic contraction in 1984 and 1985 wasn’t just caused by the Aquino assassination but, more importantly, by the government’s inability to pay its mounting foreign debts.

GDP per capita (a rough indicator of average income per person) started falling in 1983 and only recovered in the early 2000s, which means it took the Philippines two decades to get back on track. By then, the Philippines already lagged way behind its neighbors.

The same story is evident with inflation, which fell shortly after martial law was declared. It dropped from 14.4 percent in September 1972 to only 4.8 percent in December that year. However, by September 1984, inflation hit 62.8 percent, the highest since 1958.

Emmanuel S. De Dios, a former dean at the UP School of Economics, pointed out that the reason for the early economic gains of the martial law regime and the severe contraction that followed it in the early 1980s are one and the same: excessive foreign borrowings.

“The reason for the dismal performance under martial law is well understood. The economy suffered its worst post-war recession under the Marcos regime because of the huge debt hole it had dug, from which it could not get out,” explained Emmanuel S. De Dios in a BusinessWorld column in 2015.

>

Ads by:

Memento Maxima Digital Marketing

@[email protected]

SPACE RESERVE FOR ADVERTISEMENT